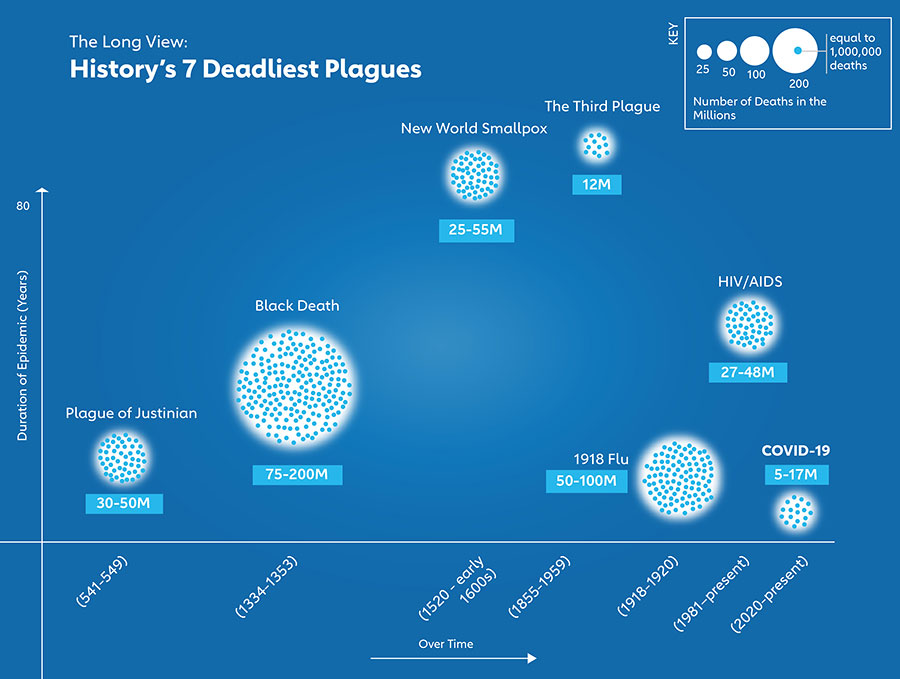

History’s Seven Deadliest Plagues

SARS-CoV-2 has officially claimed 5 million lives, but credible estimates place the pandemic’s true death toll closer to 17 million. Either count secures COVID-19’s position on our list of history’s deadliest plagues.

- 15 November 2021

- 8 min read

- by Maya Prabhu , Jessica Gergen

In early April 2020, when COVID-19 was beginning to seem inescapable, the Nobel Prize-winning economist and psychologist Daniel Kahneman, a scholar of the way we make judgements, spoke to a New Yorker podcast.

"This is an exponential event," he said. "That is, we see things doubling every two days, every three days, every four days, and people – certainly including myself – don’t seem to be able to think straight about exponential growth.”

That the deaths of today represented infections of maybe four or five weeks ago, even as the infection rate was whizzing skywards on an exponential trajectory, was “beyond intuitive human comprehension. And that’s interesting: that we’re in a situation that we’re simply not equipped to understand.”

At that time, the confirmed global death toll from COVID-19 stood at 80,000. This month, the official body-count stands at 5 million – a number understood to represent a major underestimate. Some credible analyses peg SARS-CoV-2 fatalities at closer to 17 million. This number places it firmly on the list of the deadliest pandemics in history, even though it has run for a far shorter time than others on the list.

Is it simpler to grasp a number of such an extraordinary scale than the dynamic swing of exponential growth? Perhaps. Still, at such great heights, our tallied casualties tend to take on the anaesthetic gloss of statistical abstraction. Easier, maybe, to comprehend the pandemic’s losses at smaller scale, in images: refrigerated mortuary spill-over trucks in New York, parking lots full of funeral pyres in India’s national capital region.

Another way of drawing significance from the grim statistic is by comparison. COVID-19 already ranks among the world’s deadliest epidemics, each of which can claim credit for epochal – not just generational – shifts. Granted, absolute figures tell you only so much: COVID-19 arrived on a far more populous planet than the one which was devastated by the Black Death. But it remains clear that such a massive loss of life is bound to change the world.

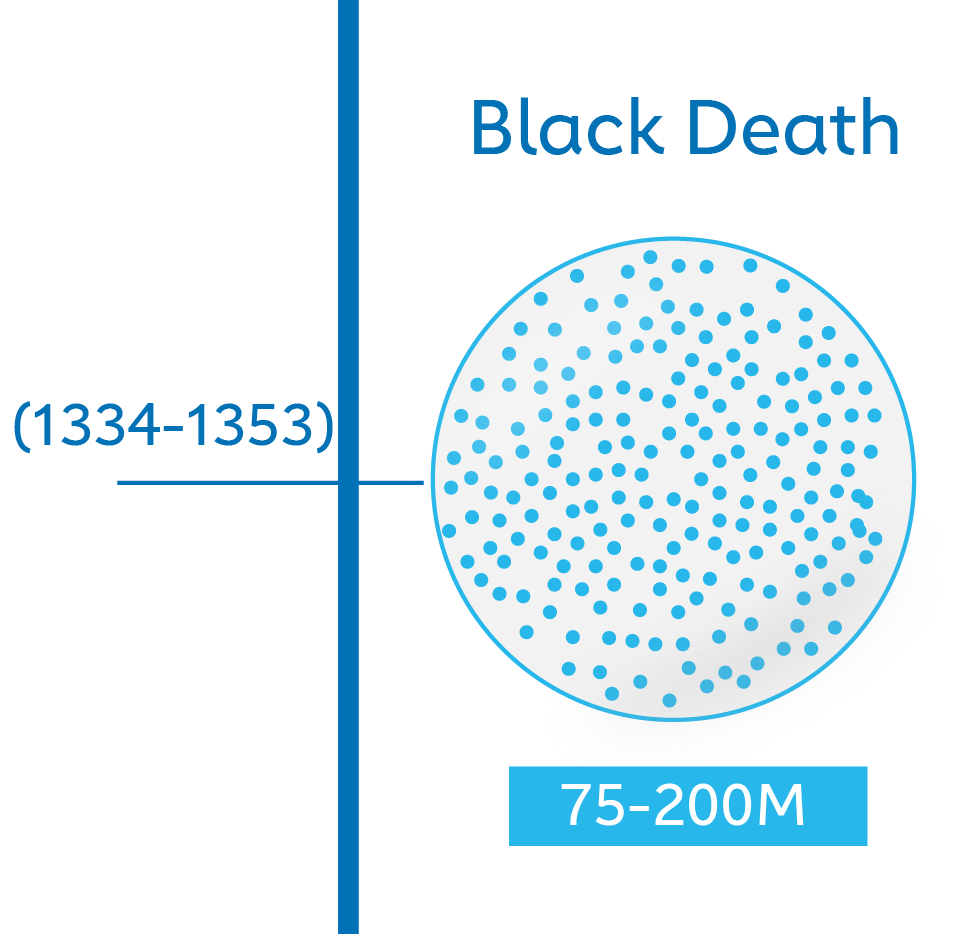

Black Death: 75-200M (1334-1353)

The second pandemic of the bubonic plague likely sprang up in north-eastern China, killing maybe five million, fast. It moved west, through India, Syria and Mesopotamia. In 1346 it struck a trading port called Kaffa in the Black Sea. Ships from departing Kaffa carried trade goods and also carried rats, who carried fleas, who carried Yersinia Pestis. In October 1347, 12 such ships docked at Messina in Sicily, their hulls full of dead and dying sailors. By the time harbour authorities realised what the ships brought, it was too late. Over the next five years, the Black Death killed almost half of Europe.

Panic stirred a fervour for scapegoating, and anti-Semitic pogroms tailed the advance of the epidemic. In some towns, the Jewish populations were completely annihilated; other towns, like Marseilles, gained reputations as safe-havens - the social reality of Europe was reordered as its population tanked. Briefly, wars halted and trade slumped. Crop-land went to seed. Wages rose with the intensified demand for labour, and chinks of opportunity for real social change opened up. Kings and queens and archbishops died. The incandescent Sienese art school was extinguished after too many luminaries were lost.

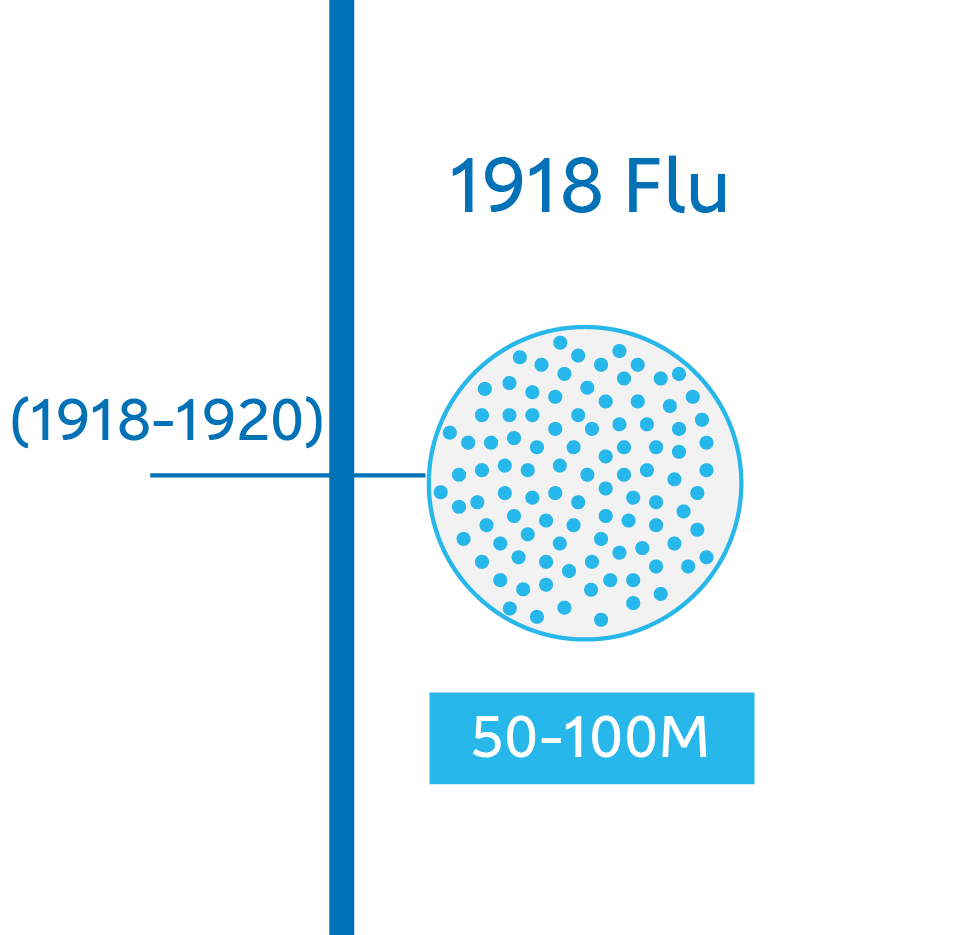

1918 flu: 50-100 million (1918-1920)

Five days after the pandemic influenza of 1918 made landfall at Brevig Mission, a remote village in Alaska, 90 percent of the community was dead. In Philadelphia, priests collected corpses in horse-drawn carts. In parts of India the devastation was so complete that bodies were left out for the jackals to pick at.

It arrived in Bombay in June 1918 on troop ships returning soldiers from the battlegrounds of World War I and, by year’s end, had claimed possibly as many as 18.5 million lives in South Asia. Freetown, Sierra Leone, lost four percent of its population in three weeks. Persia may have lost as many as 22 percent of its people. 50 to 100 million people the world over died before rising immunity blunted the virus’s threat.

Unlike COVID-19, which is deadliest for the elderly, half of the influenza’s casualties were young - in their 20s and 30s. In fact, in his book The Great Influenza, historian John M. Barry projects that as many as 8-10 percent of all young adults may have been taken out during the 2-year surge of the virus. The economic effects of the shock to the workforce were sharp and various. In parts of the US, manufacturing output declined by 50 percent. With croplands empty of labour, food production stalled in Africa; famine or near-famine followed in many places. In India, where the British overlords in their spacious homes remained markedly safer than the local population, the cruel inequities of the epidemic may have added fuel to an incipient revolutionary fire.

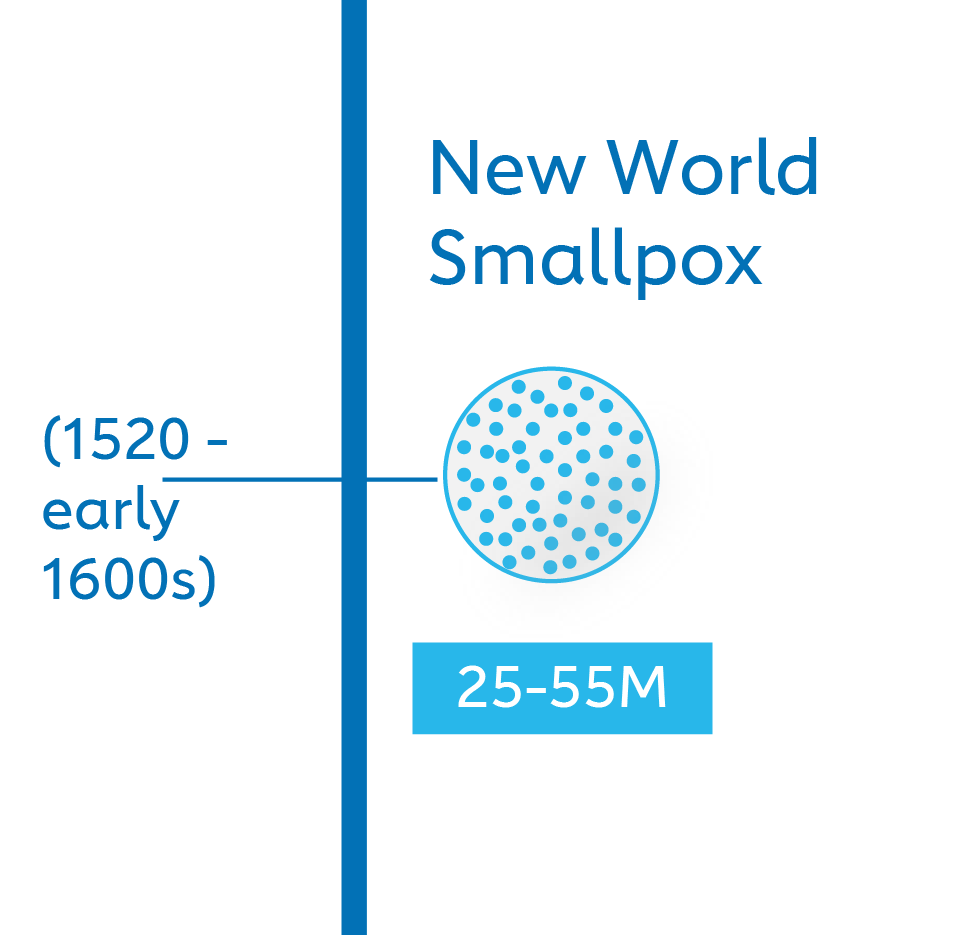

New World Smallpox: 25-56 million (1520 – early 1600s)

Smallpox had been a familiar scourge in many parts of the world for centuries when the first Europeans arrived on American shores. 20-60% of those it infected in Europe died. Survivors emerged immune.

But the pre-Columbian indigenous people of America were immunologically naïve to the variolavirus that landed aboard a Spanish ship at present-day Veracruz, Mexico in April 1520, hidden in the body of an infected, enslaved African man. The continent was perfectly vulnerable.

The outbreak seeded by first contact was catastrophic, but it was only the first volley. Waves of infection broke on the continent for decades. Whoever didn’t die of smallpox was killed by the imported influenza that chased the smallpox or the measles epidemic that surged in its wake. A mind-blowing 90 percent of the indigenous population perished. Great civilisations and their cultures were snuffed out suddenly, clearing the path for European colonisation. The “Great Dying” had a planetary impact: researchers believe that the massive abandonment of farmland to nature in the wake of this great wave of infection and death may have caused the global climate to cool in the 1600s.

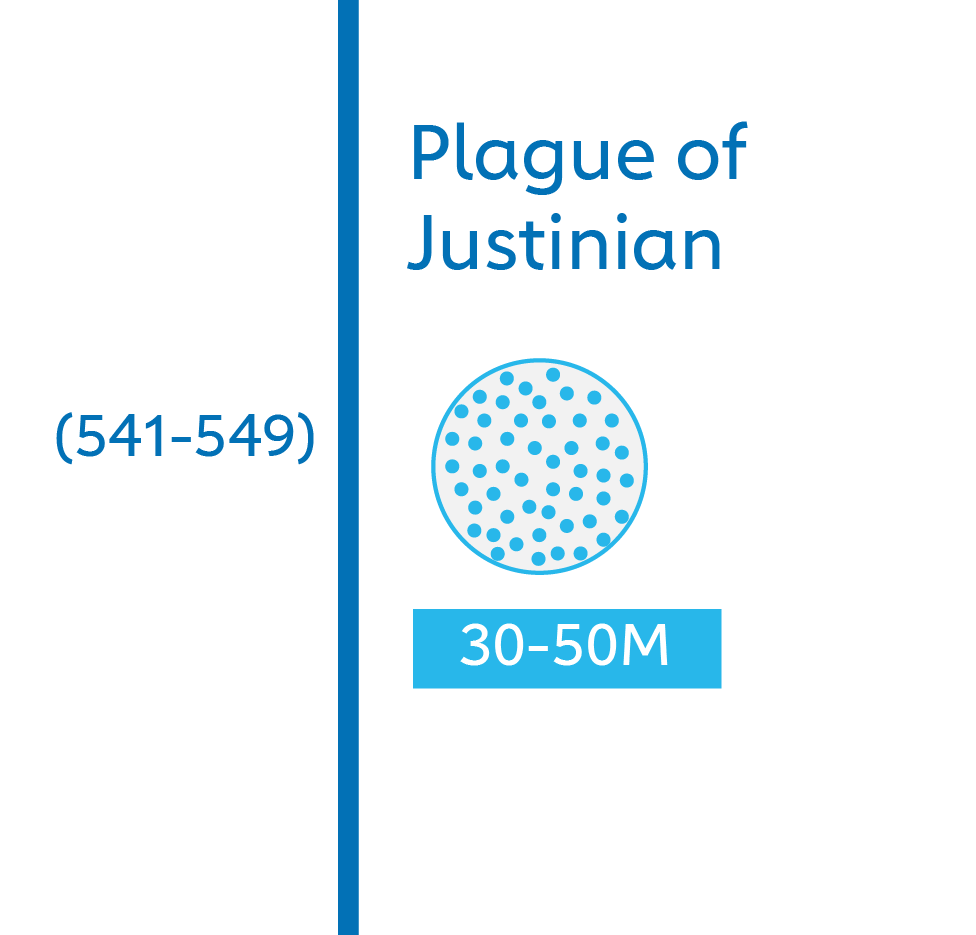

Plague of Justinian: 30-50 million people (541-549)

The disease – now confirmed to be bubonic plague – reached Constantinople, capital of the Late Roman or Byzantine Empire, in 541 AD. It was soon killing 10,000 people a day. Corpses littered public spaces and were stacked like produce indoors. It was perhaps the first major outbreak of bubonic plague the world had seen and the record suggests that it extended across continents, reaching Roman Egypt, the Mediterranean, Northern Europe and the Arabian Peninsula. Recent scholarship analysing scientific findings alongside textual and numismatic records points to the possibility that it may have left an even further-reaching imprint on the early medieval world than previously understood.

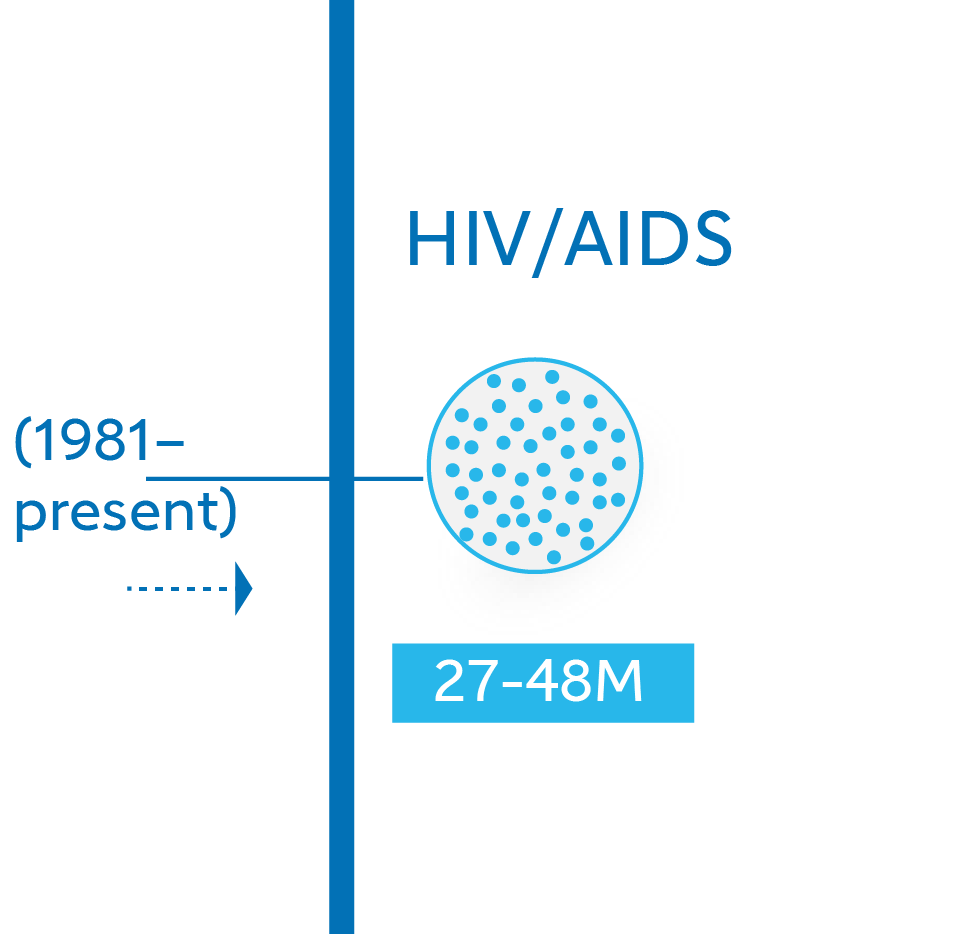

HIV/AIDS: 27.2-47.8 million (1981 – current)

The HIV virus may have first crossed over from chimpanzees to humans in the Democratic Republic of the Congo via blood contact around 1920. It spread more-or-less undetected until 1981, when a virulent pneumonia and rare cancer called Kaposi’s Sarcoma began to crop up among gay men in the US. By year’s end, there were 270 reported cases. 121 of them had already died.

It’s possible, however, that by 1980, HIV was already on five continents, infecting between 100,000 and 300,000 people. By 1987, when the WHO launched the Global Program on AIDS, an estimated 5-10 million people worldwide were living with HIV. Today, despite massive advances in the treatment and management of HIV, it remains incurable. The number of people infected stands at around 38 million, with more than two-thirds of those patients living in Sub-Saharan Africa. UNAIDS estimates that 36.3 million people have died of AIDS-related illness – but with improved medicines and improved equitable access to those drugs annual AIDS-related fatalities have declined 47% since 2010.

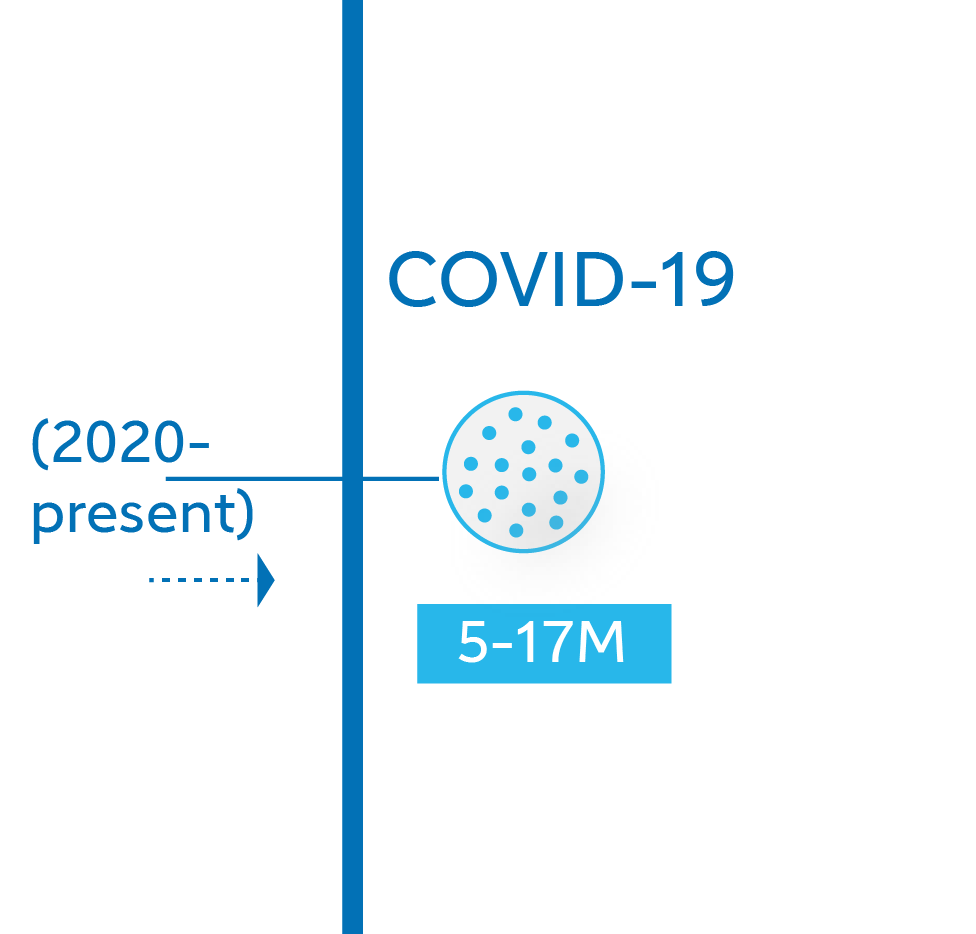

COVID-19: 5-17 million (2020 – current)

You probably know this one: in December 2019, a series of unusual pneumonia cases cropped up in Wuhan, China. At first, health officials offered reassurance: the new coronavirus wasn’t being passed from human to human. That quickly proved false. In late January 2020, the WHO declared COVID-19 a global health emergency. By March, there were cases in 114 countries. Nations around the world cascaded into lockdown. A year and a half later, 17 million people are estimated to have died; many survivors have lingering symptoms. The risks of the pandemic – of the social and economic disruptions, the psychological toll on healthcare workers across the world, the deepening global inequality due to uneven vaccine access – are still resolving.

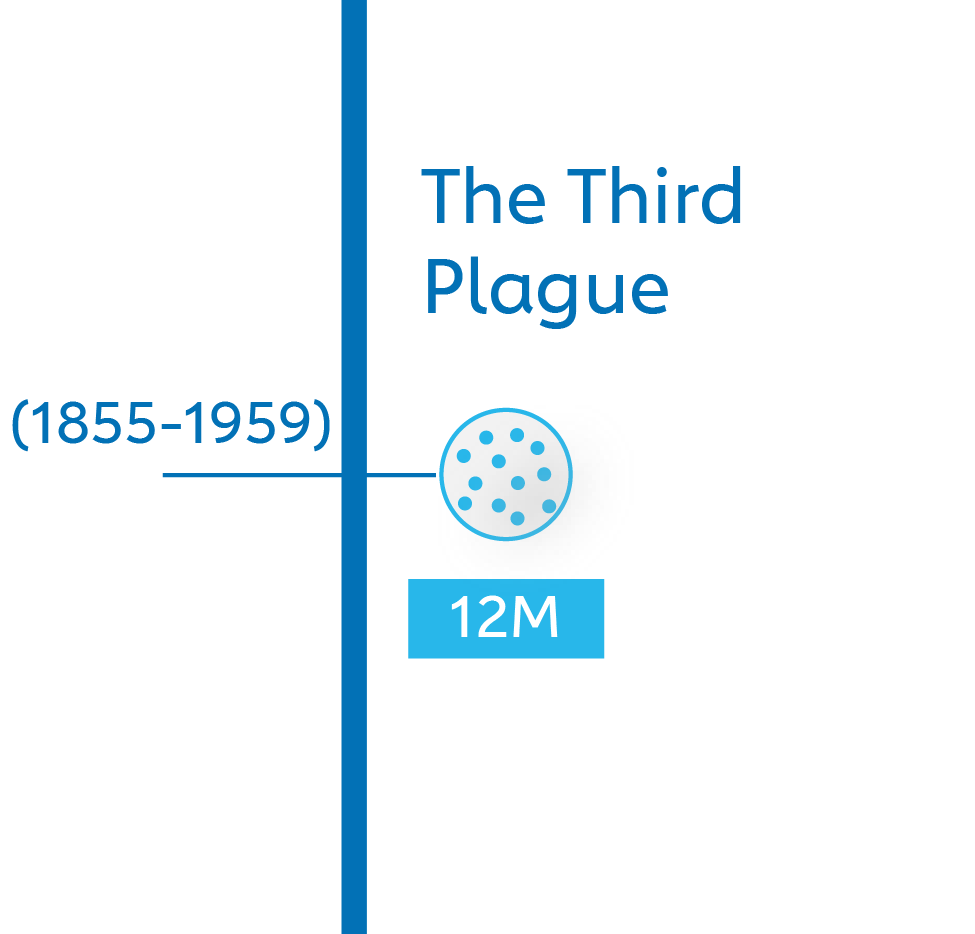

The Third Plague: 12 million (1855 – 1959)

It had never completely gone away, but the bubonic plague resurged violently in 1855. Beginning in Yunnan, China, it spread to the port cities of Guangzhou and Hong Kong by 1894. Outbound ships seeded burgeoning clusters in Bombay, Calcutta, Cape Town and San Francisco by the turn of the century. It didn’t stop there: before 1959, some 12 million people across the world – half of them in India – would be dead.

But science was catching up, meaning that this would be the final pandemic of the bubonic plague. The causative bacterium, Yersinia pestis, was identified in 1894 in Hong Kong. The observation that a litter of dead rats in the streets often preceded an outbreak finally drew scientists to the bacterium’s vehicle: rat fleas, who infected humans when their first hosts died. Rat-proofing measures and insecticides helped preventively. The discovery of effective treatments (sulphonamides, beginning in the 1930s, and antibiotics like streptomycin from 1947) would finally tame the deadliest epidemic disease the world has yet known.