International Women’s Day: Caring for Everyone: an ASHA worker’s COVID-19 story

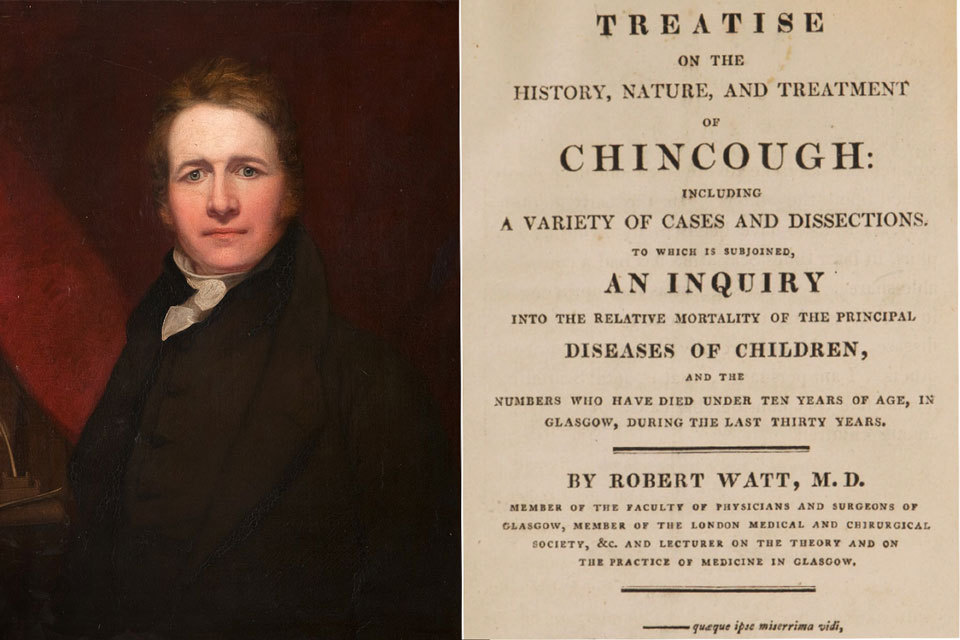

This International Women’s Day Vaccines Work is hosting a series of interviews with inspirational women from across the world. Here Rathnamma P, an 'ASHA' in Bengaluru, India, explains how the country's army of one million female community health workers has helped carry the country through the first year of the coronavirus pandemic.

- 8 March 2021

- 6 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

Follow along: #ChooseToChallenge #IWD2021

The first case of COVID-19 at the primary healthcare centre of Anekal, a patchwork district of tech-parks and old villages at the southern extent of Bengaluru’s urban sprawl, in southern India, defied anxious anticipation for months. It came, at last, on 26 June 2020 – Rathnamma P recalls the date without having to think about it.

Before COVID, our work majorly focused on pregnant women and children. Now, after COVID, we are caring for everyone – the entire village, the entire taluk, the entire district.

A second patient tested positive four days later, she remembers. But soon, “as more and more people started traveling, when the buses started, people started going to their workplaces,” the local infection rate gathered pace. News of positive tests stopped registering as landmarks. India’s COVID-19 epidemic galloped towards its September peak, with more than 90,000 new cases each day. In Anekal, Rathnamma’ days grew longer.

Rathna, as she is known, is part of India’s million-woman army of Accredited Social Health Activists, or ASHAs, last-mile health workers recruited from the community they serve, who often represent the crucial, capillary link between a far-flung village or urban slum and the state’s organs of healthcare. Since 2005, when the programme was introduced, India’s ASHAs have been instrumental in deepening childhood immunisation coverage, encouraging pregnant people to opt for safer in-hospital births, carrying out door-to-door health surveys, looking after the needs of long-term tuberculosis and leprosy patients, and more. In 2020, Rathna, a 43-year-old with two almost-adult children, was entering her tenth year on the job. The work was gratifying, its challenges familiar. Then, in late March, the pandemic made landfall in India, and the ground shifted beneath her feet.

The two-month national lockdown, rated one of the most stringent in the world, cleared neighbourhood streets overnight. Fear – of the virus on the one hand, and the police crackdown on the other – kept most Indians in their homes, while fear of hunger forced tens of thousands of poor migrant labourers to flout restrictions and head towards their villages on foot.

“The only people who walked around boldly during lockdown was us,” says Rathna. There were cautious voices who urged her against heading out to work in the edgy climate that Spring, but her own family understood. And so did the local police: “nobody stopped us from going anywhere,” Rathna says. “Everyone recognises us from our dress-code, which has value.”

Have you read?

That dress-code is a colour: taffy pink, like sugar-coated painkillers. With their pink sarees, health department ID cards and face-masks for protection, Rathna and her colleagues took on an extensive roster of new tasks. They quarantined and tested returning migrants, knocked on doors to compile lists of people reporting coughs and fevers, explained precautionary measures: hand sanitiser, masks, physical distancing, new concepts for many in the early phase of the pandemic. The meaning of community healthcare seemed to stretch. Rathna remembers soothing the rising panic of symptomatic residents – “We told people nothing will happen. Drink hot water. Stay home for 14 days” – and coordinating rations for hungry locals and stranded outsiders who lacked the usually prerequisite Below Poverty Line (BPL) cards.

“Before COVID, our work majorly focused on pregnant women and children. Now, after COVID, we are caring for everyone – the entire village, the entire taluk, the entire district,” she reflects, referring to progressively larger Indian administrative tiers.

Spring turned to summer; the volume of coronavirus patients grew, and Rathna’s hours became erratic. She recalls “an entire night without sleep” trying to find an oxygen bed and an ambulance for an elderly man from her village, whose severe hacking cough left him no opportunity to catch breath. She was afraid for him; she says – “but by god’s grace he is doing very well. Today, he and his neighbours say to me: if you had not shifted him to the hospital, then it would be a very difficult situation. I feel very happy when I hear them.”

The scale of the ASHA operation – a million women, each responsible for a thousand people, dotted across a vast nation of well over a billion – can seem abstract, but on the frontline, the work is about personal relationships: the intimacy of community. As Komala BK, an ASHA mentor responsible for over 1,200 ASHAs in Bengaluru Urban, explains, “An ASHA knows her area. She’s staying in that village for so many years, working for five years, ten years, doing rounds of that area. She knows about her people even more than she knows her sisters.” Rathna agrees. A decade of mutual familiarity came into play this last year: it meant people trusted her enough to report their symptoms, and submitted to swab testing even when they were sure they were well.

Not all ASHAs have felt as safe and supported as Rathna this past year. Though COVID-19 added hours to the average ASHA’s shift, that change was often insufficiently reflected in persistently small, and often delayed, paychecks. At least eighteen ASHAs died of COVID in 2020, including one woman from Bengaluru Urban, and some women have found themselves pressured by family to abandon their newly risky duties. In many places, ASHAs were provided insufficient personal protective gear (PPE), and some reported attacks by citizens and police. In August, 600,000 ASHAs countrywide staged a two-day strike calling for, among other things, better pay, better PPE, and a shift in their job’s status (they are currently classed as “volunteers”) that would entitle them to minimum wage.

Rathna was not among them. The pandemic workload has been “tough”, she admits, but says, “we executed it happily.” Recognition has come in a variety of forms – the thanks of the grateful family members of patients, a “Corona Warrior” award from the panchayat, or village council, and, most recently, a shot in the arm. On 18 January, a precious first cargo of coronavirus vaccine vials arrived at Anekal primary healthcare centre for frontline workers, and 11 days later, Rathna received her first jab. “We were very happy – they identified us and vaccinated us first,” she says.

And when the mass roll-out starts, she’ll be out there, knocking on doors again. “We will take people to hospital, get them vaccinated,” she says, “and bring them home.”