From bird to cow and beyond: how H5N1 flu made the worrying leap to mammals

Some mutations that help the H5N1 influenza virus to infect mammals may already have become fixed in the viral population, a new study suggests.

- 25 April 2025

- 3 min read

- by Linda Geddes

The spillover of H5N1 bird flu to cattle can likely be traced to a single event where a bird infected a cow in Texas during mid-late 2003, genetic analysis suggests.

The virus then went undetected for around four months, transmitting to further cattle and then to various other species, including raccoons, cats and poultry. It now shows signs of permanent adaptation to mammalian hosts, the researchers said.

They stressed the need for ongoing coordination across regulatory agencies and between public and animal health organisations to improve animal health and reduce the risk of a pandemic.

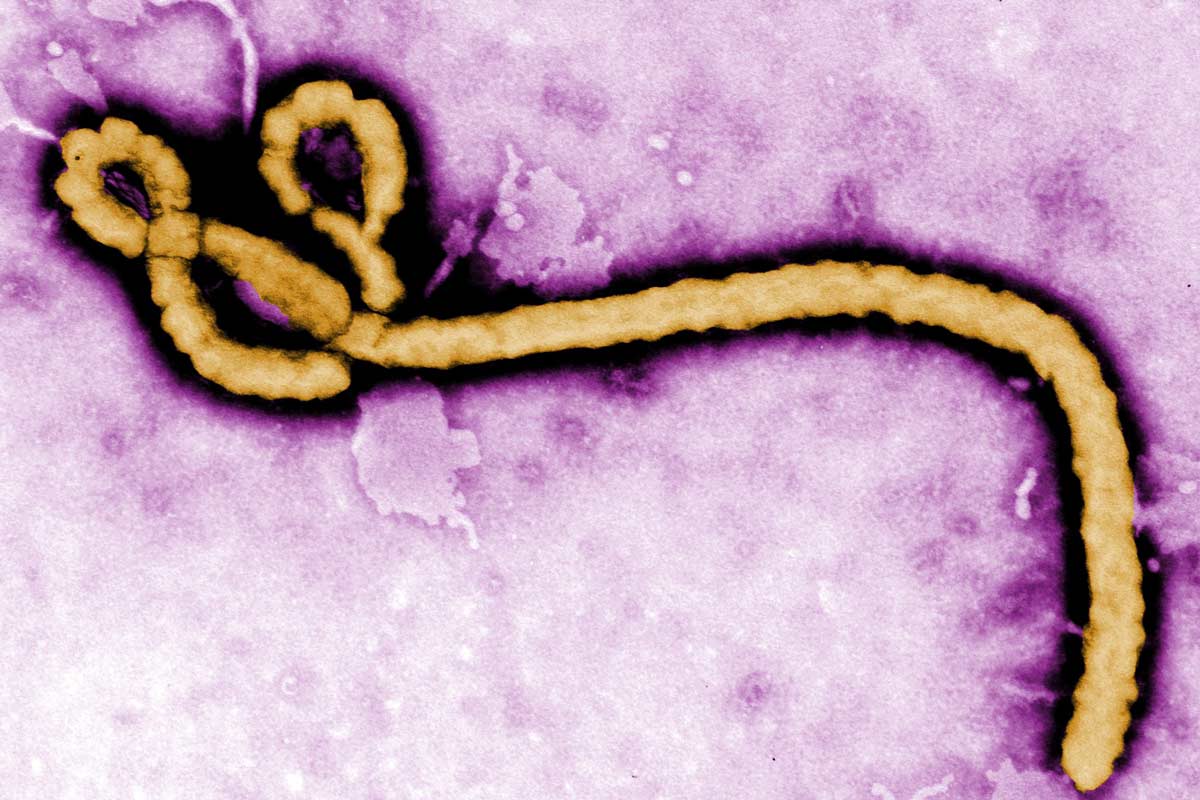

Bird flu virus

Although the H5N1 virus has been circulating in birds for several decades, a current form of the virus called 2.3.4.4b is particularly good at transmitting between wild birds and poultry, and has also been detected in various mammals, including mink, foxes, seals, otters and cats, in recent years.

The researchers discovered that the current bird flu outbreak most probably originated from a single spillover from an infected bird to a cow in Texas in mid-to-late 2023.

It has also infected a small number of humans – although there is currently no evidence of human-to-human transmission. In its latest assessment, published on 17 April 2025, the World Health Organization (WHO) assessed the global public health risk of such viruses as “low”, or “low to moderate” for those working in occupations where there’s a greater chance of being exposed to infected birds or animals.

In 2024, the 2.3.4.4b strain was identified in dairy cattle in several US states for the first time, marking an alarming and unusual expansion into a previously uncommon host.

Viral leap

To better understand how this happened, Thao-Quyen Nguyen at the United States Department of Agriculture in Ames, Iowa, and colleagues analysed genetic data from more than 100 virus variants that emerged through mixing with local bird flu strains with lower disease risk.

By combining these data with newly sequenced genomes and outbreak information from infected US dairy cattle, the researchers discovered that the current bird flu outbreak most probably originated from a single spillover from an infected bird to a cow in Texas in mid-to-late 2023.

This was followed by more than four months of undetected cow-to-cow transmission, with the movement of infected dairy cattle likely to have facilitated the rapid spread of the virus to several other states, including North Carolina, Idaho, Michigan, Ohio, Kansas and South Dakota, the researchers said.

The study, published in Science, also suggested that once established in cattle, the virus then spread to other species, including poultry, raccoons, cats, and wild birds such as grackles, blackbirds and pigeons.

Genetic analysis of the virus also revealed mutations linked to mammalian adaptation – some of which have already become fixed in the viral population. “This result likely reflects the [roughly] four months of evolution in dairy cattle,” Nguyen and colleagues said.

“The potential remains for these viruses to acquire other genetic markers that mediate the probability of transmission in mammalian hosts.”

Have you read?

Pandemic threat

Its continued persistence in US cattle, and evidence of cattle-to-human transmission poses a pandemic threat, the researchers added, and called for a One Health approach to reduce the risk of this happening.

This includes improved surveillance of cattle and other agricultural animals, alongside better support for passive surveillance of wild mammals and birds.

“Our study demonstrates that [influenza A virus] is a transboundary pathogen that requires coordination across regulatory agencies and between animal and public health organizations to improve the health of hosts and reduce pandemic risk,” they said.