Meet the global oral cholera vaccine stockpile

35 million doses of cholera vaccine rolled out worldwide last year, curbing outbreaks and saving lives. Where did they come from? Epidemiologist Allyson Russell answered our questions.

- 10 September 2024

- 12 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

Cholera loves chaos. It thrives amid conflict and natural disasters; it explodes suddenly into wildfire epidemics. We’ve known how to avoid it for well over a century, and yet, the scale and frequency of outbreaks is spiking. And even though the risk factors are evident and straightforward – cholera strikes where water and sanitation infrastructure is weak – the disease has proven slyly evasive of precise forecasting.

“This year we’ve had about 2.5 million doses per month available, new doses, and we expect to reach 5 million per month by the end of the year.”

- Allyson Russell, epidemiologist

“It’s a pretty simple bacteria that creates a huge amount of pandemonium,” observes Allyson Russell, an epidemiologist who is a senior programme manager in Gavi’s High Impact Outbreaks team.

The reasons for the pathogen’s outsize entropic force are pretty well understood. For instance, the bug lives in both humans and the environment and can jump back and forth. Changing weather – increasing rainfall, for example – can alter how it replicates and travels.

It also travels in our bodies – often secretly, because, in endemic areas, a high proportion of cases are asymptomatic. It takes as little as 24 hours for the infection to take hold in a new victim, and in severe cases, patients who do not receive treatment effectively become cholera bombs, excreting up to 20 litres of cholera-infected, profoundly contagious liquid in a day. “Basically, a substantial amount of the water you have in you, it comes out. And it contains a lot of bacteria. And as you can imagine, it can just go everywhere, risking making others sick as well,” says Russell.

Patients are treated with oral rehydration solution, a cheap and amazingly effective means of staving off death by dehydration. But cholera is fast, often outpacing overstretched health systems. Official tallies – likely a big undercount since not all cholera cases and deaths are reported to health systems or correctly diagnosed – say more than 4,000 people died of the disease last year alone, with 30 countries reporting outbreaks.

Vaccines are powerful tools for curtailing spread if used rapidly when an outbreak begins, or preventively in areas where outbreaks are known to occur.

That sounds simple enough, but presents logistical challenges. Optimising the use of the vaccines that we have demands the existence of a ready-in-the-wings trove of doses, poised to pack up and ship to wherever an outbreak flares, at a moment’s notice.

To that end, in 2013 – not long after cholera vaccines first became cheap and simple enough to use in outbreak settings – the International Coordinating Group (ICG) on Vaccine Provision called for the establishment of an oral cholera vaccine (OCV) stockpile.

Have you read?

That same year, Russell was beginning her master’s degree in global disease epidemiology and control at Johns Hopkins University and looking for some part-time work. “Quite serendipitously”, she began working for Dr David Sack, a legend in the cholera-control field.

Eleven years later, Russell and the stockpile are old friends. Recently, we sat down with her to talk about its revolutionary impact, its current limitations and its future.

VW: Let’s start with some material facts. What is the global oral cholera vaccine (OCV) stockpile? Is it a real place?

AR: Yes! The stockpile is a real, physical supply of vaccines. Which vaccines are stockpiled, and which manufacturers have been producing them, and consequently where that supply has been located, has changed over time.

At the moment, because we have a single supplier to the stockpile, which is EuBiologics in South Korea, the stockpile is housed in just one warehouse outside of Seoul.

VW: What does it look like in there?

As you walk in, part of the warehouse is the dry goods – the inputs to creating the vaccines. And then there’s the outputs, one section of which is a long corridor of refrigerators that are full of the vaccines waiting for orders to be placed.

VW: And currently, how well are those shelves stocked with stockpile doses?

AR: Well, that changes on a daily basis. What’s actually the more important piece of informationis the monthly production, and how quicklythe stockpile is replenished after orders go out.

That said, at this moment, there are just shy of three million doses on the shelf in Korea that are available for new orders right now. A couple million additional doses sitting there have already been purchased and are about to be shipped to countries with ongoing outbreaks.

What we would like is for there to be 5 million doses at all times: that’s the target value the ICG has set. But, as I’m describing to you, as soon as there are orders, these vaccines are sent and then these vaccines are replenished. And the requests used to be smaller – say 500,000 to 1 million doses in the years 2018–2020 – which at the current rate could be replenished within a week or two. But now that the orders are for 3 million, even up to 5 million doses, it takes a bit longer.

So, what we’re trying to do, and what we have been doing over the past years, is to increase the monthly production capacity. This year we’ve had about 2.5 million doses per month available, new doses, and we expect to reach 5 million per month by the end of the year.

VW: Can you explain why the volumes of the orders increased so much?

AR: Sure – and it is a very big difference. There are a number of factors. How the vaccine is used in outbreak response: for the first few years that the stockpile existed, the vaccine was seen as really a supplementary measure to the primary control measures for cholera – infection prevention and case management, provision of clean water and sanitation, community engagement, better surveillance. We hadn’t really used OCV substantially to do outbreak response, so exactly how to best use it was still being determined.

Then we were able to see the impact that OCV could have in very quickly controlling outbreaks, so countries became more interested – it became a more mainstream part of cholera outbreak response. Now I would say it’s one of the primary pillars in the multi-sectoral response plan, and a key question is, “How could we use vaccine to control the outbreak?”

Of course, the other control measures are really important: we want to emphasise that the vaccine is not a golden ticket out of the outbreak. But the vaccine has become much more prominent in how cholera outbreaks are addressed, as it does protect a population very rapidly if enough people in the area with active transmission receive it.

In addition, there’s less stigma around reporting cholera outbreaks, so there’s more political willingness to declare cholera outbreaks and request international support, including vaccines, for a response – that’s also driven an increase in demand.

Then, there are just more cholera outbreaks in the last three years than [there have been] in the years before that. There is a resurgence around the globe, with over 30 countries with active transmission and a substantial number of cases and deaths. That number was closer to 20 a few years ago.

Finally, cholera is affecting urban areas in new ways. With population growth, climate disasters and conflict, and the resulting destruction of infrastructure, especially sanitation infrastructure, cholera has been spreading in densely populated areas, and that’s putting a lot more people at risk. And when cholera spreads in large cities, it spreads much faster to the surrounding areas as well. Meanwhile, after COVID-19 and the drop in routine vaccination during the pandemic, there are a lot of other outbreaks happening too, and health systems and health workers themselves have less bandwidth to respond quickly and with the breadth of response needed, given how much they are managing at once.

VW: Even in the context of an acknowledged ballooning of demand, month to month, meeting the oscillating need for OCVs is a complicated business. There was a period, recently, when the stockpile was actually exhausted. Can you tell us about that? How unusual is it for the shelves to be empty?

AR: I would say it’s unusual, and certainly a situation that we hope to avoid at all costs. From my recollection it has happened only a few times since the creation of the stockpile over a decade ago. Usually these stock-outs occur for only a few days, as the vaccine is quickly replenished. Earlier this year we were out of supply for a few weeks, and the main reason was that a number of large orders happened all at once. The ICG has the challenging job of considering all needs for OCV around the globe at a given time, and equitably distributing according to the greatest need. When there are multiple ongoing outbreaks, this is not an easy task.

Producing for outbreaks is also very challenging. If you have a manufacturer who is producing without a forecast, they don’t know how many vaccines are going to be needed. In this case, the best they can do is have a constant monthly quantity and hope that that meets what the ongoing demands are.

But those demands are not constant at all. For example, in October of 2023, we ordered 9 million doses in accordance with ICG’s approved requests. And then, in May of 2023 and 2024, we ordered zero doses. And in between that it’s everything in between – on average a few million doses per month, but that’s also because that’s what production is, and currently nearly all vaccines produced are quickly sent to meet outbreak needs.

Basically, the shelves empty when you have one month in which, all of a sudden, you need more than the value of the stockpile. You use up the ongoing reserve, and you need a few weeks to replenish that. So that’s why we’re trying to speed up the replenishment process, which means having a larger monthly output of vaccines.

VW: I understand there’s reason to expect that supply patterns will change for the better with the arrival of a simplified vaccine called Euvichol-S. Can you tell us more?

AR: Yes. Euvichol-S received WHO prequalification in April – and the first doses were delivered to the stockpile this month. The arrival of Euvichol-S is expected to double the number of vaccines we have on a monthly basis, thanks to both having a simpler vaccine to produce, and more facilities in which to produce it. The release of this new vaccine is a testament to a very dedicated manufacturer and substantial partner support to bring this product to market.

VW: Am I correct to imagine that that will massively alleviate the pressure on the stockpile?

AR: That really depends on what happens with the outbreaks! What we’ve seen is that there is usually an increase in outbreaks in Q4, because of rainy season patterns.

What we want to do is give more visibility to the manufacturer on what the constant demand is – because they can’t continue to blindly produce double the number of vaccines every month if they’re not certain that these have somewhere to go.

That’s one reason why the preventive programme is really important: Beyond its primary goal of preventing outbreaks from starting in the first place and reducing the burden of disease on communities and the health system in known endemic areas, it will give the manufacturer visibility on what vaccines are needed on a regular basis to keep production going at maximum capacity.

VW: Let’s talk about the preventive programme. We’re currently using a very large quantity of vaccines every year in outbreak response – in 2023, it was 35 million. Those doses have done their jobs extremely well: a lot of lives have been saved. But my understanding is that deploying some doses complementarily in a preventive way – i.e. in at-risk places that are not currently facing outbreaks – might help doses go further. Is that about right?

AR: That’s definitely the idea. Preventive vaccination is recommended for areas that are very prone to outbreaks. Once an outbreak starts, it can spread to anywhere that’s at risk – meaning areas with poor water and sanitation – even if cholera is not necessarily endemic to all those areas. Our goal is to vaccinate people in the areas where outbreaks are likely to start, so they don’t start in the first place, and can’t spread to other places.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is the first country that Gavi has approved for preventive vaccination through the programme we launched in 2023. The country’s vaccination plan was approved earlier this year, in April, for a programme targeting 19.8 million people over three years. We’re working with them to start planning these campaigns, which we anticipate will begin next year.

It’s going to take a number of years to get to the point where all the highly endemic areas have a decent level of vaccination coverage. It’s not going to happen overnight, but it’s the direction we want to go in, certainly.

VW: Will preventive campaigns also use stockpile doses, or are these vaccines getting to countries via a different supply channel?

AR: The stockpile will remain for outbreak response needs, and responding when lives are at stake is always the top priority. With the expected expansion in the available global supply, we will be able to fulfil preventive vaccination requests in addition to what is needed for the outbreak responses. (Physically, we’ll probably still be looking at refrigerators full of vaccines that serve both purposes).

VW: Speaking of that room full of vaccines – is there a concern that in future, with production capacity jumping, doses could sit for too long and lose potency?

AR: Not really, because they’re fresh vaccines, and they have a two-year shelf-life. And as we’ve seen so far, if they’re not used in June, they’ll be used in July. We will also have countries that have multi-year preventive vaccination plans approved, and countries have been graciously flexible in adapting to what and when supply is available. Therefore, having both a preventive and an outbreak programme allows us to maximise the use of available supply and ensure all doses are effectively used, whether for prevention or outbreak response.

VW: Cholera is a disease of poverty, and though the bacterium travels with us, we don’t see outbreaks in countries with robust, reliable water and sanitation systems. Can you explain why the vaccine, though a life-saver, is not a substitute for good infrastructure development?

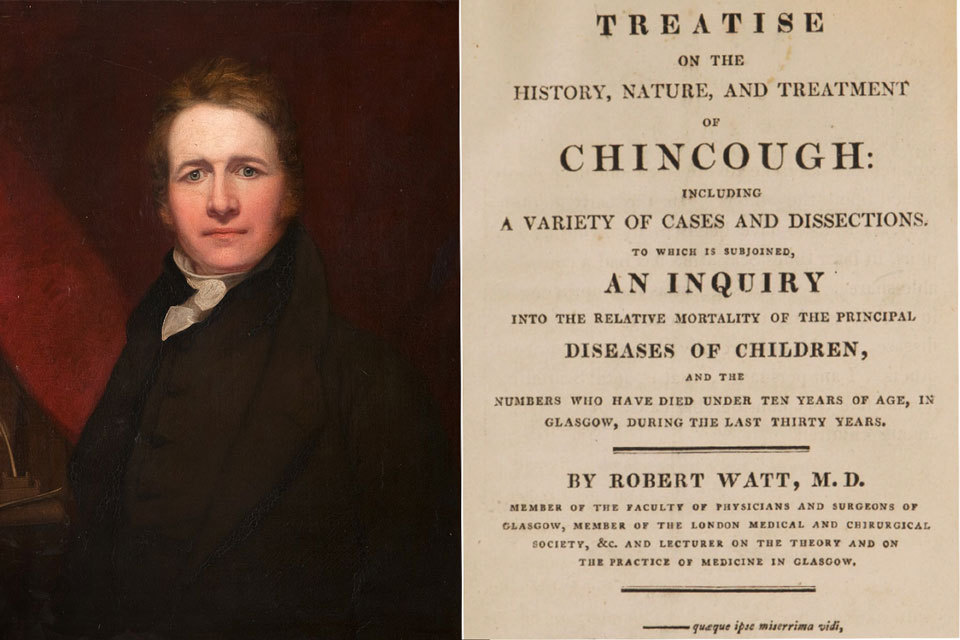

AR. Absolutely. I’d note that it was a cholera outbreak in central London in the 1800s that helped us realise that diseases could be transmitted through water and not just through noxious vapours (or mal-aria), so it certainly can occur anywhere there are inadequate sanitation systems.

But in the first place, this is not a perfect vaccine. It’s pretty good! But it’s not excellent. The protection wanes over time. If you get two doses, it is still protecting you after five years, but every year you’re losing a little bit of protection. It doesn’t work great in kids under five, so you need to achieve herd protection to provide children with the best protection.

That means you need to immunise just about everyone to make sure that at least 70% of the people in a given area are protected, and that will then knock down transmission enough to protect the whole community. This is hard to achieve at scale and is why we need to focus on improving water and sanitation systems for communities, not just continuing to conduct large-scale vaccination on repeat.

Then, in places where there’s cholera, there are a lot of other diseases such as rotavirus, polio, and all these other diseases transmitted via the faecal-oral route. So having a vaccine for one pathogen that works pretty well for only a few years really isn’t solving people’s actual need, which is for clean water and access to proper sanitation and hygiene.