Cholera and the inequitable origins of public health diplomacy

The arrival of cholera on European shores in the 19th Century helped kick off the long path towards modern global health institutions and diplomacy. However, these beginnings were anything but fair.

- 22 September 2021

- 7 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

The world shrinks, a terrible new sickness spreads

It’s hard to say exactly how long cholera has been among us. Maybe the ‘stomach-parching' vomiting disease that the Portuguese historian Gaspar Correa saw in India in 1543 and recorded as “moryxy” was an early outbreak. What’s clear is that in the 19th century it flared out of obscurity. Before long, it had changed the way the West sought to govern disease.

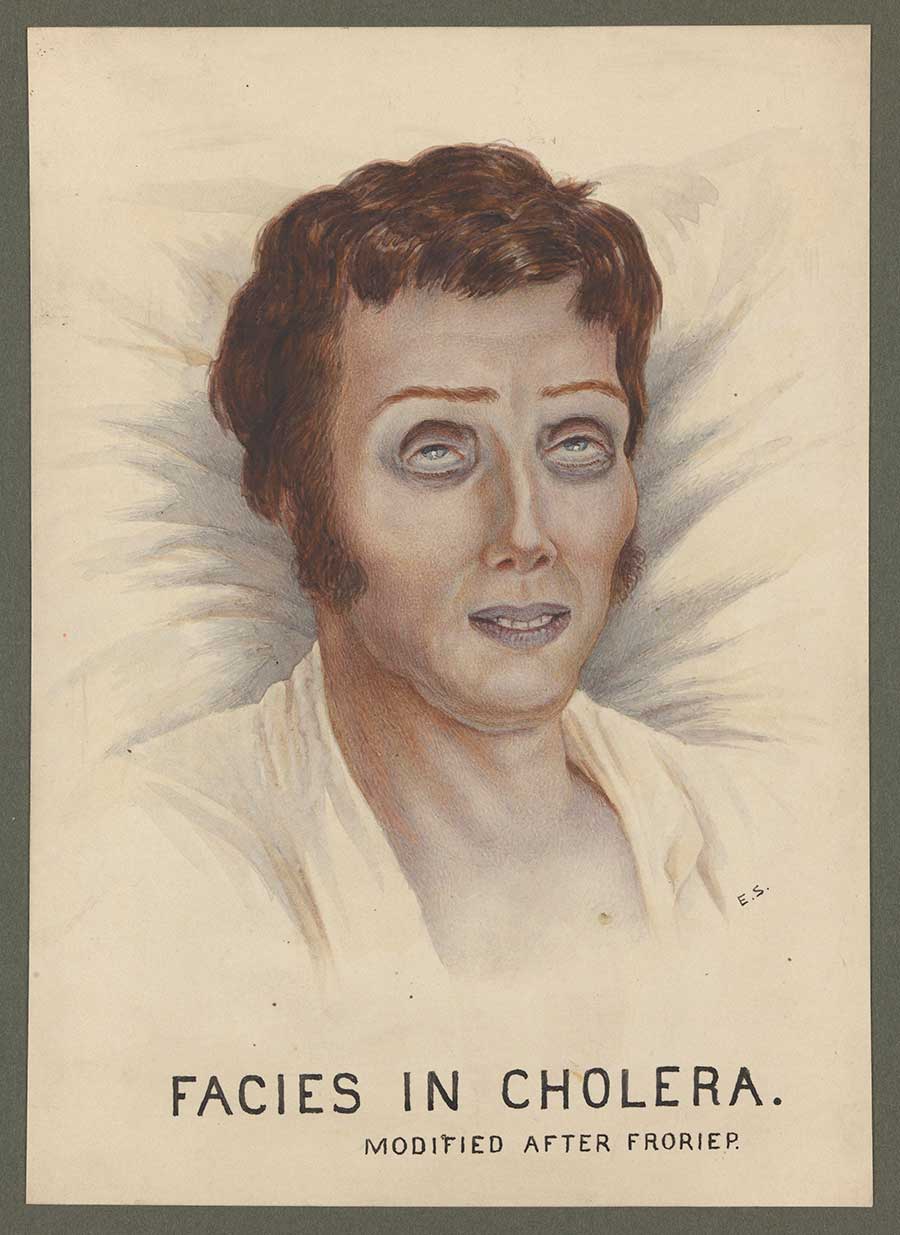

Credit: Wellcome Collection

An 1817 epidemic saw the Indian subcontinent overrun. The infected suffered bouts of watery diarrhoea and vomiting, leading to cramping and dehydration; the sickest died in hours. It spread fast, and far: in 1820, it hit modern-day Myanmar and Sri Lanka; soon it killed 100,000 in Indonesia and was reported in the Philippines. The following year it reached the Persian Gulf, Turkey, Syria and southern Russia. Then it ebbed.

While cholera caused many more deaths in other parts of the world, its risk was considered in terms of European lives and European profits.

To Europe, it was an “Oriental” scourge until it arrived on its own shores. In 1829, a second pandemic sprang up – again, probably in India – quickly fanning out along busy trade and military routes, reaching Moscow in 1830. Over the course of the following year it spread across northern Europe, rooting in London in the spring of 1831. From England, it moved into France, killing 21,000 in Paris in 1832. Within a year or so, it had cut a swathe across America.

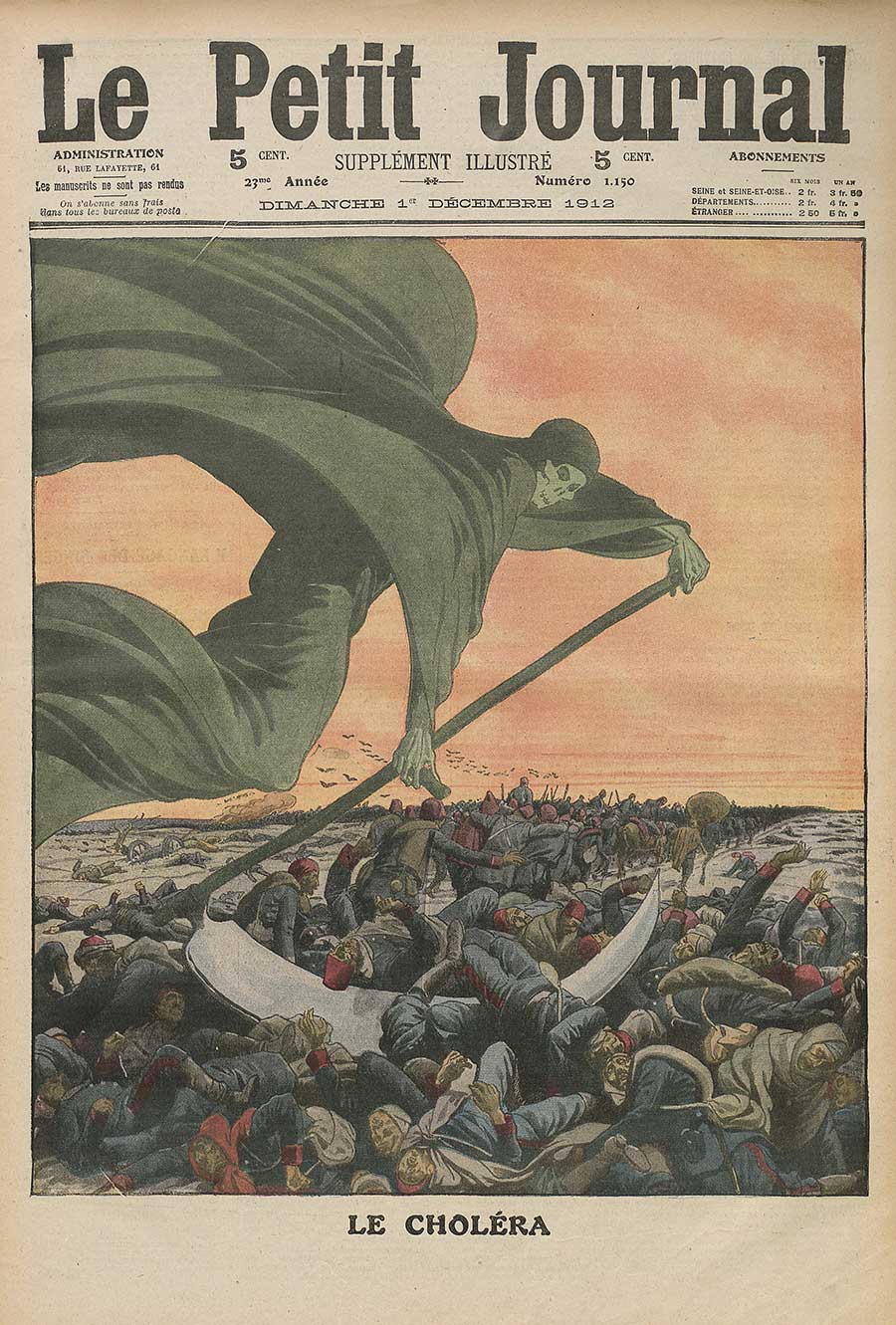

A third pandemic, which rippled across the globe through most of the 1850s, was even more devastating. We are living, now, amid the seventh, which continues to infect 3-5 million people each year.

It was not lost on 19th century onlookers that these terrifying, continent-crossing outbreaks were a function of their era: the world was shrinking. New technologies of transit and the economic pathways of imperial extraction had brought distant landmasses together. Contagion was not well understood – in fact, until the later part of the century, germ theory was overshadowed by “miasma theory” as the most popular explanation for the spread of disease – but it was clear enough that sickness often travelled along the same routes that carried goods and people.

A diplomatic remedy?

Goods and people were travelling in greater volumes than ever before and in Europe the pressure to facilitate shipping and enable fluid linkages across borders turned the 19th century into a period of nascent “internationalism.” There were conferences for the standardisation of weights and measures, summits for the harmonisation of postal relations, bilateral conventions about time and about money.

It was in this context – a moment of twinned political excitement and anxiety about thinning frontiers, which could act as gateways to both economic abundance and to sickness – that public health first found explicit recognition as a question demanding international collaboration.

Have you read?

The inaugural International Sanitary Conference – the first in a sequence of fourteen – was convened in Paris in 1851 with the aim of harmonising maritime quarantine requirements. Discordant policies were a costly inconvenience, but so were outbreaks. Reaching an agreement would, in the words of the President of the Conference, render “important services to the trade and shipping of the Mediterranean, while at the same time safeguarding the public health”. Its achievements were slight: no widespread commitment was reached. Seven subsequent Conferences would make quarantine, and the threat of cholera to health, trade and governance, their focus.

“Fortress Europe”

In pioneering diplomacy for disease control, these Conferences were foundational to modern international cooperation for public health; according to a 1975 book published by the World Health Organization, they led “almost a century later, to the founding of WHO.” But far from articulating health in terms of equity and universal rights, as WHO does today, the character of the summits was resolutely Eurocentric, explicitly geopolitical.

Though agendas varied from summit to summit, the notion that the “public health” to be “safeguarded” was a European one was never substantially in question. Cholera – pointedly termed “Asiatic Cholera”– was cast as an invader from the East. As such, Eastern European countries were figured as the frontline. One delegate at the 1851 meeting hoped that Russia would “find it worthy of her greatness to accept, against Asiatic cholera, the noble role that Austria has fulfilled for a long time against the Oriental plague”, “at the very moment when, thanks to the railway, the borders of the different states of Europe crumble.”

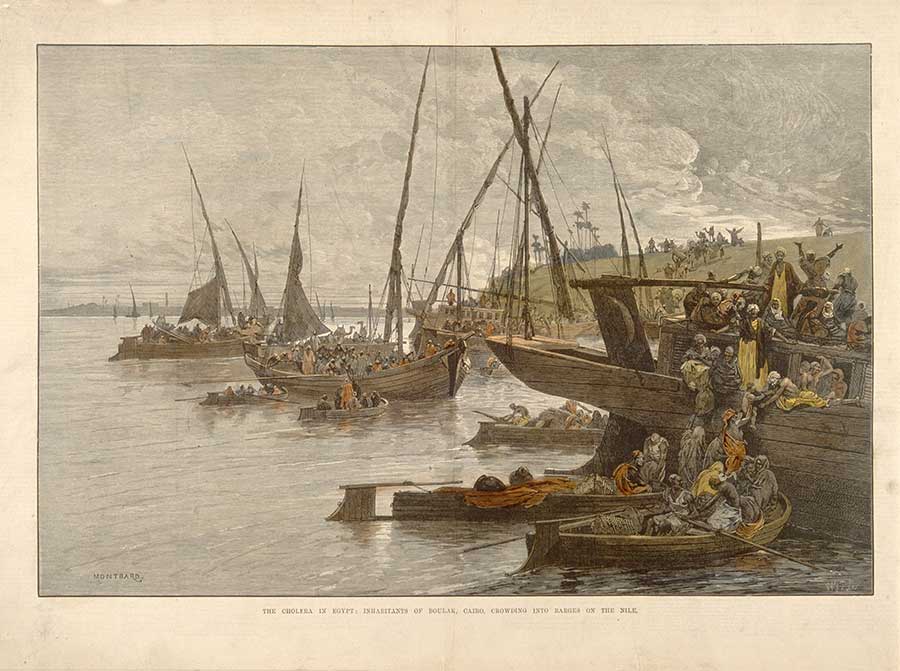

The tactical map of “Fortress Europe” changed with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, which would rapidly become the conduit for a tremendous share of European – particularly British - shipping. Egypt’s strategic importance swelled. “It is not in Europe that one has to await cholera to combat it,” one delegate said at the 1894 conference. “It is afar, on the roads that it usually follows, where it matters to block its passage.”

The protection of the Egyptian people and other ‘Orientals’ mattered – but only in as much as Egyptian public health buffered Europe. And while cholera caused many more deaths in other parts of the world, its risk was considered in terms of European lives and European profits. At the 1892 conference in Venice, Boutros Pacha, the Egyptian delegate, protested: “You make of Egypt a sentry to safeguard Europe, and then you tell her “Pay for it!”

The “unsanitary Orient” and politically expedient racism

The standardisation of quarantine for European ships proved difficult to resolve, hamstrung by delegates’ doubts about contagion theory (if cholera wasn’t contagious, quarantine wouldn’t help), and, very often, by strident British opposition to a measure which risked severely impacting the maritime empire’s bottom line. Easier, by far, in the words of historian Benoît Pouget, to “externalise [quarantine measures] to the East”.

In 1865, cholera travelled to the Eastern Mediterranean from the south, along a Hajj pilgrimage route from Africa. Already cast as a dubious figure in European public health discourse, the Asian or African pilgrim became a focal point for disease containment.

“Medical experts, missionaries and British authorities blamed Hindu and Muslim pilgrims by framing cholera within an Orientalist discourse known as “miasma,”” writes historian Stephanie Anne Boyle. Miasma theory, she goes on, “asserted with great certainty that the East existed in a filthy timeless space with no knowledge or concern for modern scientific and social practices.”

By the Conferences of the 1890s, germ theory was better established - miasma theory less well-accepted - but the scapegoating of other races carried on. Valeska Huber writes, “the suspicious border-crosser par excellence was the Muslim pilgrim,” quoting an 1892 Times of India article: “The actual danger for Europe lies in the international Mahomedan places of pilgrimage… Oriental squalor and the absence of any, or any serious sanitary police… encourage the disease whose germ finds a fertile soil in the bodies of the pilgrims, weakened by all kinds of deprivations.”

Though the 1892 Conference elaborated a series of workarounds for ships passing the Suez – including disinfection and a risk classification system based on, among other measures, the telegraphed reporting of a ship’s status – pilgrim vessels were understood to be suspect in all cases. At the 1894 Conference, it was reasserted: “The Mecca pilgrims must be subjected to quarantine in the lazaretto of Camaran. This measure will undoubtedly reduce the danger of the introduction of cholera.”

A network of lazarettos – isolation wards – was established along the Red Sea; its administration passed into the hands of an Alexandrian Health Council manned by European officers. Similar measures were instituted to block an “epidemic highway” in the Persian Gulf – “meant also to ensure the health security of the Indian route,” according to Pouget. A standard international approach to public health appeared, at last, to be resolving. Under its gaze, Asians, Africans, Middle Easterners, migrants and pilgrims were vectors of disease, not a global public worthy of equal protection.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you