The World’s First Vaccination Campaign

At the turn of the 19th century, news of a 1796 medical breakthrough called 'vaccination' started to spread around the world. A fascinating recent book, War Against Smallpox by Michael Bennett, traces the subsequent dissemination of the actual vaccine – an extraordinary global mission, which achieved stunning successes. By the winter of 1805, a vaccination campaign was underway among the nomadic peoples of remote eastern Siberia.

- 12 April 2021

- 6 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

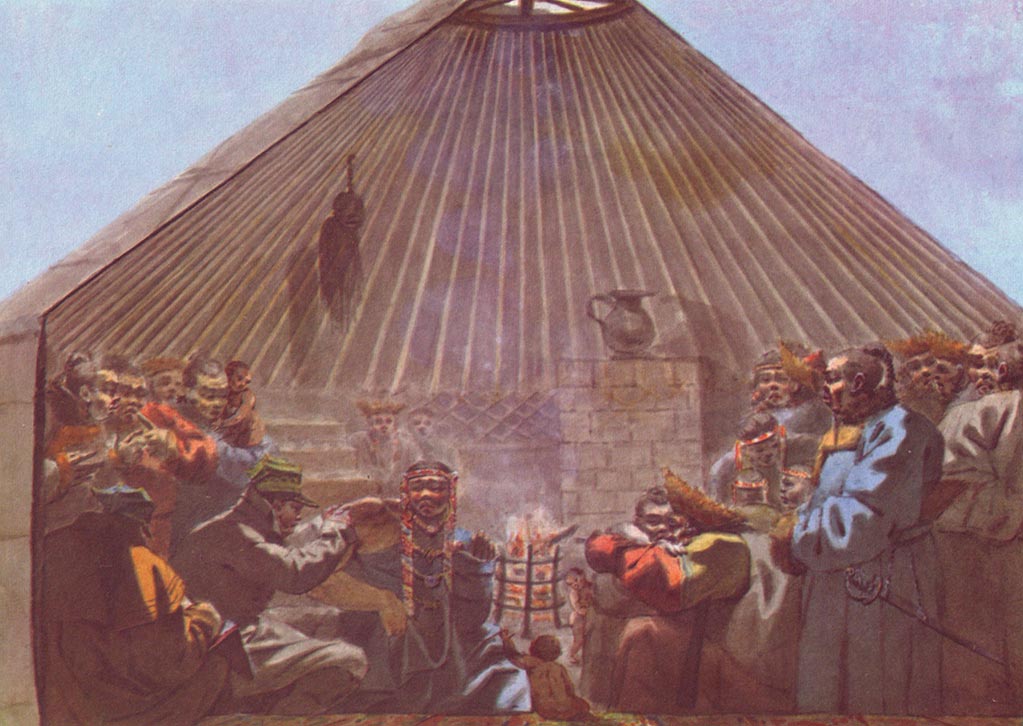

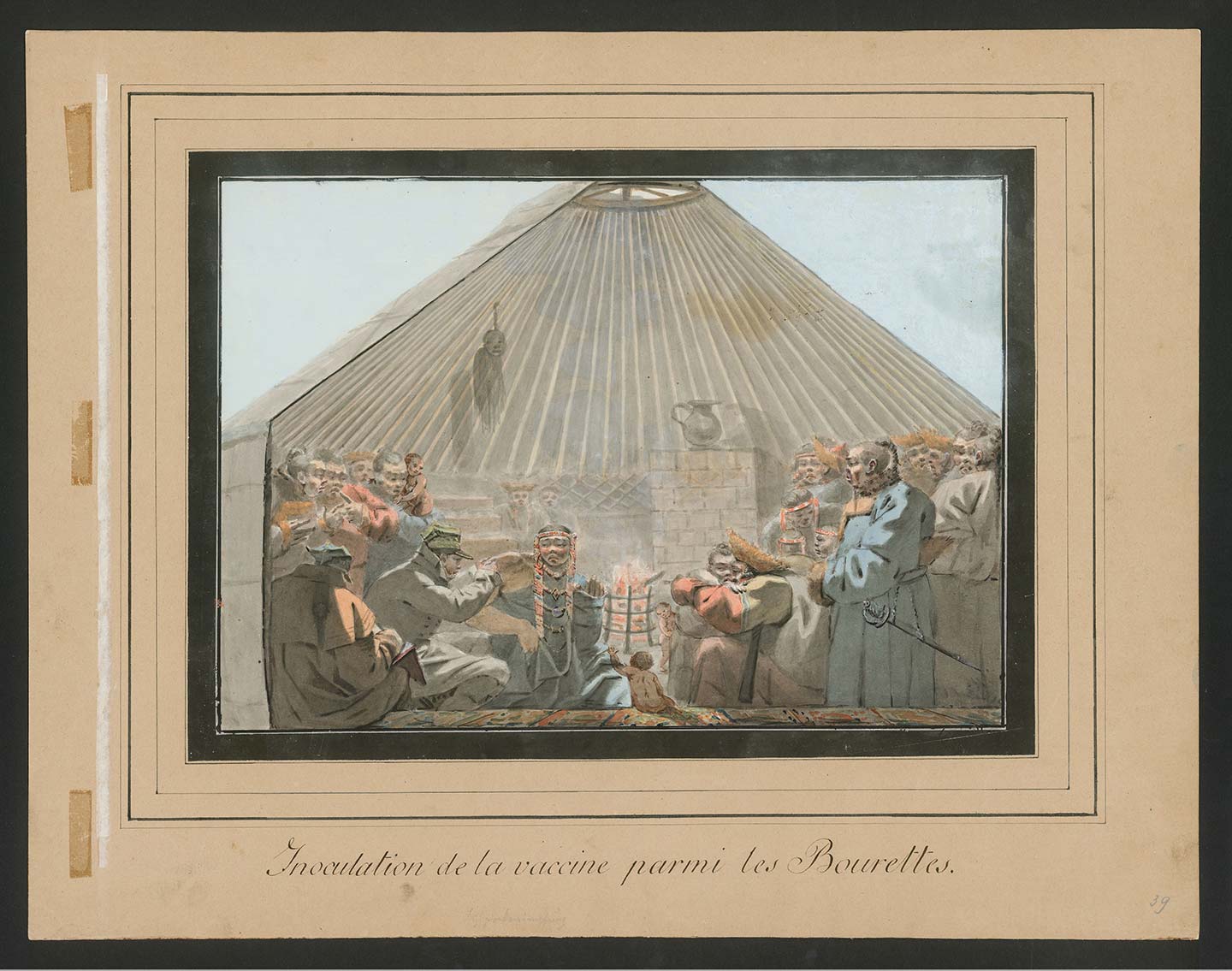

It’s winter in eastern Siberia in 1805, somewhere on the wide skirt of Lake Baikal, not far from the Chinese border. Inside a Buryat yurt, a huddle of nomadic herders in thick coats with furred cuffs are holding their arms folded across their chests. Closer to the fire, which puffs smoke towards a central aperture in the conical roof, one woman has tugged down her sleeve. Her upper arm is exposed. An outsider, a man in the livery of the Tsar’s army, crouches beside her, all concentration.

Kids fostered or apprenticed out to rural families carried vaccines with them in their arms, helping spread smallpox protection into the countryside.

The soldier’s name is Petrov. Though he speaks the Buryat language, he has arrived on these spare plains with a diplomatic delegation from St Petersburg. But his own concern is not military nor diplomatic, but medical: he is an army surgeon, and he is inoculating the woman with a dose of lymph fluid infected with the cowpox virus.

Elsewhere in the yurt, another outsider hunches over his sketchpad. This is Dr Joseph Rehmann, a German physician, scientific enthusiast, and able watercolourist, who has decided that this is an occasion worth recording. He is keenly aware that the gathering in the yurt is part of something historic and transformative: the world’s first vaccination campaign.

Here, in the nomad camp, the arrival of the vaccinators has prompted a celebratory mood. After all, the vaccine promises safety from the feared and anticipated next wave of smallpox, which, in thinly-populated regions like this, can bring total devastation.

Buryats ride up on tough little horses from miles around to take part. Petrov and Rehmann are offered milk, spirits, special tea; they are led on tours of holy sites. Within approximately a month of mini-expeditions from a main base at Troizkasafsk, Rehmann will record 744 Buryats1 as newly vaccinated.

Credit: Stuttgart, Wuerttembergische Landesbibliothek, Cod. Don. C I 12, A, Blatt 39r

“The first thing that really struck me was just how strong – in many ways – global networks were. Particularly if you look at the medical community,” Professor Michael Bennett told VaccinesWork one recent morning over Zoom. His 2020 book, War Against Smallpox: Edward Jenner and the Global Spread of Vaccination, makes a study of those networks –ad-hoc and diverse, fuelled by “the great enthusiasm” of early proponents.

When Petrov and Rehmann were touring Buryat camps in Siberia 1805-6, only ten years had passed since Edward Jenner had conclusively demonstrated the efficacy of cowpox vaccination against the smallpox, “the most dreadful scourge of the human species,” 5000 miles away in Gloucestershire.

Have you read?

In Russia, where vaccination’s riskier forerunner, variolation, had been taken up with proselytizing energy by the ruling class, vaccination had been eagerly awaited since early 1800. By then, news of Jenner’s 1796 success had filtered along diplomatic routes connecting London and St Petersburg. But in the second half of 1800, Bennett says, relations between Britain and Russia had fractured, and the arrival of the vaccine was delayed. Efforts by Tsarina Maria Fedorovna to procure dried vaccine stumbled when the material turned out to be inert.

Finally, in October, before an assembled audience of eminent medical men and other notables, a Moscow foundling called Anton Petrov became the first Russian to be vaccinated – and was renamed Anton Vaktsinov. Fluid from the resultant pustule in Anton’s arm was drawn and used to vaccinate the next child - this was the only way to vaccinate people in an age before lab-produced vaccines. By late 1801, the Foundling House, or rather, the foundlings within it, was established as the site of Moscow’s vaccine stockpile.

Kids fostered or apprenticed out to rural families carried vaccine with them in their arms, helping spread smallpox protection into the countryside. The Dowager Empress herself arranged for a recently-vaccinated Moscow girl to travel to St Petersburg, to inaugurate an arm-to-arm chain of immunisation in the Imperial capital.

Getting the vaccine out into the regions – including Siberia – was a more ambitious matter. In 1802, Tsar Alexander authorised an expensive plan designed by a Dr Franz Buttats to bring cowpox – arm-to-arm, a human relay race – to the provinces. In May 1805, viable vaccine made it to Irkutsk, on the other side of the Urals.

That year, a diplomatic delegation to China was convened under the leadership of Count Golovkin. Three months before the embassy departed, Dr Rehmann, who lived in St Petersburg, applied to tag a vaccine expedition onto Golovkin’s mission. The convoy travelled south, then east, and reached Irkutsk in September.

In December, a diplomatic break-down halted the Golovkin party at the Chinese border. Rehmann, who aimed to bring vaccination to China, and had prepared an address to the Chinese nation about the history of cowpox inoculation, was left in Troizkasafsk. If he was frustrated, he wasn’t idle: “he was delighted by the Buryats and found them disposed to accept vaccination,” Bennett writes.

Other Russian physicians in the region were enthusiastic proponents of Jenner’s method, Rehmann found, but not all patients were as receptive as the Buryat. In his 1806 report to the Minister of the Interior, Rehmann called for more resources and more pressure. He urged: “this salutary pustule … is even more precious in sparsely populated lands, where the life of each individual is more closely linked to the good of the state.”

For interested readers, the Württembergische Landesbibliothek in Stuttgart, Germany has digitised the entire album of Dr. Rehmann's watercolours, entitled "Voyage de St Petersbourg a Ourga dans la Mongolie Chinoise par la Russie orientale et la Siberie." Our thanks to the Manuscripts Department for their permission to publish Rehmann's picture of the vaccination among the Buryats.