Grin and bear it: new research suggests the Vikings were sicker than we thought

CT scans of 1,000-year-old skulls reveal that for Vikings, living with a whole lot of disease was normal.

- 19 March 2025

- 4 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

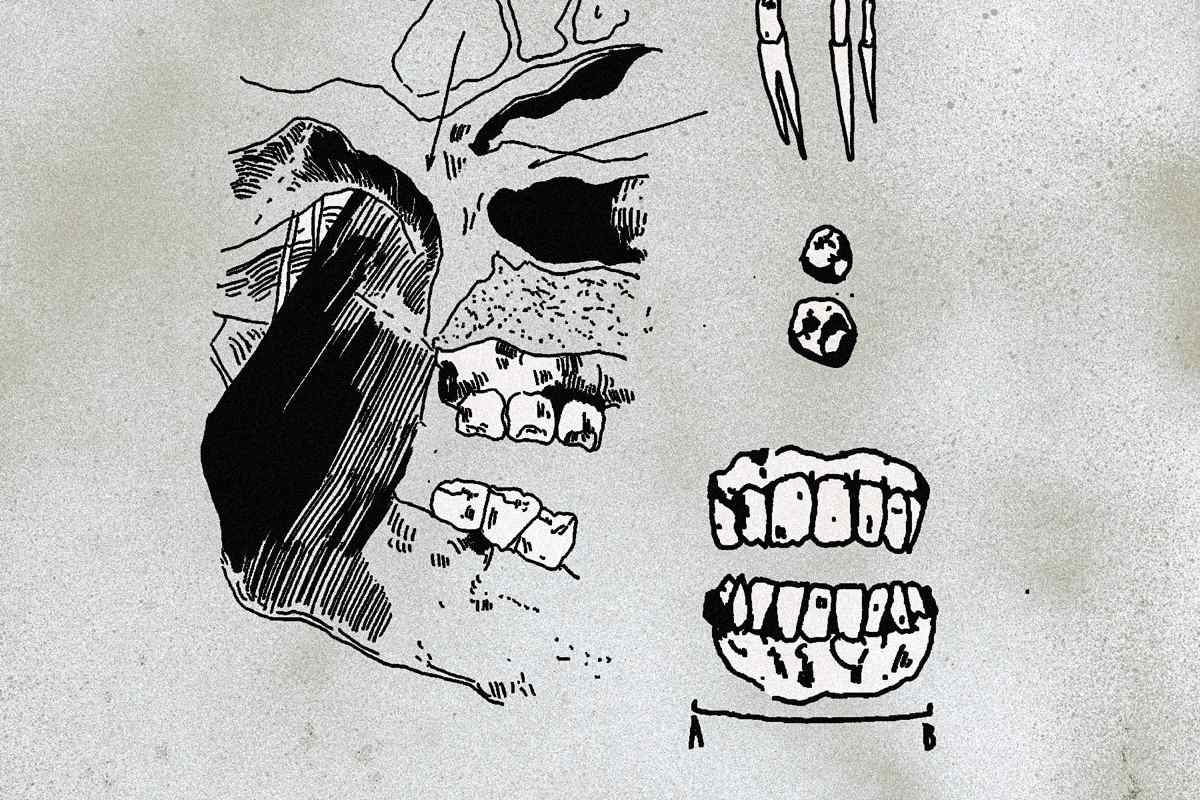

Computerised X-ray examinations of the teeth and jawbones of 15 individuals buried near Sweden’s oldest church between the 10th and 12th centuries have revealed that even those Vikings who stayed home and farmed – rather than going out on raids and taking spears to the head, or blades to the pelvis – knew how to suffer.

The new research, published in the British Dental Journal, suggests that they had little choice. All 15 individuals’ bones and teeth – the only material durable enough to survive the approximately 1,000 years that have elapsed since the Vikings in question died – bore signs of longstanding and progressed disease, with many of them afflicted with more than one persistent infection when they died.

Very old bodies, new insights

Unearthed with hundreds of other skeletons and partial skeletons on the grounds of Varnhem Abbey in 2005, the 15 skulls belonged to one of the very first Viking settlements to have converted to Christianity. The Varnhem remains, which show no signs of death in battle, have been extensively studied. But never before like this.

Researchers from the University of Gothenburg selected the 15 skulls – whose owners had been between 24 and 60 years of age, and included both men and women – from among a group of 171 previously-analysed remains, principally on grounds of their completeness.

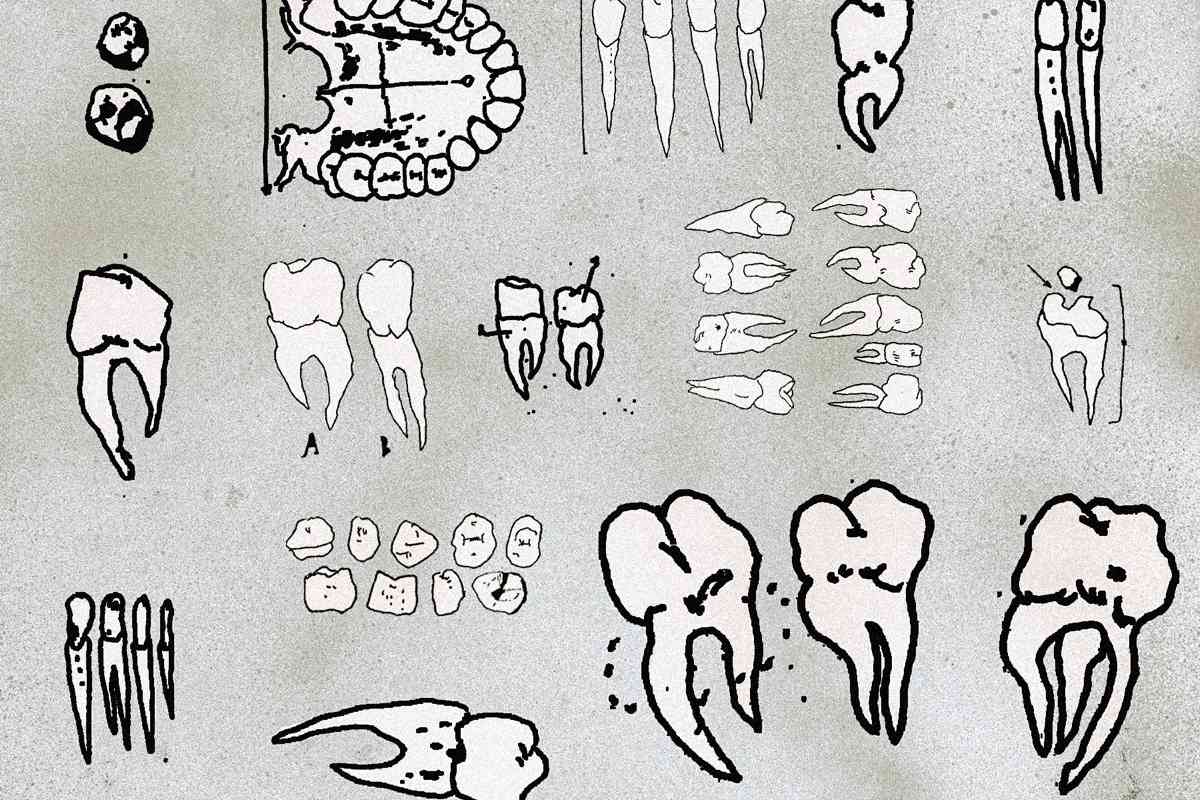

The researchers put these skulls through computerised tomography (CT) scanners, an imaging method that enabled a three-dimensional look inside the bones and teeth without damaging them.

“You can kind of scroll through the tissues,” lead author Carolina Bertilsson, a dentist who has often worked on archaeological research projects, told VaccinesWork. “It’s a really cool technique.”

Bertilsson and her colleagues embarked on the new research with few expectations. “We were kind of just going into this project to see, okay, what can we learn about these individuals? And we found a lot of interesting things,” she said.

Have you read?

Specifically, they found a staggering amount of sickness. Ten out of 15 of the Vikings the team studied suffered gum infections advanced enough to have precipitated bone loss and bone defects in the bone supporting the teeth.

Twelve out of the 15 individuals had periapical inflammatory disease, a lesion at the point of the tooth’s root that usually develops when bacteria invade the tooth’s pulp following tooth decay. In several cases, the lesions had actually perforated through into either the maxillary sinus – the hollow space in the bones around the nose – or into the oral cavity.

Eight out of the 15 had some abnormalities in their temporomandibular joint – the hinge of the jaw – including indicators of osteoarthritis. Several individuals bore signs that they had had sinus or ear infections that had caused the surrounding bone to thicken. The list of the pathologies the team found goes on. “For all individuals, there was something that we could find,” Bertilsson said.

All in, the imaging presented the researchers with a picture of life without effective medical care: a gradual accretion of health problems that often simply didn’t heal. “These individuals, they had a lot of different conditions that they were living with for very many years, and maybe it didn’t kill them, but they suffered a lot,” said Bertilsson.

Relatable – to a point

To Bertilsson’s mind, the findings constitute a kind of empathy wormhole into the past. While most of us don’t know what it feels like to take a sword-blow to the face, almost all of us, she points out, know the agony of a toothache or the pressure of a sinus inflammation.

“I think it’s very relatable,” she said. “I mean, it’s another time-period, and it’s hard for us to imagine what it was like to live in that time. I think when we think about Vikings we think about going out to sea, and fighting, and all of that – but there was also a life back at home, at the farm, or the village community, and you have to, you know, take care of your family, and at the same time you had all of these kinds of struggles, diseases and pains.”

But at the point where medicine begins, the comparison ends. “They just lived like that, because there was no treatment,” Bertilsson said. “When we have disease, we treat, and we also get vaccinations […] We wouldn’t think it’s normal to go with pain for several years.”