The other disease burden: when physical sickness sows mental health trouble

Illness can take a toll on patients’ mental health, anywhere. But after a survey of psychological wellbeing post-COVID-19 found that Indians disproportionately reported being in distress, Aayushi Shukla sought insights from across the subcontinent.

- 25 July 2024

- 5 min read

- by Aayushi Shukla

Deepti Chavan of Mumbai was diagnosed with tuberculosis at the tender age of nine. "I was too small to understand it, and I got better within seven to eight months. But this wasn't the end of it," she said.

The symptoms returned. At 16, Chavan was diagnosed with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB). "I was about to take my board exams when it happened. Over six years, I had to endure about 400 injections and two surgeries, one of which involved the removal of an affected lung," she recounted. "I am a very strong-willed person, but I had to take 15 to 20 tablets every day. My vision was affected, and I had nausea and joint pain all the time. The side effects of the medicines made me very irritable. Any person wouldn't be in good shape mentally after what I went through," she recalled.

Credit: Deepti Chavan

"To improve overall care, we must strengthen our health care infrastructure to integrate mental and physical health services."

– Shreya Subbannavar Mukta, a psychologist from Pune

A shadow illness

Chavan’s experience is individual, but not unique. A recent survey on mental health in a post-COVID-19 world, conducted by Sapien Labs, found that 30.4% of Indians are distressed and struggling with their mental health, compared to 27.1% globally. This statistic quantifies a growing mental health crisis in India, which is particularly acute among those battling physical illnesses.

Mamta Kumari, who works as a house help in Delhi, recalls contracting COVID-19 in September 2021. "It was hard, because I couldn't work and support my family financially. Even after I recovered, finding work was difficult, as people were afraid to let me into their homes," she said.

Have you read?

This prolonged period of unemployment and social isolation led to depression. "I was sad but I did not know that’s an illness," Kumari remarked. "I couldn't sleep or eat properly. I kept visiting the hospital because I thought the virus was causing these symptoms. Later, the doctor told me I was depressed. I did not know what to do.”

Doctors and therapists weigh in

Dr Vijay Raghuvanshi, a neuropsychiatrist from Indore, in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh, provides a deeper understanding of the mental health impacts of physical diseases. "Mental health issues are significant on their own, but when they are caused due to a physical disease, the burden increases. Patients may experience anxiety, depression and stress due to fear of the illness, social isolation during treatment, and stigma. The economic burden of treatment and loss of income can further exacerbate these mental health issues,” he explained. Dr Raghuvanshi also pointed out that India is still developing, and has a long way to go in terms of educating people about mental health.

Shreya Subbannavar Mukta, a psychologist from Pune, shed light on the worsening incidence of mental health conditions among individuals suffering from physical diseases, particularly in villages. "In rural areas, a person's sense of worth is often tied to their productivity. When a physical disease hinders their ability to provide for their family, it can lead to significant distress. I’ve worked with TB patients in the Begusarai area of Bihar. What I found was a general feeling of hopelessness and a lot of it was due to their deteriorating physical condition.”

A major challenge is the stigma attached to mental health, which prevents many from seeking help. On this, she said, "You also need to understand that rural areas of India still struggle with basic health care amenities, like not being able to call an ambulance on time. So mental health issues often take a back seat.”

However, she noted that the rise of telemedicine since COVID-19 offers a promising opportunity to enhance access to mental health services. Mukta also emphasised the need for training primary health care workers to identify and address mental health issues in patients with physical ailments. "To improve overall care, we must strengthen our health care infrastructure to integrate mental and physical health services," she concluded.

Government support

The Indian government has long recognised the importance of mental health. Since the National Mental Health Programme (NMHP) was introduced in 1982, there has been a push to include mental health services in primary care. A major part of this effort is the District Mental Health Programme (DMHP), which operates in over 700 districts and emphasises grassroots support. This programme focuses on detecting, managing and treating mental illnesses, and includes initiatives such as work-stress management and suicide prevention.

When asked about the adequacy of the government's response to mental health care in India, Dhriti Agarwal, the founder of the Muktaa mental health helpline, which operates out of Pune in western India, remarked, "The Tele Mental Health Assistance and Networking Across States (Tele-MANAS) initiative, launched in October 2022, has made significant strides in reaching individuals in need of mental health services nationwide. But more needs to be done, particularly by focusing on marginalised communities that remain underserved and are not yet fully connected digitally. NGOs like ours, that work directly with these communities, must be included in these efforts to make sure everyone gets the support they need."

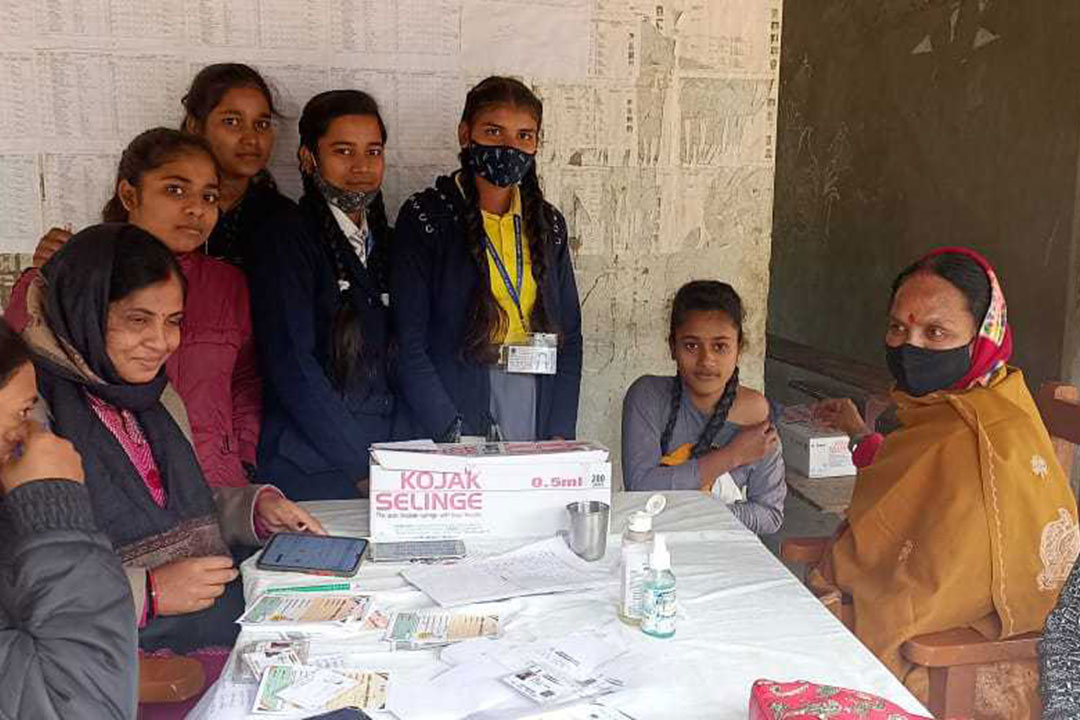

Credit: Muktaa Charitable

Looking forward

The primary focus in primary health care is always prevention. By vaccinating individuals, we can reduce those mental health issues that may arise secondary to vaccine-preventable diseases, at least. But across the board, raising awareness is crucial. Mental health becomes a priority only when people are aware of their struggles.

Agarwal further emphasised, "Efforts should be directed toward increasing awareness through campaigns in schools, colleges and tribal areas. Prioritising such initiatives is essential for ensuring that mental health is recognised and addressed where it matters most."

More from Aayushi Shukla

Recommended for you