Meet the Zimbabwean health worker helping mothers in a religious sect to protect their kids

The Johane Marange apostolic religious sect preaches against medical intervention, but some adherents have decided leaving children unimmunised is not worth the risk. Sibongile Mukwananzi is on hand to help them.

- 29 January 2025

- 6 min read

- by Farai Shawn Matiashe

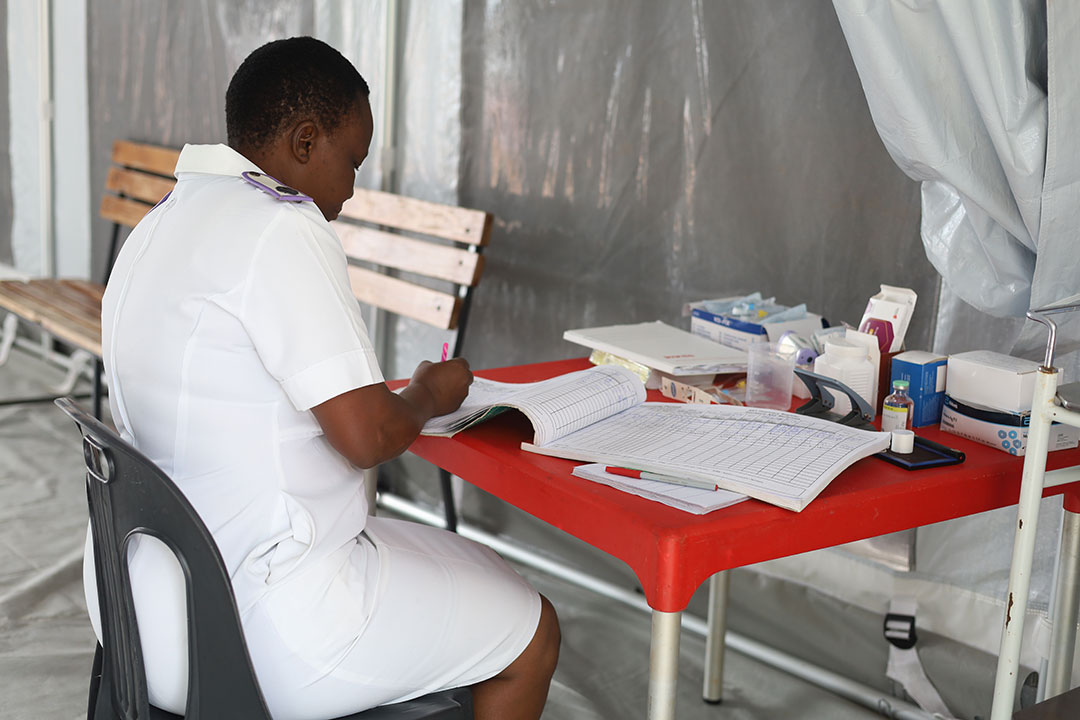

When Sibongile Mukwananzi signed up to work as a village health worker in 2020 in Marange, a rural part of eastern Zimbabwe, she thought her new job sounded fairly straightforward.

Credit: Farai Shawn Matiashe

But she hadn’t reckoned with the Apostles of Johane Marange – a religious sect, known for their opposition to seeking any kind of medical care.

Mukwananzi was born and bred in Mutare, a city some 92 kilometres away from her new base. Her neighbours attended different churches, most of them from a variety of protestant denominations, and most of them with fairly mainstream approaches to healthcare.

Credit: Farai Shawn Matiashe

But the apostolic adherents of Marange consider that divine intervention – via prayer and devotion – is the only pathway to healing. For many sect members, even basic childhood immunisation seems tantamount to a rejection of faith.

“I have been violently chased away from some homes after I had gone to mobilise babies to be vaccinated,” Mukwananzi tells VaccinesWork one rainy and windy morning in January.

“Seeking modern treatment is against their doctrines. One risks being expelled from the church if caught going to the clinic.”

But disease threatens even the most faithful, so 42-year-old Mukwananzi’s challenge is to convince these people to bring their babies to the clinic for routine immunisations against deadly childhood diseases like polio and measles.

Credit: Farai Shawn Matiashe

Mukwananzi, who moved to Nyamadzawo village in Marange – her catchment area – after getting married, also mobilises people from this community to get vaccinated for diseases like cholera, which surged in many parts of Zimbabwe, including this one, in 2023 and 2024.

A back door to health

Motivated by her desire to live in a clean and safe environment, Mukwananzi works together with community leaders, health workers and non-governmental organisations (NGOs) to educate the community about vaccine-preventable diseases.

As a village health worker, she gains her knowledge and skills by attending workshops and interacting with health professionals.

A typical day involves waking up early to do her house chores, picking up her bags – stocked with medicine and pamphlets – then riding a bicycle into the villages, going door to door, and educating and raising awareness about routine immunisation.

After identifying babies who have missed out on the vaccines they need, she refers them to Zvipiripiri Clinic, the nearest health facility.

Together with nurses at Zvipiripiri Clinic and workers from certain supportive NGOs, Mukwananzi has devised a plan for people from the Johane Marange sect to seek treatment under the radar of church leaders.

Credit: Farai Shawn Matiashe

“They are given special treatment at the clinic to evade church leaders,” she says. The apostolic adherents are given a pass to avoid long winding queues of other patients waiting to be attended to, to make sure they get in and out quickly.

“We also have a timetable when they come in the afternoon, when everyone would have been treated and dismissed.”

An official from the Health Ministry in Mutare says some mothers bring their babies for vaccination in the evening to avoid being seen by fellow church members.

“It is a serious offence to be seen seeking treatment. This plan is working. They are cooperating. There has been a rise in vaccine uptake in this community,” says the official, who declined to identify themselves publicly.

“This plan is working. They are cooperating. There has been a rise in vaccine uptake in this community.”

- Health official, Mutare

Mukwananzi said she often explains to parents that only vaccines and other treatments can prevent deaths during outbreaks of diseases like cholera and measles.

“After seeing that they are losing their loved ones from something that can be treated, they comply,” she says.

Pilgrims at risk

Nearly 200,000 pilgrims from around the country and beyond the national borders gather at Mafararikwa Shrine in Marange for annual conferences. Such a gathering creates the perfect conditions for a cholera outbreak.

Marange was one of the epicentres of the cholera epidemic that Zimbabwe battled from February 2023 to August 2024. The vaccine-preventable disease infected more than 20,000 people and claimed the lives of more than 400, according to UNICEF.

“After seeing that they are losing their loved ones from something that can be treated, they comply”

- Sibongile Mukwananzi, village health worker

Mukwananzi found herself on the frontline of a crisis, mobilising families from the Apostles of Johane Marange to seek treatment at a local clinic.

“Some families lost 20 to 30 members in a short time. And they did not want any help from me,” she says, explaining that families can be very large – many people in the community are polygamous, and one man might have as many as 16 wives and 100 children.

When oral cholera vaccines (OCVs) rolled out, targeting 1.3 million people in the outbreak epicentres in January 2024, Mukwananzi was able to mobilise some church members from her community to take it. Not only was each vaccinated person individually made safe from the effects of the diarrhoeal disease, but they also acted as blockers on the rate of transmission. OCVs stimulate an immune response in the intestine, thereby reducing the capacity of the cholera bacterium to colonise the gut in the first place, meaning that vaccinated people are unlikely to pass the pathogen along.

Measles alert

It wasn’t Mukwananzi’s first outbreak response. In 2022, an outbreak of measles infected 7,701 people, and killed 747 across Zimbabwe.

A mass vaccination campaign began in August 2022 and aimed to reach around 2.3 million children aged between six months and five years by 9 September 2022, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

A Johane Marange sect leader, who declined to be identified by name, says Mukwananzi’s efforts saved lives in the community.

“No matter how often you turn her away, she keeps coming to take mothers and their babies to the clinic for vaccination. She is so determined to save everyone in this community,” they said.

Have you read?

Dealing with allowances

Mukwananzi is one of more than 20,000 village health workers across Zimbabwe navigating a diverse range of challenges – from vaccine hesitancy, to sparsely populated villages, mountainous terrain and risks from wildlife – to get the population protected with vaccines.

Credit: Farai Shawn Matiashe

Itai Rusike, an executive director at the Community Working Group on Health (CWGH), says village health workers are the “glue” that connects Zimbabwe’s healthcare system to communities.

“They are critical to health promotion, disease prevention, early diagnosis and referral, and helping people stay on treatment and healthy,” he says.

In 2024, the government announced plans to absorb village health workers into the civil service, hopefully helping to tackle the current disparities in the payment of allowances. Village health workers are paid differently by donors.

“We commend the commitment by the government to now absorb the village health workers onto the Government Payroll System supported by the National Health Budget, as this is more sustainable rather than the overreliance on external donors. A strong village health workforce is the cornerstone of every health system,” he says.

Mukwananzi says her allowance is normally deposited into her mobile wallet every three months, which makes it difficult to look after her family. “They told us we would soon get paid like other health workers. I would be happy if that is implemented,” she says.