Five ways meningitis vaccines are saving lives

Vaccines that tackle the causes of meningitis are crucial to the 2030 goal to eliminate the disease – here’s how.

- 1 October 2024

- 3 min read

- by Priya Joi

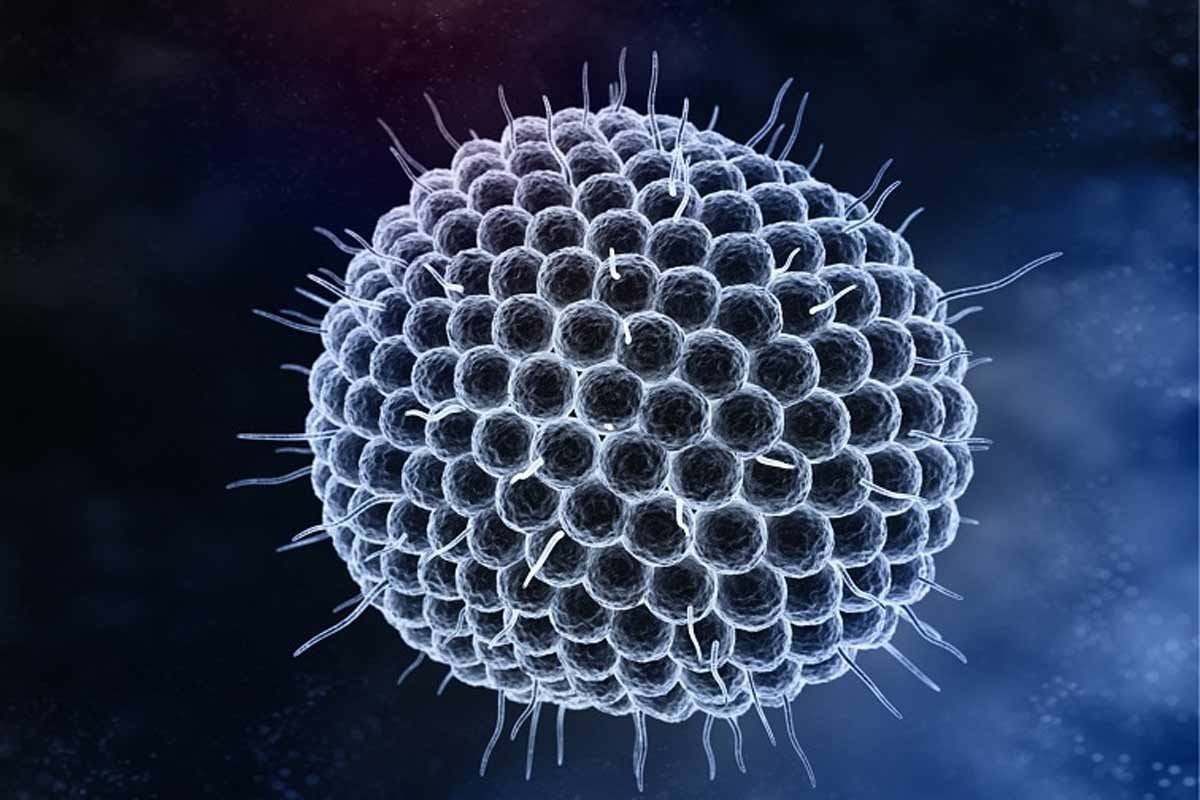

1. Protecting against the multiple causes of meningitis

Between 2000 and 2023, it is estimated that over 41 million lives across 112 low- and middle-income countries have been saved by vaccines that protect against causes of meningitis.

Vaccines are most commonly given to babies and young children, who are at the greatest risk of infection as their immune systems are still developing. They are also given to people with compromised immunity, which means their risk of developing meningitis is greater than other adults. However, many other people can be at risk as well – meningitis can be caused by multiple pathogens, both viral and bacterial.

This is why some countries have introduced meningococcal group C (MenC) and meningococcal groups ACWY (MenACWY) vaccines to protect against specific strains of meningitis, including meningitis W, which can cause infections in adolescents and young adults.

2. Massively reducing Hib infections

Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) causes one of the most common types of bacterial meningitis. The vaccine against Hib is incredibly effective – for example, when it was introduced in the UK in 1992, it led to a more than 90% reduction in Hib meningitis.

As high-income countries began to roll out the vaccine through the 1990s, low-income countries still had almost no access due to the cost. When Gavi was set up in 2000, it immediately began to facilitate access to the Hib vaccine.

In 2006, the World Health Organization recommended that the vaccine should be included in routine immunisations and by 2008, the vaccine had been introduced in half of all low-income countries. By 2009, 62 countries, nearly all low-income countries, had introduced Hib vaccines with Gavi support, preventing an estimated 430,000 future deaths.

3. Eliminating meningitis A

After a major global effort, meningitis A has virtually been eliminated from the African meningitis belt. The MenAfriVac campaign was rolled out across sub-Saharan Africa, and was designed to reduce infection and prevent transmission of the bacteria.

Before the vaccine was introduced, serogroup A accounted for 80–85% of meningitis epidemics in the 26 countries located in the African meningitis belt. By April 2021, 24 of these countries had conducted mass vaccine campaigns, and incidence of serogroup A meningitis had fallen by more than 99%.

4. A five-in-one vaccine is rolling out for the first time

The Men5CV (MenFive) pentavalent meningitis vaccine holds huge promise to eliminate meningitis – a major cause of neurological disease and disability – in sub-Saharan Africa. The five-in-one vaccine protects against the five serogroups responsible for almost all epidemic meningitis in sub-Saharan Africa: groups A, C, Y, W and X.

The vaccine is temperature-stable, which means it can be used easily even in remote areas with little infrastructure or refrigeration capacity. One dose confers strong protection, which is important because requiring multiple doses makes it tougher to ensure populations are fully protected.

Nigeria was the first country to roll it out in April this year, aiming to vaccinate one million children.

5. Vaccines are crucial with growing drug resistance to meningitis treatment

Antimicrobial resistance is a growing problem as bacteria and other pathogens evolve to develop resistance to treatments that could once cure a deadly illness. Treatments that were once highly effective against meningitis are starting to fail.

A study in The Lancet Regional Health – Southeast Asia found that in South-East Asia and the Pacific, antibiotics WHO recommends as first-line therapy for treating sepsis and meningitis in children and newborns are becoming less effective.

For instance, aminopenicillin and third generation cephalosporins could treat about two thirds of childhood meningitis (65% and 62%, respectively), while gentamicin could treat just a fifth (21%).

With few new antibiotics in the pipeline, preventing infections is becoming more vital than ever – and vaccines are the best way to do that.