In Zimbabwe, progress on HIV management is also helping protect patients from other deadly threats

Ninety-five percent of Zimbabweans know their HIV status. That means that the more than a million people living with the virus can preventively manage the risk from other dangerous infections, like TB and HPV.

- 19 July 2024

- 7 min read

- by Farai Shawn Matiashe

A red sun is setting over the mountains when Estella Mufute arrives at her home in Sakubva, a densely-populated suburb of Mutare, a Zimbabwean city near the border with Mozambique. She drops her bags: it’s been a long day at the local clinic, where she offers voluntary services in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing and counselling.

The 52-year-old mother of six instructs one of her daughters to prepare dinner for the family as she settles down to take a breather. Mufute has been living with HIV for the past 23 years. In that time, the meaning of the diagnosis has changed profoundly. “Back in 2001, when I tested positive, there was no medicine in public hospitals. It was only available in pharmacies, where it was expensive,” she told VaccinesWork.

“I get screened for cervical cancer twice a year. I am also given TB preventive treatment (TPT) every three years. If I fall sick, I rush to the clinic. I do not want surprises.”

- Estella Mufute, living with HIV since 2001

She recalls antiretroviral treatment (ART) became available in public health facilities in 2004, but it was only limited to people with a low CD4 cell count, which is used as a measure for how badly the virus has damaged the immune system. People with a CD4 count below 200 are considered at great risk of developing serious illness.

It was in 2007, when her CD4 count was 94, that Mufute started taking ART, a combination of drugs taken daily to suppress viral load, and to improve immune system function in order to reduce risks of infections. She has never defaulted on a dose of the medication, she says.

95-95-95: a milestone moment

Last year, Zimbabwe reached the United Nations’ 95-95-95 target, becoming one of the first few countries to achieve it in Africa, according to the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS).

The target calls for 95% of people who are living with HIV in a selected country to know their HIV status while 95% of people living with HIV are on ART and 95% of those achieve viral load suppression.

Figures from the Ministry of Health show that of the 1.3 million people living with HIV in Zimbabwe, 1.2 million are on HIV treatment and 97% of those have achieved viral suppression.

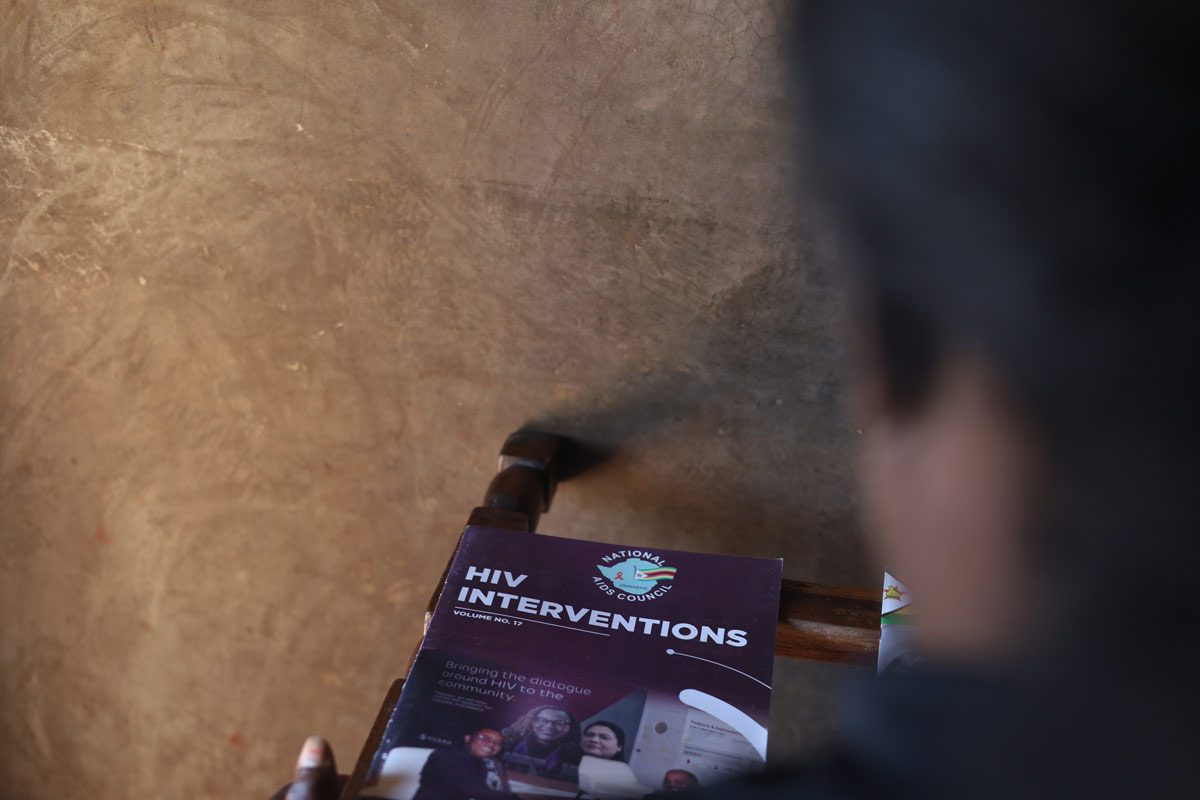

“It means that once the viral load is suppressed, these individuals can no longer transmit HIV to their partners, or even if it’s a pregnant woman, to their unborn baby,” said Dr Bernard Madzima, chief executive officer at National Aids Council (NAC), a state organisation that coordinates and facilitates the national multi-sectoral response to HIV and Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Mufute is a beneficiary of the country’s programme for the elimination of Mother to Child Transmission (MTCT) of HIV, as she successfully gave birth to a HIV-negative baby in 2013 and exclusively breastfed.

Getting there

The government introduced the so-called AIDS levy in 1999, where individuals, companies and trusts pay 3% income tax towards responses to the HIV and AIDS epidemic that exploded in Zimbabwe during the 1980s.

To complement this, international aid agencies including the Global Fund, United States Agency for International Development and the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) support interventions like HIV treatment distribution, community-based support groups, condom supplies, voluntary medical male circumcision, preventative measures like pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and HIV testing and counselling.

Owen Mugurungi, director for the AIDS and Tuberculosis (TB) programme in the Ministry of Health, said Zimbabwe has been implementing evidence-based interventions recommended by UNAIDS and the World Health Organization.

“This allowed for same-day testing and initiation of treatment for all positives. The treatment is standardised into first-line and second-line treatment and has also been decentralised to primary health level. So, more people can be managed at that level, therefore, improving access,” he said.

Mugurungi said they also provide multi-month HIV treatment drugs for up to six months for clients who are stable, which can prove key in improving adherence, which in turn improves viral load suppression.

HIV prevalence rates in Zimbabwe have declined from 25% in 2002 to around 11.58% in 2021, according to UNICEF.

AIDS-related deaths have also sharply declined to below 20,200 in 2021, from 130,000 in 2001.

Living with HIV – and without HPV

For the 1.3 million people living with HIV in the country, even for those with suppressed viral loads, other pathogens still present a risk to be managed with caution.

Mufute said she regularly gets tested for infectious diseases because she knows her immune system is vulnerable, putting her at higher risk of other diseases, such as cervical cancer and TB.

“I get screened for cervical cancer twice a year. I am also given TB preventive treatment (TPT) every three years. If I fall sick, I rush to the clinic. I do not want surprises,” she said.

Dr Vitalis Guvava, a provincial technical officer at JF Kapnek Zimbabwe, a health organisation, said some of the key risks for people living with HIV include TB, pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), other severe bacterial pneumonias, fungal infections of the skin, mouth and oesophagus, meningitis from bacterial or fungal infections, as well as sexually transmitted infections like HPV, which predisposes women to cervical cancer.

“The basic reason for this is because they have a weaker immune system. In uninfected individuals, their immune systems can fight these infections, but because the body's immune system is compromised in HIV-infected individuals, they acquire these infections much more,” said Dr Guvava.

Have you read?

Dr MacDonald Hove, a provincial programme manager at Organization for Public Health Interventions and Development (OPHID), which focuses on HIV prevention, said given that hepatitis B and HPV are sexually transmitted just like HIV, people reduce the risk when they know their status and practise safe sex.

“Hepatitis B virus causes an infection which may ultimately lead to liver disease or cancer. HPV causes cervical cancer and the risk is doubled when you have concomitant HIV infection,” he said.

Mufute’s husband died of meningitis. She suspects he was HIV-positive even though they did not know his status.

Know your status, manage your risk

Medical and Dental Private Practitioners Association of Zimbabwe president Johannes Marisa told VaccinesWork: “It is good to know your status as it makes you proactive in the event that one gets a suspicious infection. Many people who do not know their status are caught off-guard, and you hear of sudden deaths which can come from conditions like meningitis, TB and pneumocystis,” he told VaccinesWork.

Tracy, from Hobhouse, a populous suburb in Mutare, who asked to be identified only by her first name, says she avoids gatherings and wears face masks to protect herself from infectious diseases.

“This helps a lot. I know my immune system is weak. I get screened for TB and cervical cancer twice a year,” said the 54-year-old mother of four, who has been HIV-positive for the past 12 years.

Tracy, who speaks slowly, said she manages her health by staying faithful to one partner, eating healthy food and taking her ART on time.

Screening and prevention

Guvava said early screening and the use of preventive therapies help in managing other infectious diseases among people living with HIV.

“For example, with cervical cancer, one can get screened through either HPV DNA screening where the presence of the virus is checked for or through Visual Inspection with Acetic acid (VIA) with treatment offered for those with suggestive findings,” he said.

“For TB, people get screened and those with no symptoms or signs suggestive of TB are put on TPT. In individuals with very low CD4 counts and cryptococcal infection, fluconazole preemptive therapy can be given until their immune system has recovered enough.”

Guvava said they give cotrimoxazole prophylaxis to prevent common infections like PCP, diarrheal, or other bacterial infections.

Mufute continues with her counselling to people living with HIV, offering them tips on staying healthy.

“Eating a balanced diet is key and so is taking treatment on time, getting screened for infectious diseases often and practising safe sex,” she said.