Battling malaria, South Sudan anticipates roll-out of life-saving vaccines

As South Sudan prepares to deploy a new weapon in its fight against malaria, the R21 vaccine, Winnie Cirino surveys the parasitic disease’s foothold.

- 16 July 2024

- 7 min read

- by Winnie Cirino

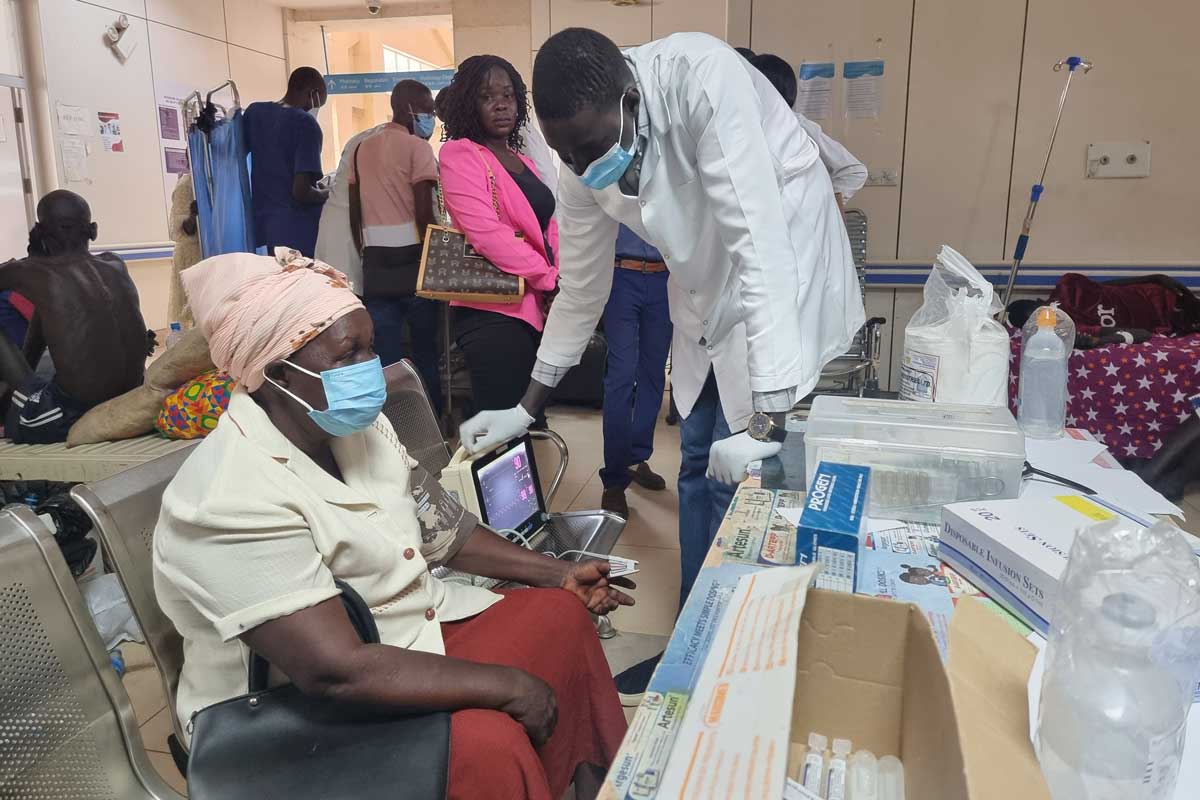

“Almost 70% of the patients we treat in the hospital nowadays are mainly malaria victims,” says Dr Jak Gatluak, head of Accident and Emergency at Juba Teaching Hospital in South Sudan. “If we have ten cases [to see], you will find like seven to eight cases are malaria.”

South Sudan has one of the highest malaria incidences in the world, recording an estimated 7,680 cases and 18 deaths each day, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). The mosquito-borne parasitic infection is also the leading cause of death among children in the country, with 2.8 million paediatric cases and 6,680 deaths recorded in 2022 alone.

“The thought of a future where I don’t have to endure the agony of watching my child suffer from malaria is profoundly reassuring. […] I would not hesitate for a second to have my child vaccinated once these vaccines become available.”

- Claire Achayo, mother

Though malaria is a threat year-round, the view from the frontlines is especially bleak during the rainy season, which runs from May to November. "We have very little number of anti-malaria drugs and the non-government organisation that used to support us with the drugs stopped," Gatluak stresses. "The private hospitals sell theirs expensively. People are not taking anti-malaria drugs, which can contribute to more cases of malaria."

There are other helpful tools, like treated bed-nets, which researchers continue to recommend as a crucial line of defence. But Dr Gatluak expresses hopes that the arrival of the R21 malaria vaccine, due to begin rolling out later this month, might change the picture he is confronted with daily. The government often spends a lot of money purchasing the antimalaria drugs and the malaria testing kits.

“We are very happy to try it,” Gatluak says. “[The vaccines] will reduce the disability and mortality rates that are happening every year among under-fives and pregnant mothers.”

“Helplessness and fear” in the throes of illness

Malaria takes a cruel toll even on its survivors. Claire Achayo, a mother with a one-year-old baby who has suffered from malaria multiple times, shares tells VaccinesWork, “Watching my son suffer was heart-wrenching. He was too young to understand what was happening to him, and I felt helpless as a parent. His cries of discomfort, and the fever that seemed relentless, kept me up at night, praying for his swift recovery,” Achayo narrates. “I tell you, the helplessness and fear that gripped me during that time were indescribable.”

Her experience has made her eager to vaccinate her child with the malaria vaccine. “The thought of a future where I don’t have to endure the agony of watching my child suffer from malaria is profoundly reassuring. And I know the malaria vaccine is a game-changer, because I believe they provide a certain layer of protection that could save countless lives and spare many from the suffering that my son and I have gone through,” Achayo explains.

Coming from a country with high malaria prevalence, especially among children, Achayo sees the arrival of the malaria vaccines to South Sudan as a blessing for mothers like herself.

“I would not hesitate for a second to have my child vaccinated once these vaccines become available. Knowing that there is a way to prevent this dreadful disease gives me hope for a healthier future for my son and all the children in our community.”

Susan Yeno, a mother of two children, also applauds the introduction of the malaria vaccine. “I am one person who has ensured that my two children are fully vaccinated, and considering that South Sudan has a long way to go with eliminating malaria, I am happy to know that malaria vaccines are being introduced in the country. I believe this will help us parents from the deadly disease malaria, just like the other vaccines.”

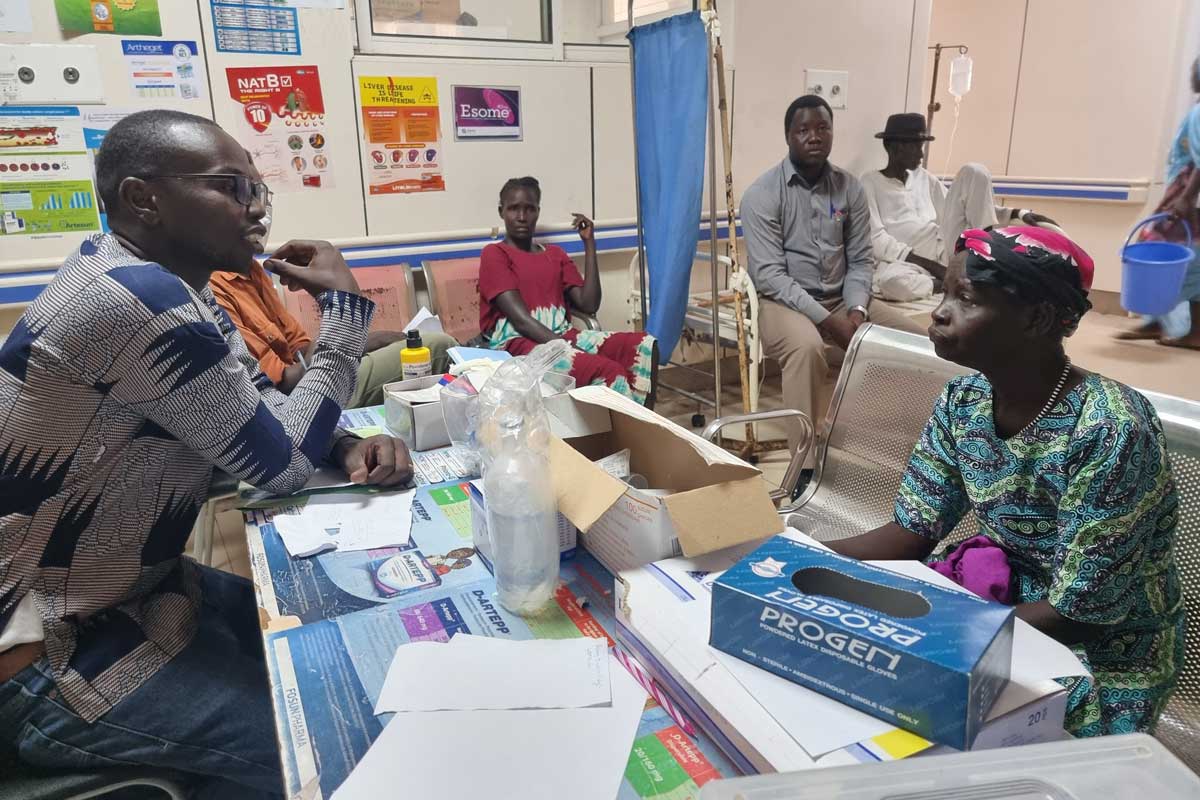

A sky-high burden

Dr Joseph Panyuan Puok, Director of Malaria Programs at the Ministry of Health, highlights the pervasive nature of malaria in South Sudan as whole. “The data we have shows that 60% of consultations in any facility's Outpatient Department are primarily for malaria, and it is particularly deadly among children under five.” He further notes that of those admitted to inpatient wards, 42% battle malaria. “The mortality in all cases for those who die by all diseases, 30% of them are from malaria also,” he adds.

“I am happy to know that malaria vaccines are being introduced in the country. I believe this will help us parents from the deadly disease malaria, just like the other vaccines.”

- Susan Yeno, mother

Low rates of health education in parts of the country give the disease cover to spread, Dr Puok explains. “Some people still believe that if a child plays in the sun he will get malaria, not knowing that the disease is caused by a parasite that is transmitted by a mosquito,” he states.

The lack of medical attention-seeking behaviour further exacerbates the problem. People often delay seeking treatment or fail to complete their medication courses. “When we use Artesunate/amodiaquine, they have some severe side effects such as nausea, salivation, and body discomfort. When symptoms subside, some people stop the treatment,” Dr Puok notes, describing this as a very bad habit.

Malnutrition is another significant issue in South Sudan, especially among children and pregnant mothers. Dr Puok explains that malnutrition causes anaemia, which complicates malaria cases. “Pregnant mothers often get miscarriages, because severe malaria will always affect the child inside the mother,” he says.

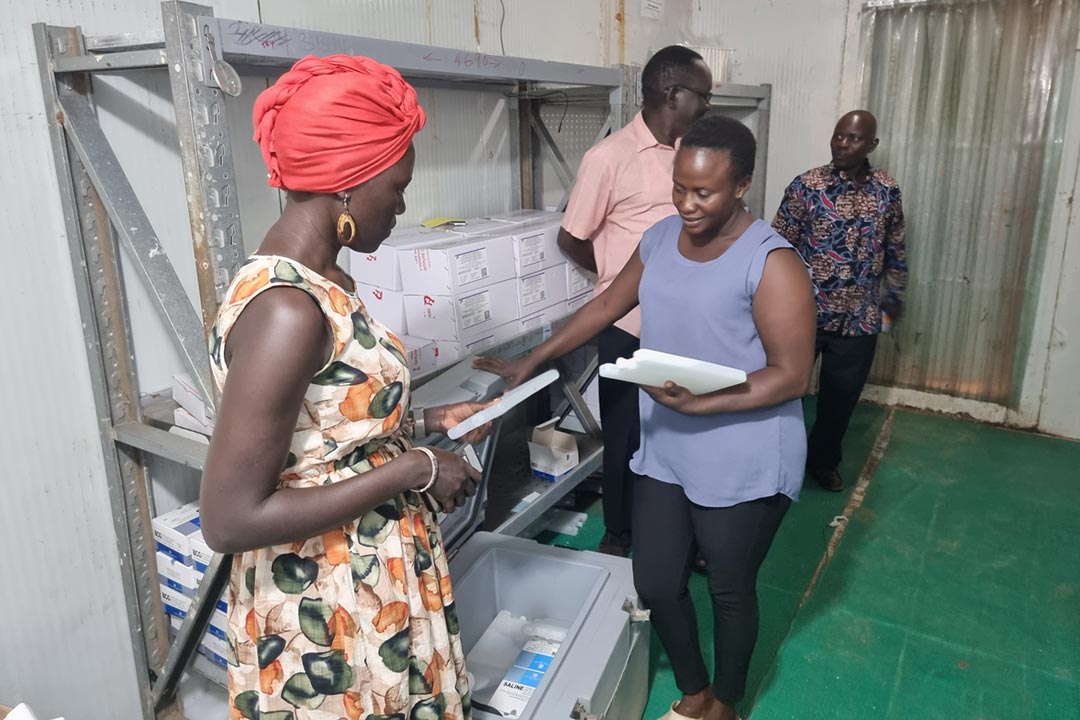

In many remote areas of South Sudan, there are no private health facilities, leaving residents dependent on government hospitals, which sometimes experience stock-outs of essential medicines. That means no medicines, says Dr Puok. “Somebody will come, and you will diagnose, it is malaria, you tell him to go and buy. They may not find the medicine to buy, or even the drug may be there, but the storage conditions may not favour the potency, as each drug has a certain temperature they cannot exceed.”

“A child will be vaccinated routinely – grab the chance as this is an opportunity that has never been before.”

- Dr Joseph Panyuan Puok, Director of Malaria Programs at the Ministry of Health

Battle stations

The Ministry of Health has implemented several interventions to combat malaria, including creating more awareness about the causes and prevention of the disease. They have supported communities with treated mosquito nets, although some people misuse them for fishing, while others complain that the nets are itchy and too transparent, interfering with their privacy.

However, the R21 malaria vaccine roll-out marks the addition of a new weapon to the country’s antimalarial arsenal. Dr Puok is radiant with optimism about the potential impact of this development. “I am 100% sure; no child will develop severe malaria when they are vaccinated. This means no child will die from malaria,” he asserts. He encourages parents to take advantage of this opportunity, stating, “A child will be vaccinated routinely – grab the chance as this is an opportunity that has never been before.”

While the four-dose R21 vaccine is scheduled for use only in young children, adult residents of Juba sounded an upbeat note, as this very first vaccine roll-out seemed to signal the start of a new chapter in the country’s relationship with the parasitic killer.

Have you read?

Emmanuel Nichola recalled a 2023 tussle with the disease. “I couldn’t go to work. After a week-long stay home because of the sickness, I had a lot of work piled up at my desk, which I had to catch up with,” he says. With the introduction of the malaria vaccine, Nichola expresses hope that it will reduce severe malaria. “This vaccine is good because there is a lot of malaria and typhoid here. And you know Juba is dirty and dirt is a breeding place for mosquitoes which will be too many and that causes malaria. I hope the vaccine will indeed reduce malaria cases.”

Jane Dawa, another Juba resident who owns a small restaurant, was sick in May. “I had to close my restaurant for some two days to recover,” she narrates. “What I can say is that I am happy about the malaria vaccines. That will keep us strong.”

More from Winnie Cirino

Recommended for you