In rural north India, school teachers prescribe a tweaked curriculum against further pandemic disruption

Where online learning is not an option, school doors have to remain open. The best way to make sure they do? Lessons on health, hygiene and vaccination.

- 15 November 2022

- 4 min read

- by Aayushi Shukla

It's 11:30 in a small village in the Siddharthnagar district of Uttar Pradesh: time for the mid-day meal at P.S. Mahulani, the local government-run primary school. Jitendra Kumar, a seven-year-old boy, is using a bar of soap to wash his hands before eating. The rest of the kids line up behind him for their turn at the wash-basin.

"My teacher explained the value of hand washing. It can help me protect myself and my family from diseases like COVID-19," says Jitendra.

“When these kids are taught the value of hygiene, vaccines and overall health, they not only take this information home, but also grow up to be responsible adults who will take care of their community based on the right knowledge."

"When schools in India [re]opened at the start of 2022, many parents were apprehensive about sending their kids," says Madhu Mishra, a teacher at P.S. Mahulani. Parents, she says, are "emotional" when it comes to the well-being of their children – faculty needed to find a way to win their confidence.

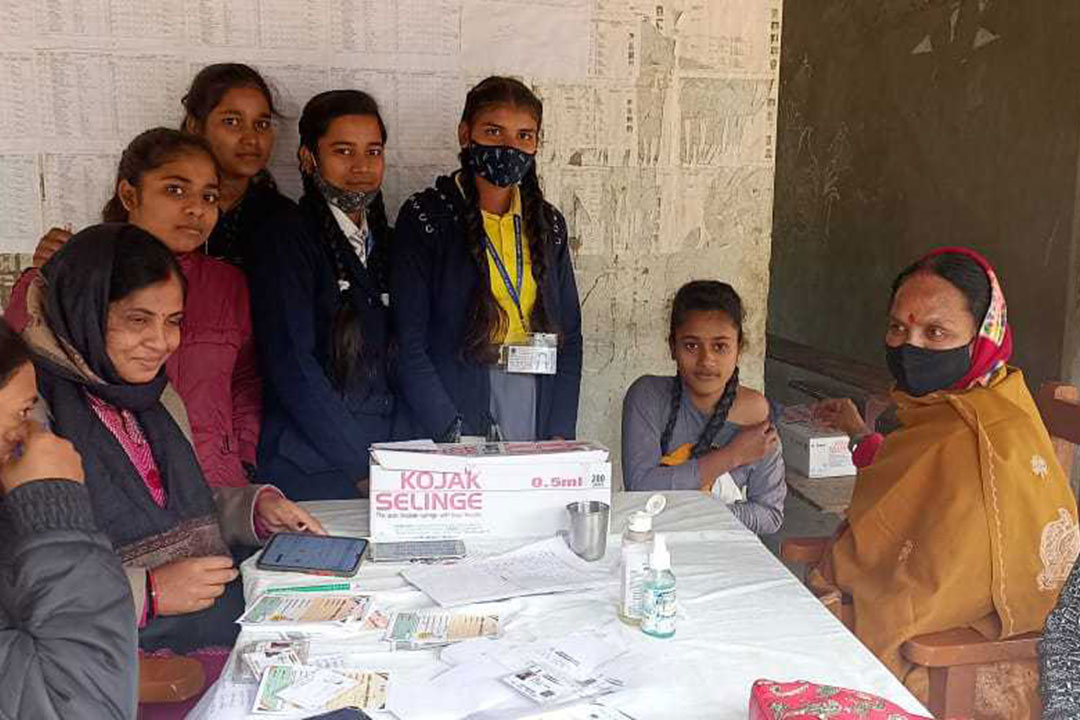

Credit: Aayushi Shukla

"Even though there were no active cases in the village, we established proper procedures to safeguard kids in school. Starting from maintaining social distancing to following sanitation guidelines, we made sure that children have a safe place to get an education," Mishra explains. "We have also started teaching kids about hygiene and health in general. This has helped convince parents to send their kids back to school."

Fuller classrooms, healthier communities

The last two years have been tough on education in rural India. While private schools in cities have been able, in many cases, to give digital lessons to children, most village-dwelling kids have not had access to a smartphone or laptop. Rural school attendance dropped sharply amid pandemic disruption; the already-considerable education disparity between urban and rural kids widened further.

To teachers in Siddharthnagar, where adult literacy rates stood at just under 60% at last census, it was clear: the only way to get their students back on track was to get them back in classrooms.

Have you read?

Moreover, getting school-aged kids learning again could pay major public health dividends in the longer term – for instance, by encouraging better vaccination uptake in a district whose routine childhood immunisation rates lag the national average by a good ten percentage points, according to the 2019-2021 National Family Health Survey.

According to Dr Anita Mehta, a paediatric physician at BRD Hospital in Gorakhpur, a major referral centre about 80 kilometers from Siddharthnagar, literacy and vaccination rates have a connection: "The illiteracy in the villages makes it easy for people to believe fake stories [about vaccination] that usually circulate," she says.

"Awareness is the first step towards any social change," agrees P.S. Mahulani maths teacher Anita Rai. "We are teaching children about the history of vaccines, so they understand their good effects. Building upon the history, we then make them understand the value of vaccines and how they can be lifesaving."

Dr Mehta says lessons like these can root and spread in communities: "When these kids from underprivileged sections are taught the value of hygiene, vaccines and overall health, they not only take this information home but also grow up to be responsible adults who will take care of their community based on the right knowledge. In addition, these learnings on sanitation and hygiene will also safeguard them against communicable diseases."

Bringing lessons home

Early signs are promising. "My daughter told me to get the [COVID-19] vaccine. I was unsure because of all the misinformation that was circulating around. But since she is adamant that the vaccine is good for us, we ended up getting it after her continued request. We are glad we listened to her," says a proud father, whose daughter, Sanjana, is in class 3 at P.S. Mahulani.

Madhu Mishra explains, "Education has the power to uproot all forms of misinformation. When we see vaccine hesitancy among people, we feel it is our duty as teachers to share the correct knowledge. Kids can be moulded well when they are small. Imparting education about health and hygiene can be life-changing for these kids in the long run."

Credit: Aayushi Shukla

Rai hopes that getting her students back in classrooms, and making sure they receive a "quality education", will mean these children – most of them the kids of small farmers and farm-workers – have a shot at becoming "doctors or writers".

Whether they do will surely depend on many things – not least on the kids themselves. "I want to be a police officer when I grow up," says a happy Jitendra, before running off with the other children as the bell rings.