Drug-resistant superbugs set to kill 39 million people by 2050, Lancet study warns

Antimicrobial resistance is set to be one of the biggest global health threats; vaccines are one of our best tools to prevent catastrophe.

- 18 September 2024

- 4 min read

- by Priya Joi

A study in The Lancet this week shows that more than one million people died from antimicrobial resistance (AMR) globally each year between 1990 and 2021. And it has a dire prediction: deaths are set to increase by 70% by 2050 compared to 2022. Thirty-nine million deaths are predicted to be directly attributable to AMR, while a staggering 169 million deaths will be associated with AMR.

There is one silver lining, however: over the last 30 years, AMR deaths among children have declined by half due to increased access to vaccines.

“These findings highlight that AMR has been a significant global health threat for decades and that this threat is growing,” said study author Dr Mohsen Naghavi, Team Leader of the AMR Research Team at the Institute of Health Metrics (IHME), University of Washington, USA.

The study is the first in-depth analysis of global health impacts of antimicrobial resistance, undertaken by a large team of researchers as part of the Global Research on Antimicrobial Resistance Project. It is also the first to analyse AMR trends around the world.

“One key reason fewer children are dying of AMR is the success of vaccination campaigns, especially the polyvalent vaccine against streptococcal pneumonia.”

- Dr Gisela Robles Aguilar, a study author and senior researcher on the Global Burden of Disease at the University of Oxford, Nuffield Department of Medicine

Data from 1990 to 2021 shows increasing resistance to critically important antimicrobials, with all but one of seven key pathogens that the WHO has deemed as hardest to treat leading to more deaths in 2022 compared to 1990.

The study looked at 520 million datasets, including hospital discharge records, insurance claims and death certificates from 204 countries. Between 1990 and 2021, AMR deaths among children under five years old declined by 50%, while those among people aged 70 years and older increased by more than 80%.

“One key reason fewer children are dying of AMR is the success of vaccination campaigns, especially the polyvalent vaccine against streptococcal pneumonia,” Dr Gisela Robles Aguilar, a study author and senior researcher on the Global Burden of Disease at the University of Oxford, Nuffield Department of Medicine, told VaccinesWork.

In future, the researchers predict that deaths will be highest in South Asia. This is a shift from the current situation, where sub-Saharan Africa has by far the highest number of deaths from AMR.

The shift will happen, explained Dr Robles Aguilar, because AMR deaths among children under five are projected to halve by 2050 globally, as deaths among people 70 years and older more than double. “The sub-Saharan population will remain comparatively young compared with Asia”, she said, “and Asia’s ageing population is set to be at far greater risk of AMR.”

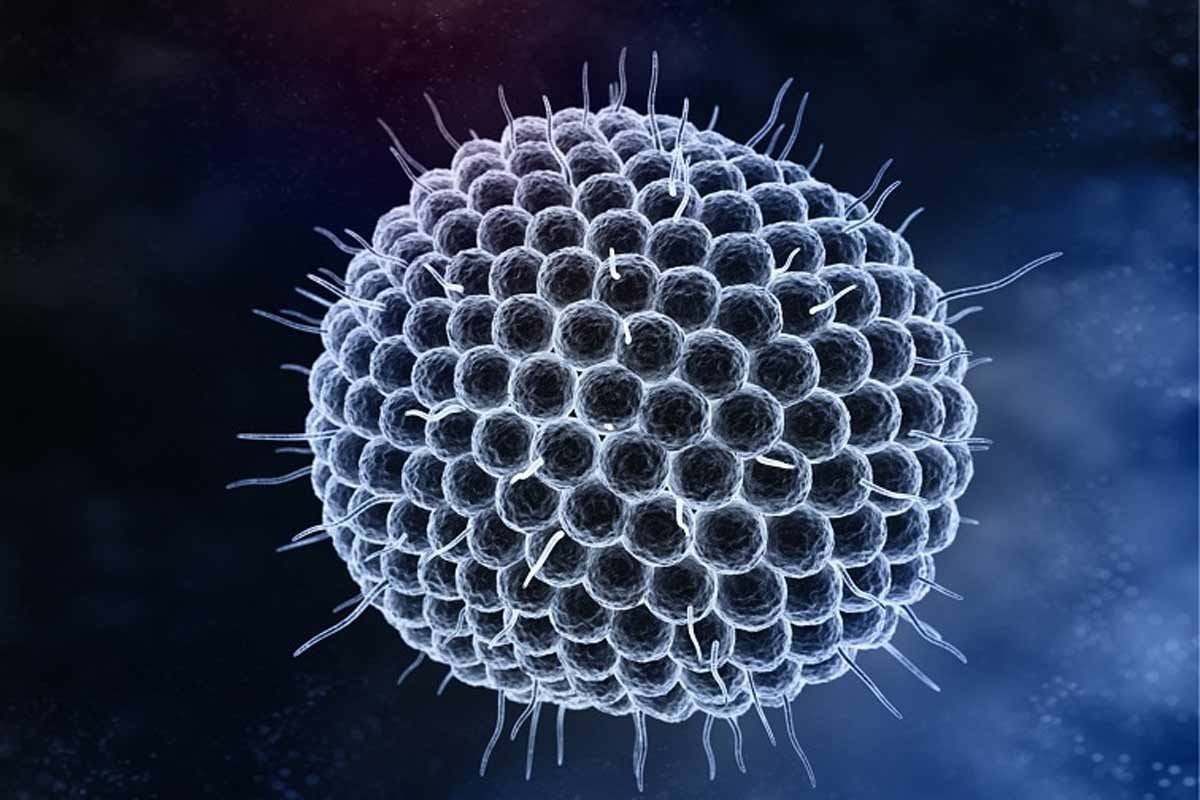

The ability of deadly pathogens to withstand treatments designed to kill them has long been a challenge, but progress to fight the rise of resistance has been difficult because of its complex drivers.

The overuse or misuse of antibiotics (including not completing a course of treatment) is one driver of AMR, but antimicrobials are also used indiscriminately to prevent and treat infections in food animals, and waste run-off from drug manufacturing can pollute the environment.

This will mean those in human, animal and planetary health working together in close collaboration, say the researchers. Vaccines remain a cornerstone of the battle against AMR, they say: “First, by preventing infection, there is no opportunity for resistance to affect health loss. Second, the prevention of even antibiotic-susceptible infections leads to a reduction in the number of people receiving antibiotics, which reduces the selection pressure for drug-resistant bacteria.”

Pathogens such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae have candidate vaccines in in the late stages of clinical trials, so it is feasible we might see a vaccine for these, said Dr Robles Aguilar. But, she added, “there are other deadly bacteria, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, or MRSA, for which there is no advanced vaccine candidate just yet, and as older people are at high risk of contracting this in hospital, a vaccine is urgently needed.”