Claire Macdonald, Grants Writer and Editor at Agence de Médecine Préventive

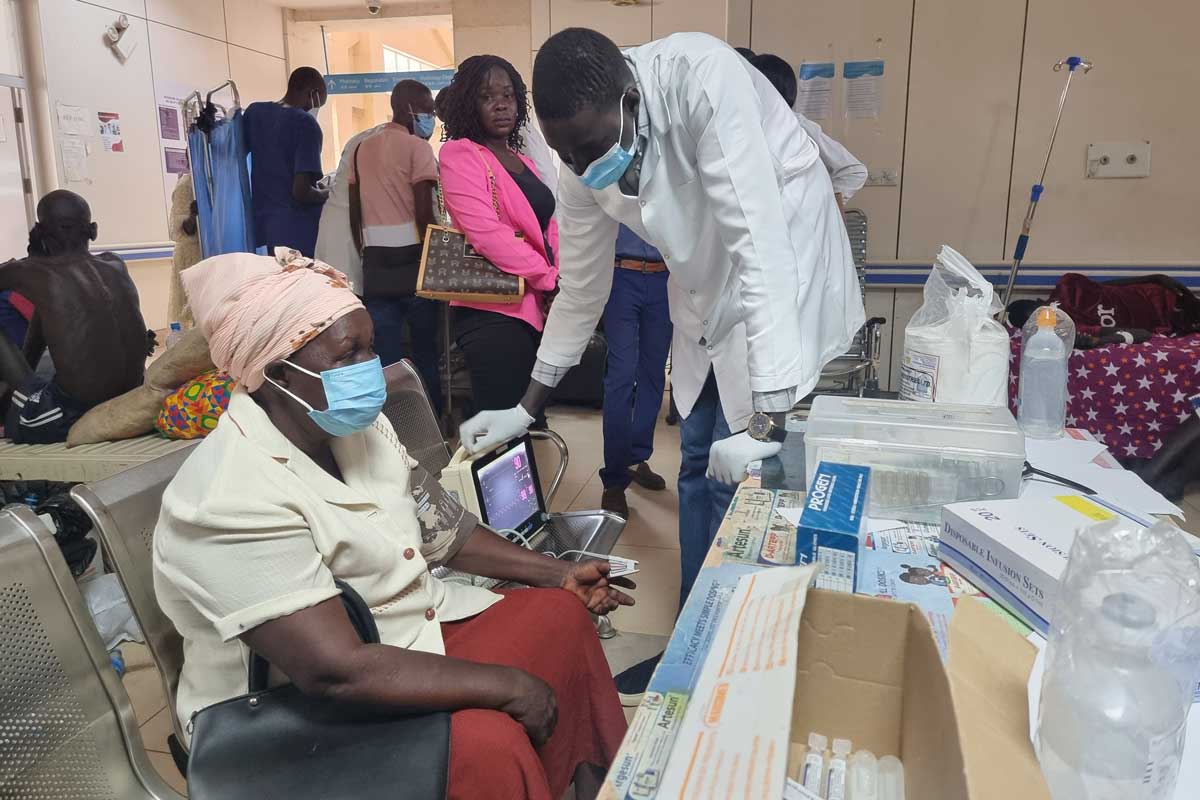

Access to clean water and vaccination in lower income countries (like Malawi, pictured) is vital to prevent cholera. Photo: Christel Saussier.

Preventing and controlling outbreaks is by no means an exact science. It was hard to avoid this conclusion in 2015, as Ebola spread through five African countries, reached Europe and the US, and killed more than 11,000 people. The West African outbreak showed how quickly a disease that had been relegated to ‘small outbreaks’ could spin out of control.

Ebola is not alone in this; cholera also causes outbreaks with devastating consequences, and it is thought to kill more than 100,000 people annually. In the past two years alone, large African cities such as Accra, Kinshasa, Goma and Dar-Es-Salaam have witnessed cholera epidemics that ravaged their communities.

Fortunately, the vulnerability of Africa’s cities has caught the attention of global stakeholders, whose desire to stay one step ahead of the next serious epidemic is also at the core of French NGO Agence de Médecine Préventive (AMP) and its international and local partners. Together, they have been working since 2010 to prevent outbreaks through the African Cholera Surveillance Network consortium (Africhol, for short).

Thanks to a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the multi-partner consortium supports a cholera prevention network in 11 African countries. The bedrock of the project is surveillance, which remains the key for detecting cholera outbreaks, controlling the disease, and reducing deaths. It is now a proven working model that could even be replicated throughout the world for other contagious diseases.

Cholera is closely linked to poor sanitation, a lack of clean water and inadequate infrastructure. Typical at-risk areas include peri-urban slums, as well as camps for internally displaced persons or refugees. Urbanization, the uncontrolled sprawl of cities in low-income countries together with the stream of refugees fleeing into unsanitary camps creates ideal conditions for contagious diseases to spread quickly. Global warming is also thought to encourage the disease, which means cholera remains a worldwide threat.

The nature of the disease makes it difficult to control. It does not distinguish between adults and children, and can kill within hours, leaving little time for diagnosis, treatment, or reporting. Although it’s easy to treat, many people still die, especially in remote areas where even basic health care can be difficult to access.

The main aim of Africhol is to inform prevention strategies, such as immunization, across Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Kenya, Mozambique, Nigeria, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. These strategies enable public health authorities to target measures such as immunization by identifying cholera hotspots, community behaviors that contribute to spreading cholera, and high risk populations. This can make immunization campaigns more effective, and not just a shot in the dark.

A girl receives a cholera vaccine in Cameroon. Photo: Gavi/2015/Athanas Makundi.

The impetus behind the project was the blind nature of intervention in cholera epidemics. Nearly 200,000 cases and more than 1,000 deaths were reported to the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2015, but these numbers are thought to be misleading due to underreporting and inadequate national surveillance systems, as well as countries’ fear of trade and travel sanctions. The true global cholera burden is estimated to be one to four million cases and up to 150,000 deaths annually.

The way cases are reported has also prevented a clear picture of the disease. Methods for recognizing and classifying cholera cases varies between, and even within countries, with delays and incomplete reporting between district and national levels.

Africhol targeted these problems by helping participating countries to expand their laboratory capacities for routine confirmation of suspected cholera cases, while also working within existing national surveillance systems. A common protocol for all participating countries ensures that the data collected is comparable between countries.

As a result, we have a wealth of new information on at-risk populations and geographical hotspots. This has provided participating countries and global stakeholders with a new understanding of cholera in Africa and the basis for innovative ways to fight the disease. These information gathering systems are also paving the way for future work on cholera and other contagious diseases, and have made a decisive impact on the public-health systems of the countries involved.

Like most battlefields, however, conditions constantly change and up to date information is essential if strategies are to remain effective and antibiotic treatments to stay current. As new epidemic threats loom over Africa, the consortium remains a vital information and communication hub, where members have a common place to share data, launch initiatives, and develop common tools and protocols for use on and beyond cholera.

The Africhol consortium demonstrates the importance of disease surveillance and the power of collaboration to create the essential tool of unified foresight for all kinds of threats. With this tool in place, the consortium can and should provide a platform for the identification, prioritization and implementation of effective prevention measures against epidemic diseases in some of the world’s most vulnerable populations.