What is Nipah virus, and why is it spreading again?

The virus causes a deadly brain-swelling fever, and it has just emerged again in India. Here’s what you need to know.

- 31 July 2024

- 4 min read

- by Priya Joi

India is battling Nipah virus again in its southern state of Kerala after the death of a 14-year-old boy.

Contacts of the boy have so far tested negative, but state health authorities are aware of the urgency to rapidly contain Nipah and will be testing 460 people, including health workers.

Health authorities take Nipah so seriously because the disease has no vaccine nor cure, and it can kill nearly everyone it infects. In Kerala’s first Nipah outbreak in 2018, it killed 17 out of 18 people infected – a fatality rate of 94.4%.

In 2022 , the World Health Organization (WHO) put Nipah virus on its list of priority pathogens for the first time, and scientists are concerned about the virus’s potential to cause the next pandemic.

The good news is that, unlike other disease-causing species such as mosquitoes that actively try to feed on human beings, bats don’t seek us out. Controlling environmental destruction so that we aren’t increasing the risk of spillover is crucial.

Outbreaks are potentially becoming more lethal

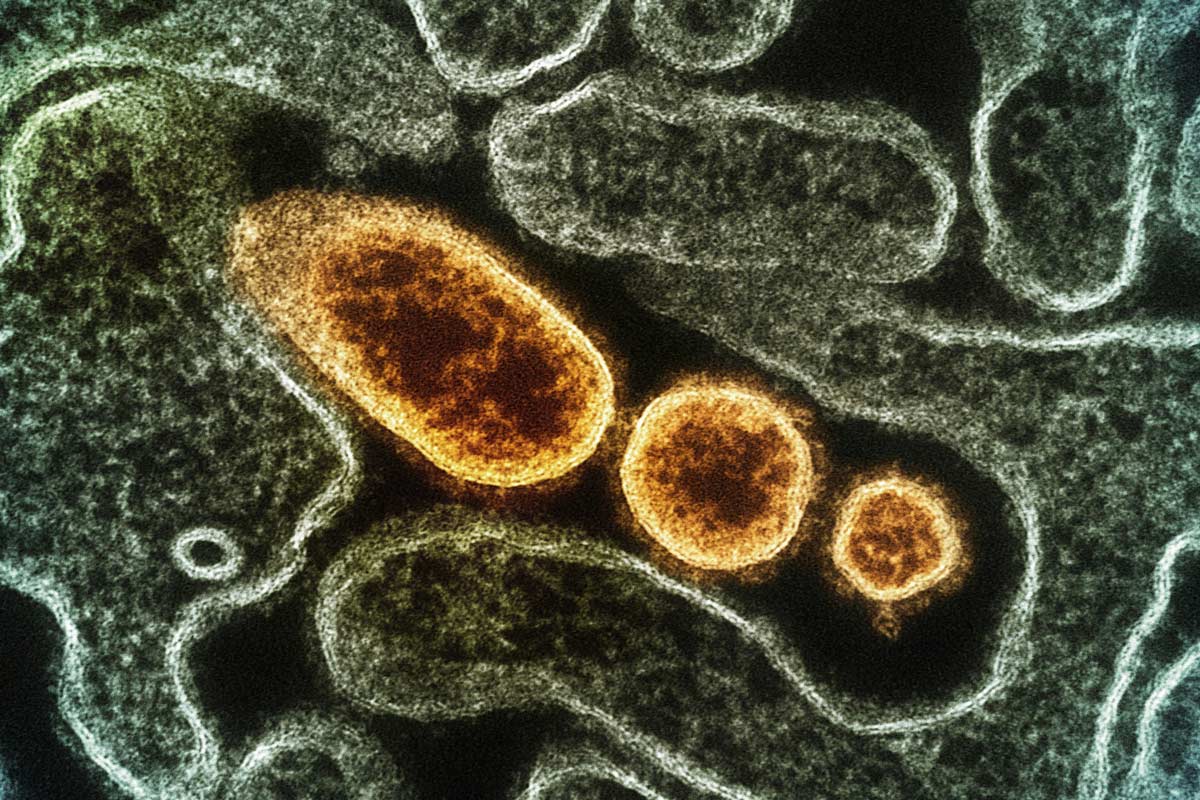

Nipah virus was only identified 25 years ago in Malaysia but has since caused outbreaks in the Philippines, Singapore, Bangladesh and India. It can cause a lethal brain-swelling fever, as well as muscle weakness, cough and breathing difficulties, and heart muscle dysfunction (the teenage boy who died in Kerala this month died of a heart attack).

Mostly spread by fruit bats, there are two strains of Nipah – the Malaysia strain (which also caused the Philippines outbreak) and the Bangladesh strain (which also caused the India outbreaks). The Bangladesh strain seems to be more severe than the Malaysia one.

Though numbers of cases are still too few to draw firm conclusions, the virus could be causing more severe symptoms. Mortality during the first Bangladesh outbreak in 2001 was 69%; during the 2013 outbreak it was 83%; and the 2018 outbreak in Kerala had a fatality rate of 94.4%.

Deforestation and habitat loss may be causing more outbreaks

Since the 1999 Malaysia outbreak, there have been outbreaks every year in Bangladesh, with a 2023 outbreak causing the most fatalities.

Rapid industrialisation and the destruction of forests has meant that not only are bats losing their natural habitats, they are being pushed much closer to human residential areas. This means that there are increasingly more 'jump zones': areas where the viruses that bats harbour can jump to humans.

This is bad news because bats are super-incubators that can spread deadly viruses including Nipah, coronaviruses, Ebola and Marburg.

The virus can spread between people

Animals and humans tend to catch the infection from fruit bats by eating fruit or vegetables contaminated with bat urine or saliva. In Bangladesh, some outbreaks have been caused by drinking contaminated date palm wine, made by fermenting date palm sap. Date palm trees are tapped by collecting the sap overnight, during which time fruit bats might lick or urinate into the sap collecting device.

However, human-to-human transmission has been increasingly noted, with the virus spreading between people through contact with body fluids and through respiratory droplets produced when people cough or sneeze.

A 14-year study of Nipah transmission published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2019 noted that while Nipah outbreaks have been small so far, “larger, self-sustaining epidemics may occur if the virus becomes more transmissible”.

Have you read?

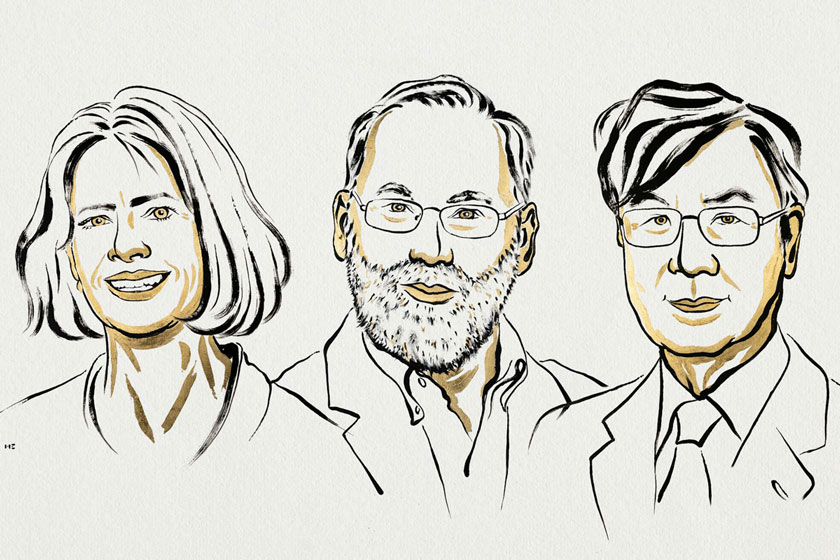

Scientists trying to develop a Nipah vaccine

There are still no approved human vaccines or treatments for Nipah, but several are in clinical trials, including the ChAdOx1 NipahB vaccine, which entered its first human trialearlier this year.

Developed by Oxford University’s Pandemic Sciences Institute, the vaccine uses the same viral vector vaccine platform used to make the Oxford/AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.

The next pandemic?

Ultimately, the major concern with Nipah is its potential pandemic threat. The virus is so deadly that many governments classify it as a bioterrorism threat, and few laboratories are allowed to study it. So far, this lethal virus has not been able to spread too far given that it still isn’t easily transmitted between people.

However, like SARS-CoV-2 that causes COVID-19, Nipah is an RNA virus. These viruses tend to mutate often, making them more adaptable so that they can infect different species, develop new methods of transmission or evade vaccines.

The more times a virus can jump to other species, especially into people, the more chance it has to evolve into one that can spread easily from human to human. In India, nearly half a billion people live in these ‘jump zones’ between bats and humans.

The good news is that, unlike other disease-causing species such as mosquitoes that actively try to feed on human beings, bats don’t seek us out. Controlling environmental destruction so that we aren’t increasing the risk of spillover is crucial.