A 'new medical age': 70 years of polio vaccination

12 April marks the 70th anniversary of the world’s first polio vaccine, a world-altering technology.

- 11 April 2025

- 11 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

“An HISTORIC VICTORY over a DREAD DISEASE has dramatically unfolded at the University of Michigan,” crackled an announcer’s voice over velvety, black-and-white B-roll. “Here, scientists usher in a NEW MEDICAL AGE, with the monumental report that proves the Salk vaccine against crippling polio to be a SENSATIONAL SUCCESS.”

The date was 12 April 1955, and the monumental report that this News of the Day broadcaster1 was referring to, were the results of large-scale field trials of Jonas Salk’s polio vaccine, demonstrating that it was “80–90% effective” in preventing paralytic polio.

Seventy years later, that dispatch sounds quaintly hyperbolic. But even with hindsight’s sceptical squint, its verdict is unassailable.

During the first half of the 20th Century, the threat of polio loomed large over the US population, particularly during the summertime, when infections were at their peak. In the 1930s, the highest annual case tally had surpassed 15,000, and by the end of the 1940s, the yearly record was over 42,000 infections. The summer of 1952 would become America’s enduring polio high-water mark. That year alone, almost 60,000 Americans contracted the infection. More than 3,000 of them died, and 20,000 were left to live with some form of paralysis.

The Salk vaccine quickly kinked that trend-line into headlong decline, and almost instantly transformed the character of American summertime. Within a few years, it was clear that polio vaccination was changing the whole world.

Haunted summers

The poliovirus is probably very old. A piece of ancient Egyptian art from about 1400 BCE appears to depict a man crippled by polio; his right leg shortened, slack, atrophied; his weight supported on a cane – but for most of history, outbreaks of the paralytic disease appear to have been rare and confined in scale. Towards the end of the 19th Century, however, its epidemiologic patterns began to change, rapidly and alarmingly.

The first clear-cut epidemic on record occurred in Vermont in 1894 and comprised 132 cases of “infantile paralysis”. In 1911, the record for epidemic size was broken in Sweden, where 3,840 people fell ill in a single outbreak.

Then, in the summer of 1916, polio tore into the United States with unprecedented virulence. Nationwide, 7,000 fatalities would be recorded by year’s end. In New York City alone, 8,900 cases were recorded, with 2,400 left dead, and many paralysed.

The virus moved quickly. A child with a runny nose or sore throat would soon be writhing and sweating in bed, racked with electric shocks of pain and muscle spasms. The fever would calm, but in the worst cases, the pathogen would then attack the nervous system, causing paralysis, and sometimes death. Although some survivors regained the use of their affected body parts, many never did.

Parents were terrified, public health authorities clutched at straws. The mechanism of transmission was poorly understood. Playgrounds and swimming pools emptied out, movie theatres shut, streets were hosed down by white-shrouded sanitary workers and 72,000 cats2 were exterminated, just in case they had something to do with it.

The Salk vaccine quickly kinked that trend-line into headlong decline, and almost instantly transformed the character of American summertime. Within a few years, it was clear that polio vaccination was changing the whole world.

Nationwide phobia

For decades afterwards, American summers were haunted by the fear of another large-scale epidemic. War, and the Pandemic Flu of 1918, pulled focus for a while, but in the subsequent decades, the scale of the outbreaks ballooned, and the numbers of people living with the disease’s visible and disabling after-effects mounted. In 1932, America elected one of them as President: Franklin D. Roosevelt had caught the virus at age 39, losing the use of his legs overnight. By 1952, a survey of the American public found that only nuclear annihilation was a greater national phobia than polio.

Enter Jonas Salk

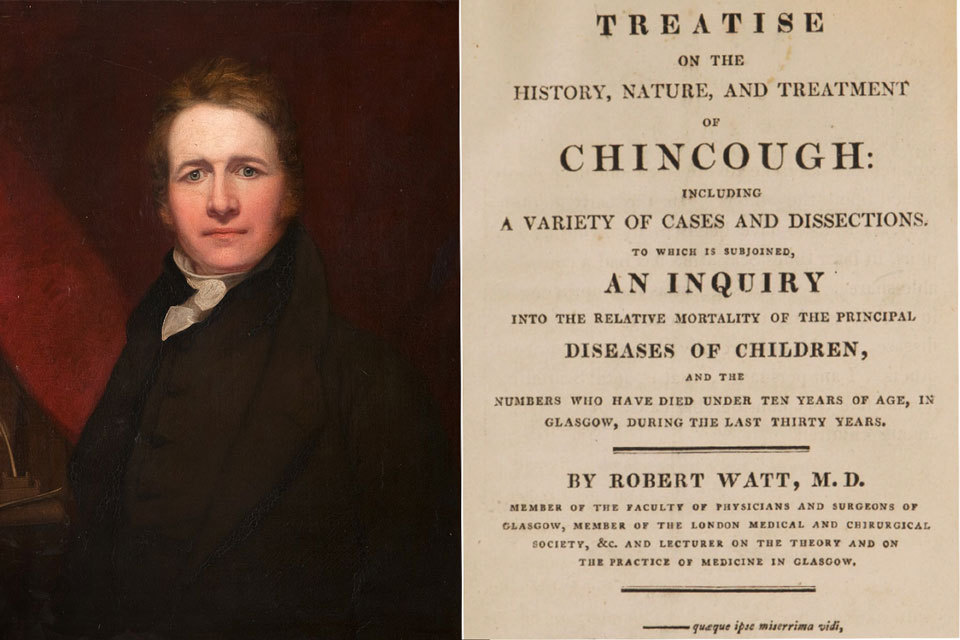

Jonas Salk, the eldest son of a working-class Jewish family from East Harlem, was two years old when that first major polio epidemic tore through NYC.

Clever and self-aware, Salk spent his childhood “waiting” – his word3 – to achieve something great. He won entry to a competitive prep school at 12 and went on to City College at 15. He was determined to do helpful work, and thought of becoming a lawyer, but his mother thought that was a bad idea, so he studied pre-med, going on to what would soon be renamed New York University’s College of Medicine.

An offer of a fellowship drew him from ward rounds to the lab bench, where he grew fascinated with the possibilities of using killed viruses to stimulate immunity. At this moment in time, there were just three vaccines in use against viral diseases – smallpox, rabies and yellow fever – and all of them relied on altered, therefore safe, live viruses to provoke an antibody response.

Conventional wisdom said killed alternatives would prove weaker than live-attenuated virus vaccines, and Salk hoped to rattle that orthodoxy. He found a research position under Thomas Francis, the new chairman of the Department of Bacteriology, who put him to work investigating the possibilities of inactivated – or killed – influenza virus.

Time passed, Salk returned to his medical studies, graduated, and began an internship at Mt Sinai. But a new war had begun in Europe, and by 1941, America was part of it. Salk wrote to his mentor Francis, the now at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, asking for a spot in his lab.

Francis had been asked by to lead the hunt for a flu vaccine to protect the troops from the kind of devastation that the armed forces had known in 1918. He brought Salk on board, and they set to work.

Parents were terrified, public health authorities clutched at straws. The mechanism of transmission was poorly understood. Playgrounds and swimming pools emptied out, movie theatres shut, streets were hosed down by white-shrouded sanitary workers and 72,000 cats1 were exterminated, just in case they had something to do with it.

By 1943 Francis and Salk were in a position to trial their vaccine candidate on soldiers. The results were thrilling: a 75% reduction of flu cases in the vaccinated group. In 1945, the army vaccinated 8 million soldiers with the vaccine Salk had played a key role in developing. Salk, now 31 years old, was making a name for himself – hungrily, and sometimes at the expense of his credibility5 among scientific peers.

He had always been ambitious: “You’ve got to admire ambition, especially when it’s combined with the kind of ability this fellow had,” Francis said of him. Now he was itching for independence. He left Michigan to set up shop in the only institution that would offer him his own lab – the underfunded and not especially reputable University of Pittsburgh.

His new fixation was on adjuvants – vaccine ingredients that could help stimulate a greater immune response, allowing the quantity of killed virus in the vaccine to be reduced – for flu vaccines. But he didn’t have the money he needed to do the work he wanted to do, so when Harry Weaver, director of the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, came knocking in 1948, Salk listened.6

Wanted: dead or live-attenuated

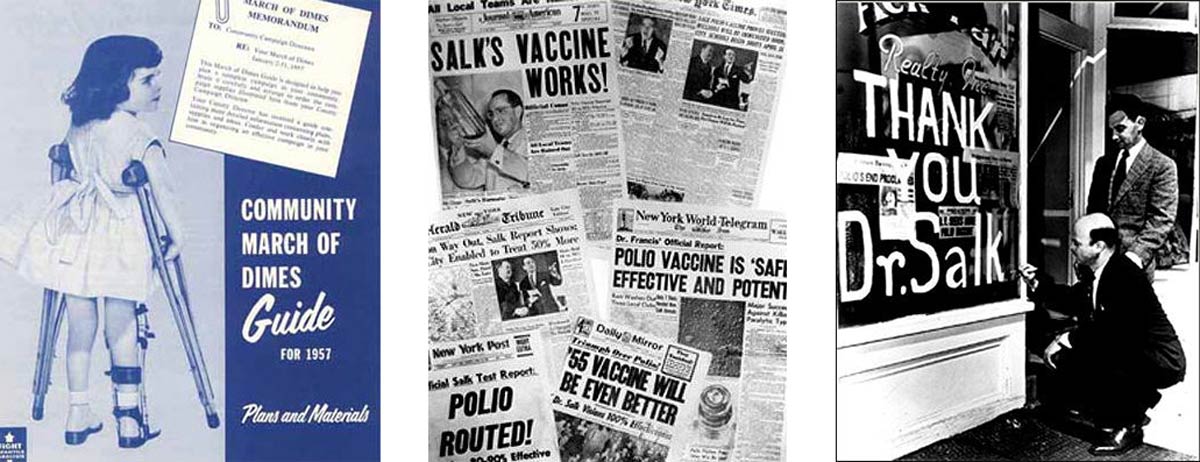

Founded by Roosevelt, the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis – best known for the phenomenally successful March of Dimes fundraising campaign – had money, a towering public profile and its sights locked on polio prevention.

That would certainly require a vaccine – but before one could be created, scientists needed to know how many strains, or types, of polio existed. In 1948, Harry Weaver was assembling a crack team of polio luminaries, including the brilliant and abrasive Albert Sabin, to work on what would necessarily be a large-scale, time-consuming and laborious research project.

Salk had never so much as attended a conference on polio, and did not strictly belong in their ranks. But Weaver liked the size of his imagination: “He thought big… he wanted to leap, not crawl,” he said.7 Indeed, as early as 1948, Salk was promising Weaver a vaccine within five years.

The typing project chugged on, costing millions of dollars and (sadly) tens of thousands of lab monkeys. In 1951, the investigators completed their work, concluding that there were three strains of poliovirus in existence. In the meantime, at Harvard, renowned scientist John Enders had cracked the tricky puzzle of growing polio in vitro, an achievement that won him and his teammates the Nobel, and removed a critical impediment to eventual vaccine production.

The race for a vaccine was on. Three scientists led the pack. Sabin and Hilary Koprowski, a scientist at Lederle Laboratories, worked on live-attenuated candidates, intended to immunologically mimic natural polio infection as close as possibly, while still being safe. Salk, instead, worked on a killed virus candidate.

Newspapers declared polio “conquered”, church bells rang, factories paused work. “It was as if a war had ended,” remembered one observer.

In 1951 America's leading polio scientists met at a National Foundation roundtable, where Koprowski announced he had a vaccine, based on poliovirus that had been passaged through cotton rats to reduce its chances of causing disease in humans. He and a colleague had tested it on themselves three years earlier, drinking a blended soup of ground rat brain and spinal cord teeming with the altered poliovirus; they had tested it on twenty other volunteers since. Within ten years Koprowski’s vaccine would be in use on four continents. Sabin’s live vaccine, meantime, would go to trial at the end of the decade, and, during the 1960s, become the most popular formulation.

But the urgency was high. Disease rates were spiking, and it was Salk’s candidate that was nearing use the quickest. Salk's product entered the first tentative tests – in children who already had polio antibodies from natural exposure, as a form of harm-limitation – in mid-1952,8 that plagued summer.

It performed well. By 1953, Salk had the confidence of an influential group of people, including virologist Tom Rivers, who declared “if I had a kid, I wouldn’t have hesitate one minute to inoculate him … with Salk’s vaccine.”9 His backers also crucially included the bosses of the National Foundation who, through a new Vaccine Advisory Committee, began planning the Salk vaccine trial – “the largest medical experiment ever attempted,” in historian David Oshinsky’s words – in March that year. A group of 1.3 million children would take part.

Have you read?

Triumph, and tragedy

“The vaccine works,” read the press release that went out on 12 April 1955, after Thomas Francis at the University of Michigan concluded his evaluation of the trial: “It is safe, effective and potent.” Not, perhaps, universally as effective as touted, given that its protectiveness against Type I polio hovered in the lower band of 60–70% – but the fact remained that this new technology had the power to turn the tide on polio. Newspapers declared polio “conquered”, church bells rang, factories paused work. “It was as if a war had ended,” remembered one observer.

But a setback lurked in the wings. On 27 April, it was discovered that a faulty batch of vaccine, whose production standards deviated from Salk’s guidelines, had been released by Cutter, one of the five manufacturers tasked with the vaccine’s production. Some 380,000 children had received a bad dose; 220,000 of those children suffered a brief case of polio and recovered; and 164 of them were paralysed. Ten died.

The roll-out paused, production rules were rapidly overhauled, and so were the standards for safety testing. “The additions [to the process] proved remarkably successful,” writes Oshinsky. “There would be no more Cutter incidents.” But the tragedy exacted a steep toll on public confidence, denting vaccine uptake rates. According to Oshinsky, of the more than 28,000 cases reported in 1955, “most … could have been avoided.”

The vaccine pleaded its own case: polio rates nosedived among the immunised. Meanwhile, celebrity champions jumped aboard, including Elvis Presley. The extent to which Presley getting the jab, live on the air, before an audience of 60 million viewers in late 1956 made a difference is hard to unpick, but vaccination rates among American youths would leap 80% over the next six months. By September 1961, 77% of the population under 40 years of age had received at least one inoculation. That year, the polio case count had dropped below 1,000 for the first time since 1900.

As new vaccines joined the immunisation arsenal, disease rates would keep falling. In 1979, the US recorded its last case of wild poliovirus.

End game

Country by country, the rest of the world has largely followed.

In 1980, 50,000 cases were still reported worldwide. But since 1988, when the Global Polio Eradication Initiative was established, disease rates have decreased by more than 99%. The wild-type virus remains endemic in only Pakistan and Afghanistan. A pincer movement of killed and live-attenuated polio vaccines is helping the world close in on eradication.

Monumental progress against polio has been made over the past 70 years. Thanks to Salk’s vaccine and others that followed, we now stand at the brink of another new medical age: a world without this dread disease. If polio is eradicated, it would be only the second human disease to be so, after smallpox. That truly would be a historic victory.

2 Much of the description of the summer of 1916 is taken from Charlotte DeCroes Jacobs’s book, Jonas Salk: A Life

3 Quoted in DeCroes Jacob’s book

4 Squeamishly enough, the precursor to this human trial was one run on the inmates of a “Hospital for the Insane”. Human research subjects would be protected by ethical research principles only after the Nuremberg trials.

5 Writing magazine articles in the popular press and taking on paid consultancies for pharma companies on the side were not the standard comportment of research academicians.

7 Ibid.

8 Read more in David M. Oshinsky’s Polio: An American Story

9 Ibid.