Giant-killers: 7 historic deaths and the diseases that did it

From Alexander the Great to Mozart, some of our mightiest historical figures were felled by the tiniest of microbes. But which diseases killed them and – more importantly – how can you avoid their fate?

- 14 February 2025

- 19 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

We are flung crying into the world, in some place, on some rung of the social ladder and at some moment in history, and that conjuncture has a great deal to do with how long we get to stay.

Among contemporaries, disease far more often emphasises disparities of advantage than levels it – this is an avoidable, culpable fact. But even giants (whether elevated by birth or achievement or both) are perfectly vulnerable to being born too soon. Here are seven of them.

At the deathbed of Alexander the Great, world conqueror

Babylon, 323 BCE: For more than a week Alexander has been slumped somewhere in the back palace. It’s early June, hot in Mesopotamia, but the sweat is from the sickness. He is 32 years old and he is dying.

The anteroom of death is certainly familiar to him. At the head of the ten-year offensive that conquered him most of the known world, he has survived a shattered shank, an arrow-pierced lung, severe bouts of gastrointestinal illness and dangerous fevers.

Lately, he has been surviving surviving his closest friend and lover, Hephaestion, killed by disease. Grief has launched Alexander on a seven-month spree of drink and partying. He was downing wine when the first symptoms hit him – fever and (according to some sources) sharp abdominal pain. Rumours of poisoning follow him to his sick-bed.

A day later, Alexander feels suddenly better: gets up, plays dice, eats well. Another day after that, he is felled again. After a week of the fevers, he is too feeble to make his daily sacrifices without physical assistance, and soon he is stilled, has stopped even crying out: his illness has cost him his speech. By the evening of 11 June, 323 BCE, Alexander III of Macedon is gone.

Weirdly – or perhaps not for a man who will be worshipped as a god – his corpse lies for six days untouched and yet unchanging in the heat. “Those who approached saw it spoiled by no decay... Nor had his face yet lost that vigour which is associated with the soul,” recorded the Roman historian Curtius.

The likely perpetrator: In 1872, the French Physician Emile Littré pointed out that Alexander’s symptoms seemed to track the violent and erratic disease course of falciparum malaria.

Alexander had survived what was almost certainly malaria in Cilicia in 333 BCE, “the most virulent malarial location in Anatolia” according to historian David Engels. Violent relapsing fevers and insomnia took him out of action for two months during his pursuit of the Persian king Darius. Was his final illness a recurrence?

In his book Post Mortem, medical professor Dr Philip Mackowiak – who is also the director of the annual Historical Clinicopathological Conference at the University of Maryland, which makes such long-ago diagnoses its object – concedes it’s possible, but finally argues otherwise.

What then? In Mackowiak’s view, the most likely explanation for Alexander’s symptoms is typhoid, an acute infection with the bacterium Salmonella typhi that spreads in contaminated food and water.

“Prior to the discovery of antibiotics in the mid-20th century, typhoid was a disease marked by prolonged fever and progressive debilitation. In rare instances, the infection was accompanied by an ascending paralysis involving first the legs, then the arms, and finally the area of the brain that controls breathing.

“This form of paralysis, the so-called Landry-Guillain-Barré syndrome, is virtually universally fatal when due to typhoid fever,” he writes. One explanation for Alexander’s undecaying body, then, is that he wasn’t dead – at least, not yet.

How not to die like Alexander: Typhoid is still a threat. An estimated 9 million people got sick with typhoid in 2019, according the World Health Organization (WHO), and 110,000 of those died.

As Mackowiak indicates, the advent of the era of antibiotics made typhoid a far more survivable illness. That said, drug resistant (since the 1970s) and extensively-drug resistant (more recently) forms of the bacterium are spreading at accelerating rates.

Good news, then, that we have vaccines. In 2017, a new and improved jab, the typhoid conjugate vaccine (TCV), was prequalified by WHO. Since 2018, Gavi has been funding the roll-out of TCV in the most at-risk countries in the world – an effort that studies have found could avert as many as 46–74% of all typhoid cases.

Malaria, meanwhile, kills about 600,000 a year, most of them children, but is the very latest addition to the ranks of vaccine-preventable diseases. Babies in the highest-risk countries on earth are accessing protective doses – but their parents are warned not to dispense with the older prophylactics, like nets, chemoprevention, sprays and fogs.

At the deathbed of Saladin, Sultan of Egypt, Syria, Yemen and Palestine

Damascus, 1193 CE: Salah ad-Din Yusuf – Saladin, to his Crusader enemies, his followers and to posterity – is ill again.

In recent days, the Sultan has felt weak and occasionally seemed a little vague. On a Friday night in mid-February, he suffers through an attack of bilious fever; on Saturday, at lunch, his son sits in his place at table, and Saladin’s friends weep, afraid that the substitution is an omen.

He has begun to say that he is old. In fact, he is 56, and in his followers’ eyes still the same brilliant and kind leader – with this judgement of his virtues, even his great nemeses concur – that he has been since 1169, when he first took command of the Syrian army and led them to a string of dazzling conquests.

But it’s true that since a couple of years before his triumph over the Franks at Hattin in 1187, gateway to the Muslim re-conquest of Jerusalem after 88 years of Crusader control, his health has begun to flicker. An illness, probably febrile in nature, laid him up for much of the first half of 1186. He recovered, but apparently imperfectly, and has since suffered recurrent bouts of a sickness characterised by fever and stomach complaints.

Now, four days have passed, and his final malady is advancing. Court doctors bleed him in an effort to relieve the symptoms; if it helps, it helps fleetingly. By the eighth day, his mind begins to wander. On the ninth day, he is all but limp, and Damascus begins to grieve; on the tenth day, he is treated with enemas. He starts to perspire, and his attendants are buoyed with optimism, reading it as a turn for the better.

But the sweating is too copious, unrelenting: on day 11, it has soaked through the mattress and is beading on the floor. The night after that, Saladin’s biographer and devoted friend, the Imam Beha Ed Din Abu El-Mehasan Yusuf, records that his “strength failed […] he remained sometimes with us, and sometimes wandering.”

Early in the morning of 4 March, a Thursday, as an attendant reads to him from the Koran, he dies. The Muslim world, briefly united at his back, will soon begin again to fragment.

The likely perpetrator: What killed Saladin? In his book Diagnosing Giants, Mackowiak examines the candidates. Malaria, typhus, typhoid and leptospirosis – all “almost certainly prevalent in medieval Palestine” – are each considered, but finally passed over in favour of a disease that better fits both the symptoms (think night-sweats and disorientation) and the season (winter: bad for mosquitoes).

“Saladin lived (and died) during a time of widespread tuberculosis. Although there is no evidence that he suffered with scrofula, his terminal fever, night sweats, headaches and progressive disorientation do suggest he died of a different form of tuberculosis, namely tuberculous meningitis, tuberculosis of the membranes covering the brain and spinal cord,” Mackowiak writes.

How not to die like Saladin: Unfortunately, some 1.5 million people still die of infection with the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis each year.

We’re far from medically helpless, but we also haven’t (yet) scored the pharmaceutical knock-out blow. We have drugs to treat tuberculosis, and most of the many millions of cases diagnosed each year are curable. But antimicrobial resistant strains of TB are a growing, and frightening, problem.

The world’s first TB vaccine (called the BCG vaccine), meanwhile, has been rolling out at large scale since as long ago as 1924. It has saved many young lives. But the BCG jab’s protectiveness has been shown to wane as children get older, and does not protect adults. New, better vaccines are urgently called for, are in development, and have been earmarked as a priority for support from Gavi.

At the deathbed of Peter II, Emperor of Russia

Moscow, 1730: His life has been brief and marked by bitter precocity: orphaned at three, on the throne at age 11. Now he is 14, and it is his wedding day, but instead of marrying, he will die.

For the three years Tsar Peter II has been in power, he has shown no especial interest in governing, and his reign is marked by feasts and parties in the palace and by administrative chaos in the empire. In mid-January, Peter attends yet another feast, outdoors. There’s ice and snow on the ground, and at first it seems he’s caught a chill.

Then the doctors make their diagnosis. It’s the smallpox – marked by pustules and high fevers, pain and gastric symptoms – and the young emperor has little hope of recovery. In the early morning of 30 January, the would-be-bridegroom nonsensically declares his intention to visit his sister, long dead. Then he joins her. With him dies the male line of the Romanov dynasty.

(NB: About a decade and a half later the teenaged bride of Peter III, who will become Catherine the Great, arrives in Moscow. She outmatches her husband for political savvy and takes the helm of Russia. Among the modernising reforms she pushes is preventive inoculation: in 1760, she undergoes variolation, the riskier forerunner to vaccination. Surviving it, she signs her son and heir up for the procedure, and starts a trend. By 1800, 2 million Russians have undergone variolation, and are smallpox immune.)

The perpetrator: Smallpox is caused by the variola virus, one of the most devastating pathogens to make its mark on world history.

How not to die like Peter II: No need to worry. Smallpox was eradicated by a massive, world-wide vaccination campaign that reached its definitive conclusion in 1977, when the very last smallpox patient recovered from the disease in Somalia (he went on to work as a polio vaccinator).

At the deathbed of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, composer

Vienna, 1791: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart has never been a person of vigorous constitution, but all the same, the final illness comes on abruptly.

He is 35, but his legacy belies his young age. For nearly all of his life he has been putting his native genius brilliantly and diligently to work: he will leave behind a large catalogue of world-changing music.

Now he is in bed, feverish, prickled with rashes, tended by his wife and sister-in-law, who pause at the threshold of the room to catch a lungful of air: the dying man, unfortunately, stinks. They clean and change him but the odour is coming from inside. His body has swollen, and he no longer looks quite like himself. He complains of severe pain.

But he is not done working. On day 14 of his illness, some friends stop by to sing pieces of his Requiem to him. On the next day – his final day – he sings snatches of the composition to composer and friend Franz Süssmayr, who copies it down.

Just after midnight on 5 December, he shudders, vomits and dies.

The likely perpetrator: A local physician called Dr Thomas Closset names the cause after Mozart’s death: hitziges Frieselfieber, which translates approximately to acute miliary (a word which refers to small-sized skin papules) fever. It’s strikingly unhelpful: scholars will later label the diagnosis as “nebulous”, and assert that at no point in history has there been a deadly condition conventionally described by that name.

In the centuries to follow, a profusion of discordant retrospective diagnoses jostle for authority: poisoning (summarily dismissed here), syphilis, infections of various kinds, stroke.

Especially compelling is the cluster of scholarly opinion that converges on streptococcus-triggered inflammatory or autoimmune conditions.

Writing in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine in the 1980s, clinician Peter J. Davies proposed as a terminal diagnosis Schönlein-Henoch purpura, an autoimmune condition that is typically triggered by viral or bacterial infection.

An epidemiological analysis from 2009 discovered a relative surge in deaths with oedema (think of Mozart’s swollen body) in Vienna in the months surrounding the composer’s death, pointing to an epidemic illness – and the study authors propose infection with streptococcal bacteria leading to acute nephrotic syndrome.

Mackowiak, too, comes down on the side of poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis – a dangerous immune response triggered by infection, and proposes Streptococcus equi, contracted due to the consumption of contaminated milk or cheese, as the most likely responsible pathogen.

The smell his attendants complained of at his bedside was quite conceivably the stench of the accumulating waste products in the body that the broken kidneys were longer filtering out. Doctors today call it “uremic factor”.

How not to die like Mozart: Strep infections are extremely common, but not, in most cases, severe or fatal. That said, the sheer prevalence means that group A streptococci do qualify as a “major cause of death and disability globally”, according to WHO, especially due to rheumatic heart disease subsequent to autoimmune inflammatory reactions to the infection.

The hunt for a vaccine against strep A is ongoing. Studies suggest their development could not only directly save lives, but also drastically cut down on antibiotic use for sore throats, potentially helping slow the rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Despite rising rates of AMR, antibiotics can still help beat back the infection. If autoimmune inflammatory responses like Mozart’s are triggered, doctors can use steroids and anti-inflammatory drugs in many cases to calm the effects.

But it’s also important to consider that Mozart’s final illness was far from his first – and that many writers have converged on the idea that what killed him was either an effect or a recurrence of prior illness.

The body’s victory over an invasive pathogen often isn’t a total rout. Some infections have distinct sequelae – lasting complications – and in other cases the after-effects may be enfeebling in a more diffuse and even accretive way. A 2025 study found that children exposed to frequent infections in their first years may be at greater risk of “moderate to severe illness” later in life.

In the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, clinician Peter J. Davies (who, as mentioned earlier, proposed as a terminal diagnosis Schönlein-Henoch purpura) also tabulated Mozart’s lifetime of illnesses, translating descriptions in the written sources to plausible modern diagnoses. The list, 18 episodes long, includes but isn’t limited to: streptococcal upper respiratory tract infection, upper respiratory tract infection, tonsillitis, typhoid fever, smallpox, viral hepatitis or yellow fever.

The argument in favour of prevention is implicit and robust. Vaccines (available against typhoid, smallpox, viral hepatitis, various kinds of respiratory infections and yellow fever) are an important part of that. But so are other investments in health, like nutritious meals (poor baby Mozart was fed on a diet of barley water), clean water and safe cheese.

At the deathbed of Manuela Sáenz de Vergara y Aizpuru, revolutionary

Paita (Peru), 1856: A poor handicraft-vendor, once a trader in powerful intelligences and a deft cultivator of revolutionary loyalties, is writing a letter. “I am very sick of the face [throat],” she reports to her friend.

Picture her as fellow exile Giuseppe Garibaldi found her in 1851, when he stopped by to hear her stories: “majestic,” despite her penury, and despite the fact that she has grown heavy with advancing middle age and a loss of mobility. She knows what it is to live as an aristocrat, to wear a colonel’s uniform, to wield great influence, to be loved by El Libertador, to hack out a rebel’s path.

Many of her treasures must be lost to her, living out her last chapter in this “pitiful hut”, but her honours are inalienable, like the Order of the Sun of Peru, and Simón Bolívar’s titles for her: “dear madwoman”, “la Libertadora del Libertador” – the Liberator’s Liberator.

She signs off. It is the last known letter in an important epistolary career, and here history loses sight of Manuela Sáenz de Vergara y Aizpuru for a while.

But meantime, an epidemic of diphtheria is burning through the region, perhaps having made landfall on a ship from England, where a similar outbreak raged a year earlier. Medical intervention in the 1850s is largely futile. People die choking, their throats swollen thick with grey, dead tissue. Mortality rates during outbreaks have been recorded to reach 90%.

On November 23, Manuela’s friends record that she has died of sickness. In Paita they say she was consigned to an anonymous mass grave filled with the corpses of diphtheria victims on the town’s outskirts.

The perpetrator: Diphtheria is caused by infection with Corynebacterium diphtheriae, a bacillus that spreads in airborne droplets, and is capable of releasing a tissue-killing exotoxin. The most dangerous form of the disease hits the respiratory system, and even with proper medical care, one in ten patients is expected to die.

How not to die like Manuela Sáenz de Vergara y Aizpuru: We have a very good vaccine. Commonly offered with tetanus and pertussis vaccines in the three-in-one DTP jab, considered a core building block of global childhood immunisation programmes, or as part of the five-in-one (DTP-Hib-hepB) pentavalent shot, the diphtheria vaccine was, in 2023, protecting 84% of the world’s children. But like so many contagious illnesses, a dip in global immunity after COVID-19 proved that even minutely lowered defences can allow for resurgence: deadly outbreaks flared again. When outbreaks occur, the best therapy hinges on a combination of antibiotics to kill the bacteria, and antitoxin to neutralise the exotoxin.

At the deathbed of Oscar Wilde, writer

Paris, 1900: The guest registered as Sebastian Melmoth, resident at the Hôtel D'Alsace and other similarly sordid establishments in Paris these past 18 months, has called for a priest.

It’s late November. Since September, the guest has been visited 68 times by a doctor, but now it’s too late for the salvation of his body and he wants spiritual intercession. This is notable, because Sebastian Melmoth is the writer Oscar Wilde, known less for piety than for his words, his wit, his glittering life and lately for the scandal of his 1895 conviction on charges of “gross indecency”.

The conviction – for having sex with men, a criminally liable act in 1895 and formally still until 2004 – put him for two years in Reading Gaol. He was released in 1897, but Wilde says the internment has broken his heart.

More pertinent to his current moribund condition is the fact that his reduced circumstances have at least presided over, if not precipitated, the aggravation of a longstanding ear condition.

The complaint, located in his right middle-ear, began at some point before his incarceration, but by 1896 it had progressed dangerously. In a petition to the Home Secretary that Wilde made from prison that year, he described an abscess in the right ear that had perforated and drained continuously, resulting in an almost total loss of hearing on that side. “Nothing has been done in the way of an attempted cure,” he wrote.

It’s the same ear, flaring up again, that prompts Wilde to see Dr Maurice a’Court Tucker so many times in these final months. In October 1900, the physician attempts a radical surgery in Wilde’s hotel bedroom. Days of wound dressing, morphine and opium follow. Late in the month there’s brief cause for optimism, when Wilde is able to go out into the city.

But in mid-November the infection resurges. By 25 November, he is so dizzy he can’t get up, and in another day he is now delirious and nonsensical, now lucid. He won’t eat, he’s fractious, he’s burning with fever, and then he’s unconscious. On the afternoon of 30 November, Wilde dies, aged 46.

The likely perpetrator: The doctors who signed the death certificate, Dr Tucker and a French physician called Dr Paul Claisse, were definitive in their diagnosis: the cause was cerebral meningitis – inflammation of the lining of the brain – resulting from a chronic suppuration of the right ear.

The pathogenic cause of the infection that infected the ear and inflamed his brain has been a question of debate. A speculative diagnosis of syphilis, first proposed by Tucker, has endured – no doubt stiffened by prurient bias.

But many credible analysts say the fact that Wilde’s cognitive function was unimpaired up until his final hours, as well as the fact that none of the many doctors who examined him in his lifetime recorded syphilitic symptoms, make it improbable.

One hundred years after Wilde’s death, South African ear surgeons Ashley H. Robins and Sean L. Sellars examined the records and wrote in The Lancet that the root of the ear problem may have been a cholesteatoma – a fast-moving tumour, yielding chronic infection. (Many pathogens could be behind the infection, but speaking generally for middle-ear infections, the bacteria Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenza are common culprits.)

Antibiotics were first discovered 28 years after Wilde’s death, which means the infection raged all but unchecked – a terminal peril. Wilde’s own father, an ear doctor, happens to have written in an 1853 textbook: “So long as otorrhoea [ear discharge] is present, we can never tell how, when, or what it might lead to.”

How not to die like Oscar Wilde:

Few gamblers would take the odds that meningitis affords its victims. The condition is a consequence, not a cause, of infection, and the causes can be many, but once an invading pathogen has excited inflammation of the brain, the risks of not recovering at all, or not recovering fully, are alarmingly high. Bacterial meningitis is the most dangerous form: one in six people who contract it die, and one in five survivors live on with enduring disabilities.

Combatting illness before it reaches the brain is, of course, far more possible now than in Wilde’s day. Today, a condition like his otitis media could likely be well-managed or resolved with antibiotics or antivirals and modern surgical techniques to resolve structural predispositions.

And today, some of the most common culprits behind deadly meningitis are vaccine-preventable, obviating therapeutic pitched battles. A jab called MenAfriVac – which blocks the serogroup A meningococcus bacterium – began to roll out in 2010 across the so-called “meningitis belt” of Africa, with astounding effect.

We also have vaccines to ward off meningitis-causing pneumococcus and Hib and last year, for the first time, a vaccine that blocks five different serogroups of meningococcal bacteria began to roll out to contain a meningitis outbreak in northwest Nigeria.

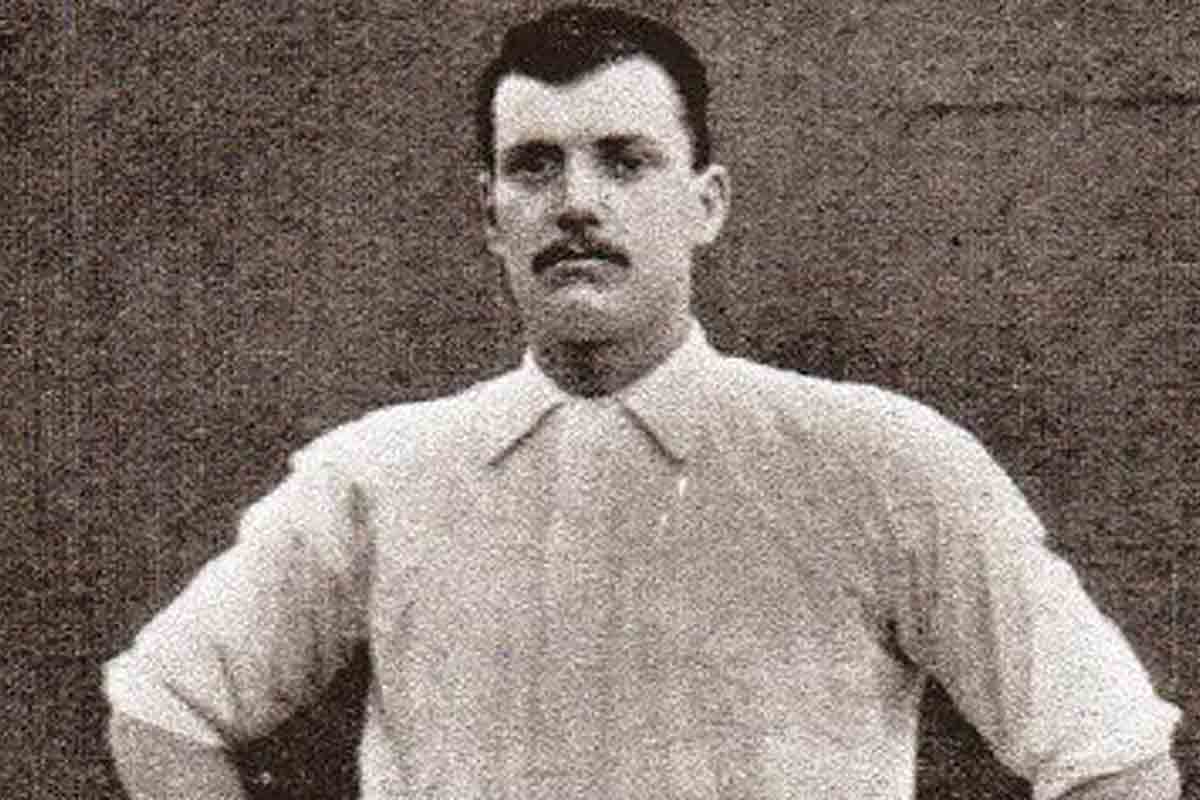

At the deathbed of Di Jones, footballer

Bolton, 1902: Manchester City footballer Di Jones – “one of the finest full backs the game has known,” according to the Bolton Evening News – walked off-field after his injury, though the injury was nasty: a three-inch, bone-deep cut to the knee, caused by a shard of glass in the turf.

He took himself to the Manchester Royal Infirmary, where the gash was dressed and stitched, and then took the train home to Bolton to recover.

Instead of recovering, however, he is sick: feverish, sweat-glazed, heart thumping, in pain. A doctor has been called, and finds the leg wound to contain debris and bits of grass. Symptoms of “blood poisoning” advance, the doctor says, “and set up tetanus, or lockjaw”.

It’s called that because of the violent muscle spasms of the back, abdomen and jaw, which seems soldered shut. The spasms can block airways; the disease can damage the nerves and precipitate organ failure.

A week and a half after cutting his knee, Jones, aged 35, dies.

The perpetrator: The sickness is caused by the toxins released by a bacterium called Clostridium tetani, which attack the central nervous system and interfere with signals that travel from the spinal cord to the muscles. The resultant spasms can be violent enough to snap bones.

C. tetani spores are found almost everywhere – in faeces, in soil, on rusty metals. In Di Jones’s day, small skin wounds quite often turned fatal as a consequence – and the sports pitch was a common origin point for infection. “A basic search of newspaper archives finds dozens of deaths caused by tetanus contracted during games of amateur football,” wrote Guardian journalist Simon Burnton in an article recalling Di Jones’s death.

How not to die like Di Jones: Still today, tetanus kills around 10–20% of the people it infects, but a complete series of the vaccine is virtually 100% protective.

The tetanus vaccine forms part of the basic childhood combo-jab, either in the three-part diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis form (DTP), or in the five-part pentavalent vaccine. As of 2023, 84% of the world was protected with the recommended three doses of DTP – but when coverage dips, infections with this widespread pathogen are quick to crop up and threaten lives.

Further reading

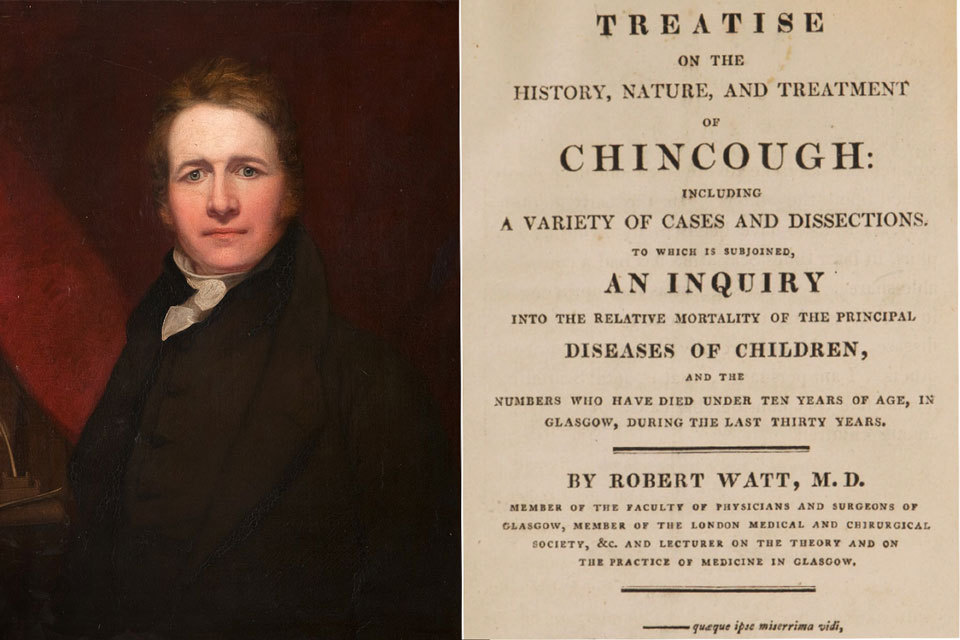

This article – in particular the sections on Alexander, Saladin, and Mozart – is especially indebted to two books by Philip A Mackowiak, professor of medicine at the University of Maryland, and director of the annual Historical Clinicopathological Conference. They are: Post Mortem: Solving History’s Great Medical Mysteries (2007) and Diagnosing Giants: Solving the Medical Mysteries of Thirteen Patients Who Changed the World (2013).

The section on Manuela Sáenz de Vergara y Aizpuru borrows principally from Pamela S. Murray’s biography: For Glory and Bolívar: the Remarkable Life of Manuela Sáenz.