Everything you need to know about the brain-eating amoeba that’s killed three children in Kerala

Although deaths from amoebic meningoencephalitis are rare, they could become more common because of climate change.

- 18 July 2024

- 5 min read

- by Linda Geddes

After three children in Kerala, India, died, and a fourth was infected, the "brain-eating amoeba" Naegleria fowleri is back in the spotlight.

Each year, sporadic cases are reported in hot and humid areas of the world, and they are frequently fatal. Usually, these infections are in people who have been swimming in lakes, rivers or underchlorinated pools, although clusters of infections have also been linked to contaminated water supplies. For now, infection with N. fowleri (Naegleria) is rare, but scientists are concerned that climate change could cause this, and other pathogenic amoebas, to expand their ranges towards the poles, and bring more people into contact with infected water.

Although primary amoebic meningoencephalitis is extremely rare, with just 381 cases reported in the medical literature up until 2018, it is also extremely deadly: of these 381 cases, just seven individuals survived.

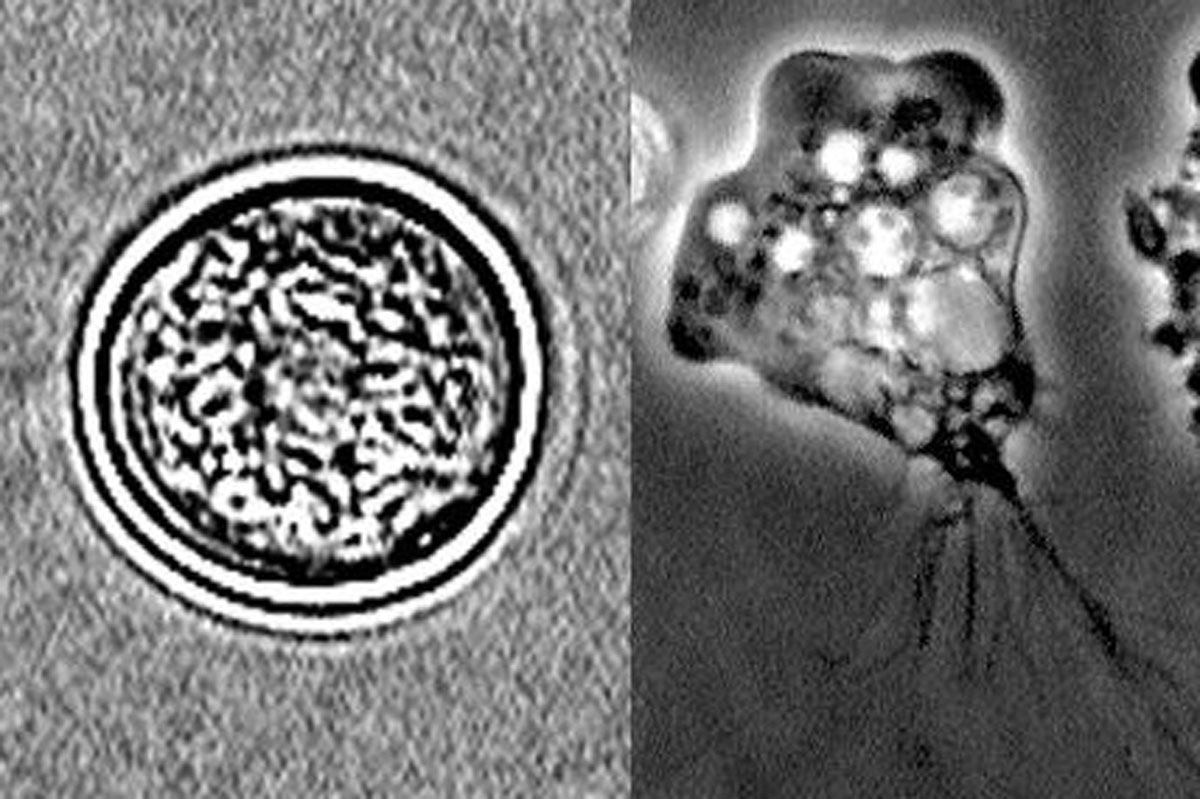

Brain-eating amoeba

Free-living amoebas are tiny single-celled organisms that mostly live in fresh water. There are four main types that can cause human disease, of which N. fowleri (Naegleria) and Acanthamoeba species are particularly problematic. They can enter the body through the nose, and travel to the brain, where they start to destroy tissue and cause the brain to swell, triggering a condition called primary amoebic meningoencephalitis (PAM). Naegleria can also survive in soil by forming dormant ‘cysts’, and infections have been linked to the inhalation of contaminated dust.

Although PAM is extremely rare, with just 381 cases reported in the medical literature up until 2018, it is also extremely deadly: of these 381 cases, just seven individuals survived. It is also likely that many cases go unreported, as medical awareness of the condition is low and symptoms mimic those of bacterial and viral meningitis – infections that occur in some of the same regions where Naegleria thrives.

Patients usually report swimming, diving, bathing, or playing in warm fresh water over the previous nine days, although some recent cases in Pakistan and the US – countries with the highest number of cases each year – have been linked to nasal cleansing with a neti pot or similar device containing contaminated tap water.

Symptoms include fever, severe headache, nausea, vomiting, sensitivity to light, seizures and an altered mental state. Because the condition is difficult to diagnose and progresses very quickly, identifying effective treatments has been very different. In the USA, there have been five documented survivors, who were treated with a combination of antibiotics, anti-fungals and steroid drugs.

Recent cases

So far, three children in Kerala have died since May: a five-year-old girl from Malappuram, a 13-year-old girl from Kannur, and a 14-year-old boy from Kozhikode. A 14-year-old boy from Payyoli is also reportedly receiving treatment for the infection. During 2024, unconnected infections have also been reported in Pakistan, Israel and Wyoming, US. Naegleria was also detected at a popular freshwater swimming spot in Western Australia earlier this year, prompting its closure. Local officials believe unusually high temperatures may have bolstered amoeba numbers.

Warm waters

Historically, Naegleria infections have largely been restricted to warm countries, especially areas where average annual temperatures lie between 15°C and 18° C. Increasingly though, infections are being reported in cooler areas, such as the northern US state of Minnesota. The amoeba was also recently detected at wastewater treatment plants in parts of the UK, although this was before the water had been treated.

According to a recent review by Sutherland Maciver and colleagues at the University of Edinburgh, UK, there has been a global increase in cases over the past two decades, although whether this is due to increased awareness of the condition is unclear.

Have you read?

However, they and other scientists are concerned that such infections could become more common because of climate change. Naegleria thrives in warm waters and can tolerate temperatures of up to 46°C, making it well-suited to spread as countries grow hotter. “Many countries are already recording extreme temperatures and many people are seeking relief from the heat by immersing themselves in water that is often very warm and polluted by coliforms [gut bacteria], perfect conditions for the growth of N. fowleri,” Maciver said.

“People in some of the same areas practise cleansing rituals in which water is forced through the [nasal passages] by specialised neti pot devices or other means. This is believed to be the cause of the alarming increase in the incidence of PAM in cities such as Karachi. However, it is very likely that other cities are also experiencing silent outbreaks and that Karachi has become a known hotspot for PAM solely because of local expertise in PAM diagnoses.”

Extreme weather events such as droughts and flooding may also enhance its spread, by concentrating the amoeba in swimming spots and encouraging the use of roof-harvested rainwater systems or artesian wells during dry weather; and moving the amoeba to new areas during flood events.

Safe bathing

Although amoebic meningoencephalitis is extremely rare, and the chances of catching it are unlikely, there are measures that people can take to reduce their risk. In the US, which typically sees fewer than ten cases of PAM each year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends holding your nose or wearing a nose clip if you are jumping or diving into fresh water; always keeping your head above water in hot springs; avoiding digging in shallow water because the amoeba is more likely to live there; and using distilled or boiled tap water when rinsing your sinuses or cleansing your nasal passages.

More from Linda Geddes

Recommended for you