"We could save millions of lives lost to meningitis – but we need more awareness and better funding"

The head of the Meningitis Research Foundation explains new research findings showing that tackling the disease means more awareness and more funding.

- 23 July 2024

- 9 min read

- by Priya Joi

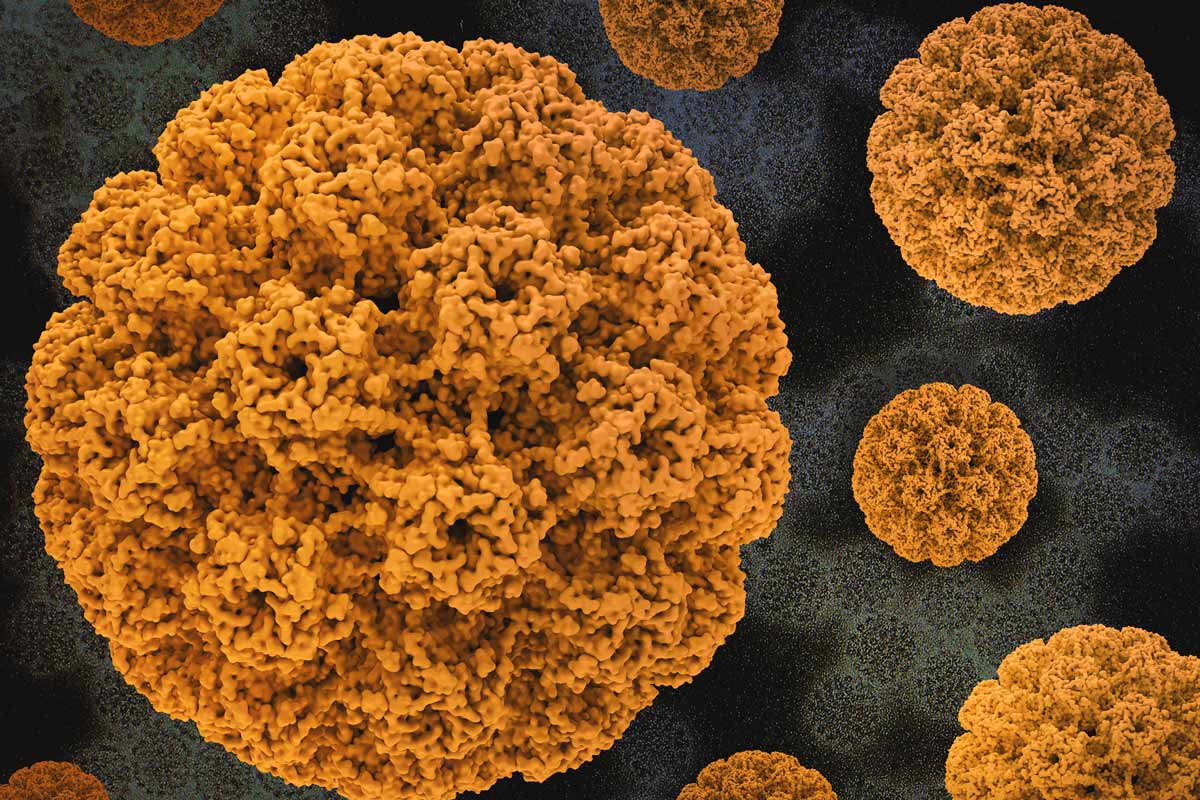

Meningitis is a condition that can be precipitated by a variety of causes, including bacteria and viruses, and it can be deadly – it killed 214,000 people in 2021. Many of these deaths could have been prevented with better awareness of the disease and the importance of being vaccinated against it. Global health players working in meningitis are now raising the profile of the disease to save lives, and the Meningitis Research Foundation (MRF), based in the UK, is one of them.

In collaboration with UNICEF, MRF published a report last month on meningitis communications challenges in Africa’s ‘meningitis belt’. VaccinesWork speaks to Meningitis Research Foundation Chief Executive Vinny Smith about the new report, progress made against meningitis and what urgently needs to be done.

Q. Can you tell us what the Meningitis Research Foundation does?

The Meningitis Research Foundation is an international charity that includes within it the Confederation of Meningitis Organisations. We were founded just over 30 years ago by a family who tragically lost their son to meningitis and wanted to raise money and invest it in research, especially at that time, for vaccines.

We are still very much connected with patients and every week we are in contact with families, trying to understand their experience in getting patients diagnosed and treated, through to their experience of aftercare, whether that's a bereavement aftercare, or whether it's living with the after-effects of the disease.

“Everyone, pretty universally, said, there's just not money here for meningitis. The reason that matters this year more than any other year is because we've got a chance to change that.”

We started out as a UK organisation, but we are now global. All the members of the Confederation are entirely independent of us – they voluntarily choose to apply to become a member – and we've now got 147 members in 56 countries around the world, and that's grown by over 30% in the last three years. In particular, we've seen huge growth in the last two years within Africa. We've now got 46 members in 20 countries across Africa.

Research is a huge part of our work, and we focus on enabling research; for instance, we are the Secretariat for the Global Meningitis Genome Partnership, which coordinates the collection and sharing of global genomic data for the leading causes of bacterial meningitis.

Advocacy is also a big part of our work, and we pushed for a global roadmap for meningitis elimination back in 2015 (it was launched by WHO in 2021) and we've been at the heart of that journey ever since. We’re on the technical task force and we co-lead with UNICEF on Pillar Five of the global roadmap, which is focused on advocacy and engagement. We are continuing to advocate for people getting the vaccines that they need, but we're also trying to advocate for good diagnosis, treatment and aftercare as well.

Q. What was the impetus for the research on meningitis communications that you undertook with UNICEF?

It was a combination of things. Our members would say that they didn't see much awareness-raising happening in their countries unless it was them doing it, nor any big national campaigns. So, we thought, if we sit in the shoes of the Ministry of Health or some of the big global players, what tools have they actually got? What resources are they given to help them do this work? And our working assumption, anecdotally, was they didn't really have much, but we didn't really have anything to anchor it in. So, with UNICEF, we spoke to people on the ground to get a sense of what meningitis communications materials they had.

Q. What were the key findings from the report?

The main finding is that there isn't enough funding for meningitis communications and outreach. Everyone, pretty universally, said, there's just not money here for meningitis. The reason that matters this year more than any other year is because we've got a chance to change that. In April, the World Health Organization published an investment case for the Global Road Map to Defeat Meningitis by 2030. Included within this is a calculation of the funding needed for advocacy and engagement (US$ 37.5 million). It could be game-changing if a proportion of these funds is used to address the gap in funding for communications and outreach activity across the meningitis belt group of countries, so communities are equipped with the knowledge that they need to prevent meningitis and to act fast when symptoms appear. Doing this could save many lives.

The second thing is that respondents stated that international health days, like World Meningitis Day on 5 October, are valuable opportunities for collective action. They can be used by civil society organisations, governments and health practitioners around the globe to share unified messages and raise awareness. More could be done to leverage these by continuing to invest in global collaboration and resources, like those created by Meningitis Research Foundation and CoMO for World Meningitis Day.

“I think we're making staggering progress, and that shouldn’t be understated.”

Another point worth making, in this age where everyone uses social media for health messaging and communications, is that it’s worth noting that radio and television really work for awareness-raising. Countries in the meningitis belt that contributed to the report told us that these work everywhere for everyone – illiteracy is high in some areas and not everyone is plugged into social media, whereas there are well-established paths for using radio and TV.

Q. It’s already been established that the awareness of meningitis signs and symptoms is low, and many people still don’t know that it's vaccine-preventable. Is that connected with the lack of communications? What are the communications challenges here?

That’s right. Even health workers sometimes say that they themselves were not fully aware of all the signs and symptoms. This, combined with the lack of information, means that even if there are vaccines available, people sometimes are just not coming forward to get them. One of the issues is that for a long time, meningitis has been seen as only an epidemic disease. And whilst that's extremely important to address, especially in the meningitis belt in Africa, over 80% of cases are not associated with an outbreak.

In addition, while the highest burden of meningitis (in terms of incidence and impact – how likely people are to die or become disabled), is without question in sub-Saharan Africa, and that's where we need to focus our efforts, the majority of meningitis in the world, by cases, is not in Africa. It's actually global.

And WHO has done a good job of reminding people that meningitis happens in every country, in every community. We’ve seen spikes in meningitis around the world, including recent events with the spread of meningitis from Umrah in Mecca back to Canada and the UK. This requires different communication to raising awareness within Africa, which is why the funding for communications is so important, to make sure that we can create the resources and tools necessary.

Q. Your report noted that the awareness that vaccines can prevent meningitis is low compared to that for other vaccine-preventable diseases. Why is this?

It’s because there is no one vaccine. The roadmap has decided, quite understandably, to focus on the bacterial causes of meningitis, the four main bacterial causes – so meningococcal, pneumococcal, Hib and group B streptococcus (GBS). For the first three, there are different types of vaccines. There isn't yet a vaccine for GBS. And even where Hib roll-out is very successful, it doesn't reach everyone in the world. So, it is a more complex web of protection from vaccines that you need to provide to prevent meningitis.

“There are over 15 million people living today with the after-effects of meningitis, including acquired hearing loss, neurological complications, and so on. We have a critical window of opportunity right now to help millions of people and save millions of lives.”

We need to get better at explaining that if people get a meningitis vaccine, even just one of them, you're still vastly more protected than if you're not going to get any of them because you've not even got a clue that you might be at risk of meningitis. As part of this research, we have developed an evidence-based messaging framework, included in the report, to start to bridge this gap. Created from the insight given by the research participants, the aim is that this framework can be used by communicators on the ground to bring greater clarity and consistency in meningitis health communications (addressing some of the issues raised in the research). It includes key messaging on meningitis, effective channels and target audiences.

Q. How do we address that complex communications challenge around the various causes of meningitis?

A good analogy could be the way we talk about cancer. There are over 200 causes of cancer that affect different parts of the body, but the essence is that regardless of the cause, all cancer is because of uncontrolled cell division. Similarly, regardless of the infectious agent, meningitis is basically inflammation of the lining of the brain (the meninges). With cancer, people might not understand uncontrolled cell division, but they most likely know about tumours, and that they make you sick – there is awareness now that if people find a lump or have unexplained pain or weight loss, they need to get it checked out. So, we need to get people to think about meningitis in the same way.

Have you read?

Q. Is one of the problems of awareness that meningitis symptoms can be confused for other diseases?

Yes, it can be frequently confused with malaria because of fever and inflammation. And the bacteria evolve so the signs and symptoms change too. For instance, in the UK in 2017, there was a rise in meningitis serogroup W cases and the symptoms didn’t look like typical meningitis symptoms of a fever – instead, infections often looked just like having an alcohol hangover. They were affecting first year university students who are often socialising a lot, and so some cases were totally missed, leading to deaths.

Q. The Global Roadmap is working to eliminate meningitis by 2030. How well are we making progress towards it, and what should we be focusing on in the coming years?

I think we're making staggering progress, and that shouldn’t be understated. Even prior to this roadmap, 300 million people have been vaccinated across 26 countries in the meningitis belt, and to have virtually eliminated meningitis A is a phenomenal achievement. This roadmap has also helped escalated progress of the new 5-in-1 meningitis vaccine, which is going to hopefully help end meningococcal meningitis epidemics.

But it won't happen if those vaccines don't reach people, and we need health systems that facilitate that. In terms of preventing new cases, there are two candidate vaccines in development for GBS which we’ve never had before, and that is a leading cause of meningitis.

The amazing thing about the roadmap is that it doesn’t just focus on preventing new cases, but advocates for support on aftercare for people and families affected. That’s important, because it's in the top six causes for acquired disability worldwide. There are over 15 million people living today with the after-effects of meningitis, including acquired hearing loss, neurological complications, and so on. We have a critical window of opportunity right now to help millions of people and save millions of lives, and as long as we get the funding, we are in a good position to do so.