Nine factors that could boost your risk of Long COVID

Emerging research is shedding light on why some people are more likely to develop persistent symptoms after catching COVID-19 than others.

- 28 January 2022

- 6 min read

- by Linda Geddes

In the two years since the WHO declared COVID-19 a public health emergency of international concern there have been more than 356 million confirmed cases, and at least 5.6 million deaths, while millions more continue to experience ongoing symptoms in a condition known colloquially as Long COVID.

It has been an enduring mystery why some people experience debilitating fatigue, brain fog, breathlessness or other symptoms for many months, whereas others quickly recover.

Many researchers believe that Long COVID may not be a single syndrome, so it is possible that different groups are more or less at risk of different types of persistent symptoms.

A precise definition of what constitutes Long COVID – also known as post-acute COVID-19 syndrome – has been difficult to pin down. Some researchers define it as COVID-19 symptoms lasting longer than 28 days, others three months. There is also disagreement about which, and how many symptoms are associated with the condition. This lack of consensus has led to differences in estimates about its prevalence, and who is most likely to be affected.

Even so, scientists are increasingly zeroing in on which groups are at greatest risk of developing persistent symptoms, and unpicking some of the biological mechanisms that could explain why. Doing so could lead to the development of biomarkers to predict which individuals are at high risk, as well as interventions to help hasten their recovery.

Here’s what we know so far:

1. Biological sex

Various studies have suggested that women, particularly those aged 40-60, are at greater risk of developing ongoing symptoms, such as fatigue, breathlessness, brain fog, muscle pain, anxiety, or depression, after their initial COVID-19 infection, compared to men. For instance, according to a study published in Nature Medicine, which drew on data from 4,182 COVID Symptom Study app users who consistently logged their health, 15% of women experienced symptoms lasting for 28 days or more, compared with 9.5% of men, although this sex difference disappeared among those aged over 70. The greatest difference between men and women was observed among those aged between 40 and 50, where women had double the risk of developing Long COVID compared to men.

Women are also more prone to autoimmune disease and ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis, or chronic fatigue syndrome). Researchers suspect there may be some overlap between these conditions and long COVID.

2. Age

The same study found that increased age was also associated with a greater risk of developing ongoing symptoms: More than one fifth (22%) of people aged over 70 reported symptoms lasting four weeks or more, compared to a tenth of those aged 18 to 49.

However, more recent research by the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) has suggested that Long COVID is more likely to strike people in mid-life. Here, Long COVID was based on individuals self-reporting that they had it. Based on this diagnosis, 1.3 million people in the UK (2% of the population) were experiencing Long COVID in December 2021, with the highest prevalence among those aged 35 to 69.

3. Pre-existing conditions

In a separate study, researchers at King’s College London examined anonymised data from 1.2 million primary health records across the UK together with 10 population-based studies involving 45,096 participants. This suggested that pre-existing poor mental health was associated with a 50% increase in the likelihood of reporting Long COVID, while asthma was associated with a 32% increase. Many researchers believe that long COVID may not be a single syndrome, however, so it is possible that different groups are more or less at risk of different types of persistent symptoms.

Have you read?

4. Multiple early symptoms

According to data from the COVID Symptom Study app, people who experienced more than five symptoms during their first week of illness were 3.5 times more likely to develop Long COVID, compared to those experiencing fewer symptoms.

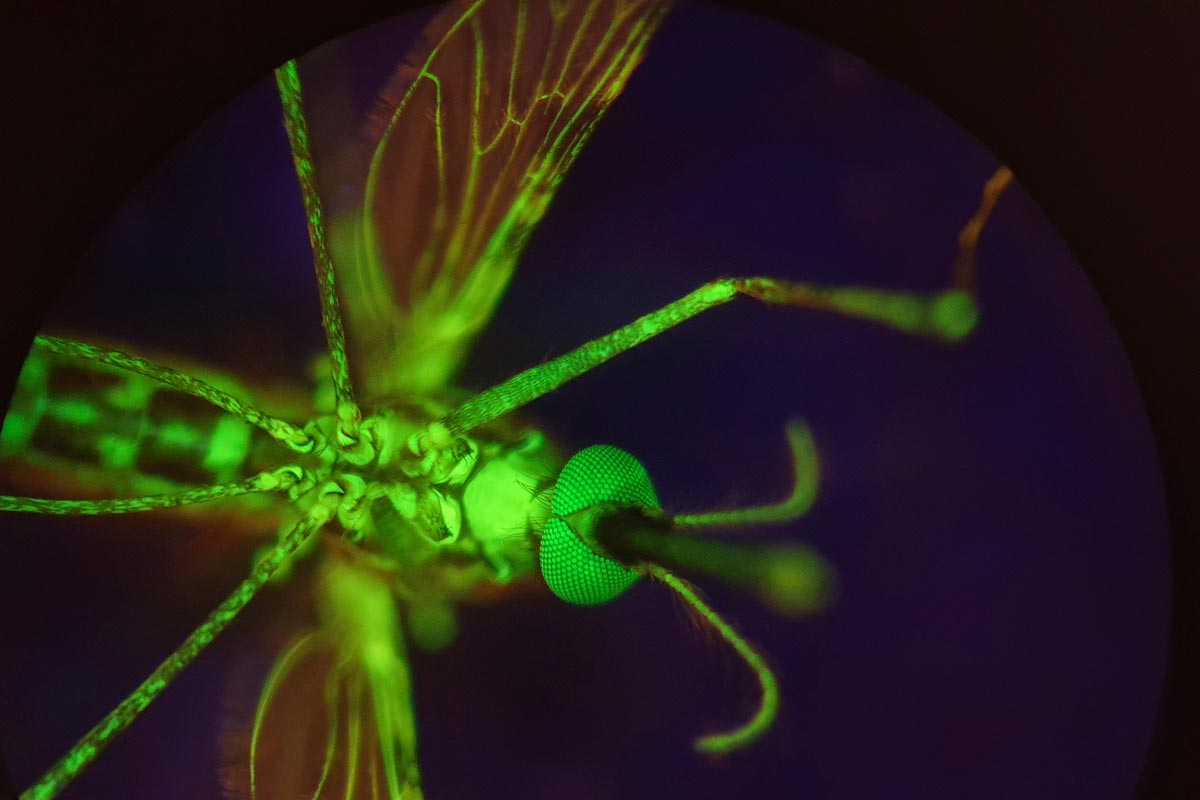

5. Viral load

According to new research published in the journal Cell, which analysed blood and nasal swab samples from 309 COVID-19 patients and correlated this with their symptoms in the following two to three months, those with higher amounts of virus in their bodies during the early stages of infection were more likely to develop persistent symptoms. One possibility is that they were exposed to a higher “dose” of virus to start with. Another explanation could also be that their bodies were less effective at controlling the infection once it got started.

One limitation of the study is that almost three quarters of the included patients were hospitalised, so it is unclear if the results apply equally to people who initially experienced milder COVID-19 infections. If high viral loads really are associated with persistent symptoms, then giving antiviral drugs soon after diagnosis could potentially help – although this would need to be tested.

6. Autoantibodies

The same study found that two thirds of patients who developed Long Covid had autoantibodies – antibodies that mistakenly attack the body’s own tissues – at the time of their COVID-19 diagnosis, and that as levels of these autoantibodies increased, protective SARS CoV-2 antibodies decreased. Early detection of such autoantibodies could potentially be used as a biomarker to predict who is at greatest risk of Long COVID. If autoimmunity is confirmed to play a role in the development of persistent symptoms, it may also be possible to intervene with existing therapies designed to dampen immune activity.

In separate research, doctors at University Hospital Zurich found that low levels of certain antibodies – including IgM, which is the first antibody we make in response to a new infection – were more common among individuals who developed Long COVID compared to those who recovered quickly. Combined with details about the patient’s age, initial symptoms, and whether they had asthma, this antibody signature enabled them to predict who had a moderate, high or very high risk of developing ongoing COVID-19 symptoms.

7. Previous Epstein-Barr infection

Another finding of the Cell paper was that the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which infects around 90 percent of the human population and usually persists in an inactive form post-infection, was reactivated early on after SARS-CoV-2 infection, and this was significantly associated with the development of persistent symptoms. This reactivation could possibly be related to the immune response to COVID-19.

8. Gut microbes

Our intestines are an incredible immunological organ, and the microbes living within it are able to tweak our immune responses. According to research published in the journal Gut, people with alterations in the variety and volume of these resident bacteria during their initial COVID-19 infection were at greater risk of experiencing ongoing COVID-19 symptoms lasting six months or more. Further studies should investigate whether modulating these microbes could facilitate timely recovery from Long COVID, the researchers said.

9. Vaccination status

Recent research published in The Lancet Infectious Diseases suggested that odds of developing symptoms that lasted longer than 28 days was approximately halved among people who became infected after being fully vaccinated. Further data published by the UK’s Office for National Statistics this week supports the idea that vaccination reduces the risk of Long COVID – although doesn’t entirely prevent it. It found that British adults who had received two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine at least two weeks before catching the virus had a 41.1% lower risk of reporting Long COVID symptoms 12 weeks later.