Greetings from the North Pole to the Polarised North: street art Santa arrives in Germany

An expression of frustration with vaccine skeptics, German street artist and former immunologist Lapiz's new work is not your typical Christmas card.

- 22 December 2021

- 1 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

Towards the end of the October of this second plague year, hospital wards in Germany began to fill rapidly with gravely ill COVID-19 patients. By late November, almost as many people were dying every day as had died each day in the vaccine-less November 2020, a kind of trick symmetry made arguably more frustrating by reports from ICU staff that 90 percent of the dying were still unvaccinated. To many, including the street artist Lapiz, that fact rang as an indictment: the victims had had the choice, and they had opted for personal vulnerability and its corollary, collective risk.

"A minority of disbelievers is taking the society hostage. This is not a painting of schadenfreude but of anger, it shows the Christmas that many of these disbelievers are facing for a final time.”

TV reports showed the busy, bundled forms of ICU nurses, obscured under layers of PPE, photos of their friendly faces taped to their aprons – the uncanny compromise between sterility and human connection.

“Horrific,” thought Lapiz, imagining waking up in the emergency room surrounded by printed-out smiles. A storm-front of feeling – rage, underscored by “complete disbelief, and sadness, really,” – rolled in, carrying with it the idea for a new artwork. He worked quickly, jettisoning his typically methodical creative habits, chasing intuition instead.

On the dark early morning of December 6 – St Nicholas Day, on which many German kids would wake to find their boots magically filled with Christmas candy; a coincidence of timing, he says – Lapiz set out to paste up the new work in four locations around Hamburg’s Messehallen, the convention centre that had served as the city’s central vaccination site. (“[It’s] currently closed due to lack of demand,” Lapiz wrote me in an email.)

The sun was rising by the time he finished, and people were emerging from their homes, which made him nervous, because right then, in the street, in the flesh, he didn’t feel like having the heated conversations the piece was intended to provoke.

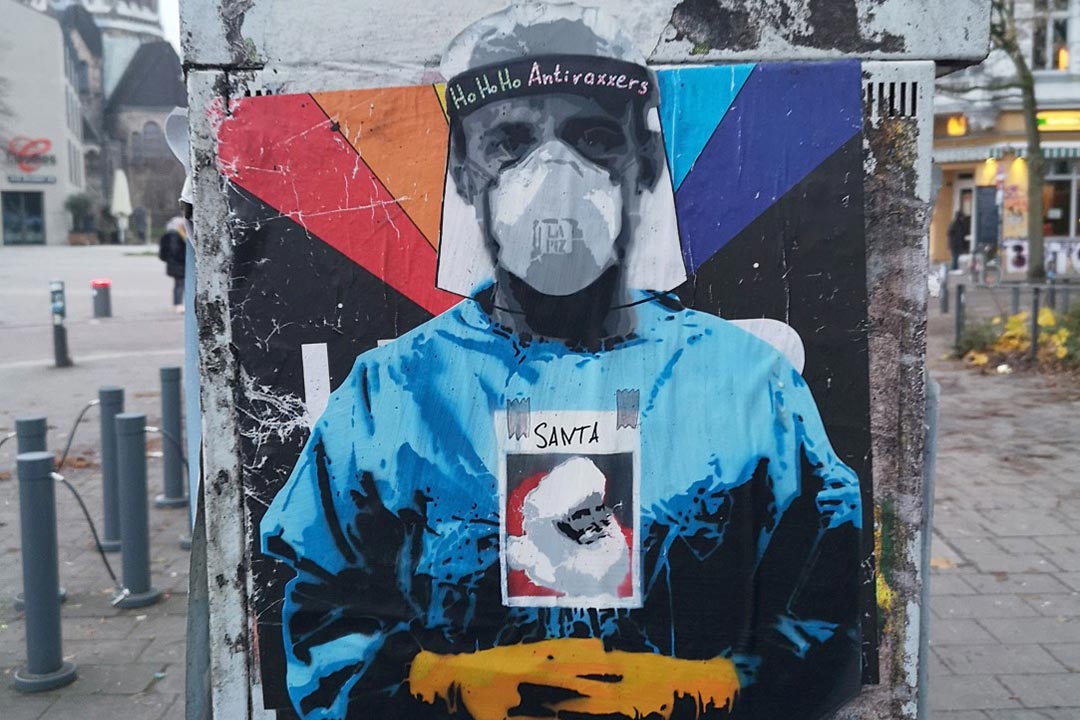

Lapiz’s new work, entitled Ho Ho Ho Antivaxxers, is a jolt: ironic, bitter. A health-worker in blue PPE, yellow-gloved hands folded in resignation, or maybe disapproval, gazes glazed-eyed out through a face-shield, unrecognisable behind a bulky N95 mask. A polaroid of his face is taped to his Tyvek-covered chest though, revealing him as white-bearded, apple-cheeked, bespectacled, and dressed in a red fur-lined hat. He’s Santa Claus. Merry Christmas.

Three days later, aboard a train to his dad’s home, Lapiz posted the new work to Instagram. In the caption, he made his frustrations explicit: “in Germany, it is the new normality that individuals who are in need of surgery are now turned away because there is not enough space. A minority of disbelievers is taking the society hostage.” He went on. “This is not a painting of schadenfreude but of anger, it shows the Christmas that many of these disbelievers are facing for a final time.”

Have you read?

The backlash was swift. Internet strangers and real-life acquaintances accused Lapiz of inciting hatred against people too anxious to get vaccinated; of being either a stooge or a dupe of Big Pharma. (“Big Pharma is probably not the best people in the world,” Lapiz told me, “but it doesn’t mean the vaccine is bullshit,”) Angry people – Lapiz among them – slung scornful epithets. Reeling a little from the spiral of aggression, he shut down the comments section. “This is not the place to have this kind of conversation,” Lapiz wrote, inviting responses in the hopefully more measured and accountable space of his DMs instead.

When we caught up a week later, Lapiz seemed still a little bruised, a little confused by the fallout from his latest public art provocation. He told me that he – a former scientist with an immunology PhD – had retreated to PubMed, an online index of biomedical and life sciences journal articles, in the days after the Ho Ho Ho comment-section implosion, and searched “COVID-19 vaccines”. More than 14,000 pieces of scientific investigation arrived at his fingertips.

There was a vague practical purpose to his search: it would be good to be able to cite the research directly in future discussions with the vaccine-sceptical people he might encounter, he thought. But it seemed to me that PubMed’s library of research also offered an emotional refuge – that the crisp language of evidence and reason represented an antidote to the dizzying forces of cultural sectarianism.

“I feel like I cannot relate to them at all,” Lapiz said of the voices of ideological science-scepticism that appear to constitute a sizable and persistent chunk of Germany’s population: 70.4% of the country is double-vaccinated at the time of writing, a sub-par turnout compared to Portugal at 89%, or Spain at 78%.

It’s a shock. Before COVID-19 Lapiz imagined anti-vaxxers as an eccentric fringe, not a quorum-shattering critical minority. “It’s ridiculous,” he said. “It took a year to make this amazing thing, and now we have it, at least in the most privileged part of the world, and people don’t take it. I would never have guessed it would be a problem.”

That rupture of expectation equates to a profound disconnection. “If you want to argue with someone, if you want to discuss with someone, you have to be able to relate to them, you have to understand where they are coming from, put yourself in their shoes – like, understand why they are afraid. And I can’t, because I have all this scientific data.”

“It freaks me out,” he says. “This is the society I live in.” Last week, he watched a demonstration of 1,000 “disbelievers” march by, streets away, in Hamburg, not in the right-wing strongholds of antivax agitation. “There are so many people not getting vaccinated, who will not change, which means that the situation will not change at all in the next years. And it freaks me out that I cannot talk to them at all. I have no idea how to reach them.”

The good news is he doesn’t have to – not directly, at least. Lapiz has realised he may not be the best interlocutor, being personally positioned too far away from the "other side" – too allergic to ill-founded argument and conspiracy-theory discursive tropes.

But the art, in its kaleidoscopically subjective way, does its own talking, its own reaching out. “I don’t necessarily want to be the person in that discussion,” he says, “but I think that the discussion is still important.” Three of his four Santas are still up, still poking at passing consciences. The fourth is gone, destroyed by way of rebuttal. I ask him whether he’ll replace it. He says no – that, he thinks, would feel a little shrill.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you