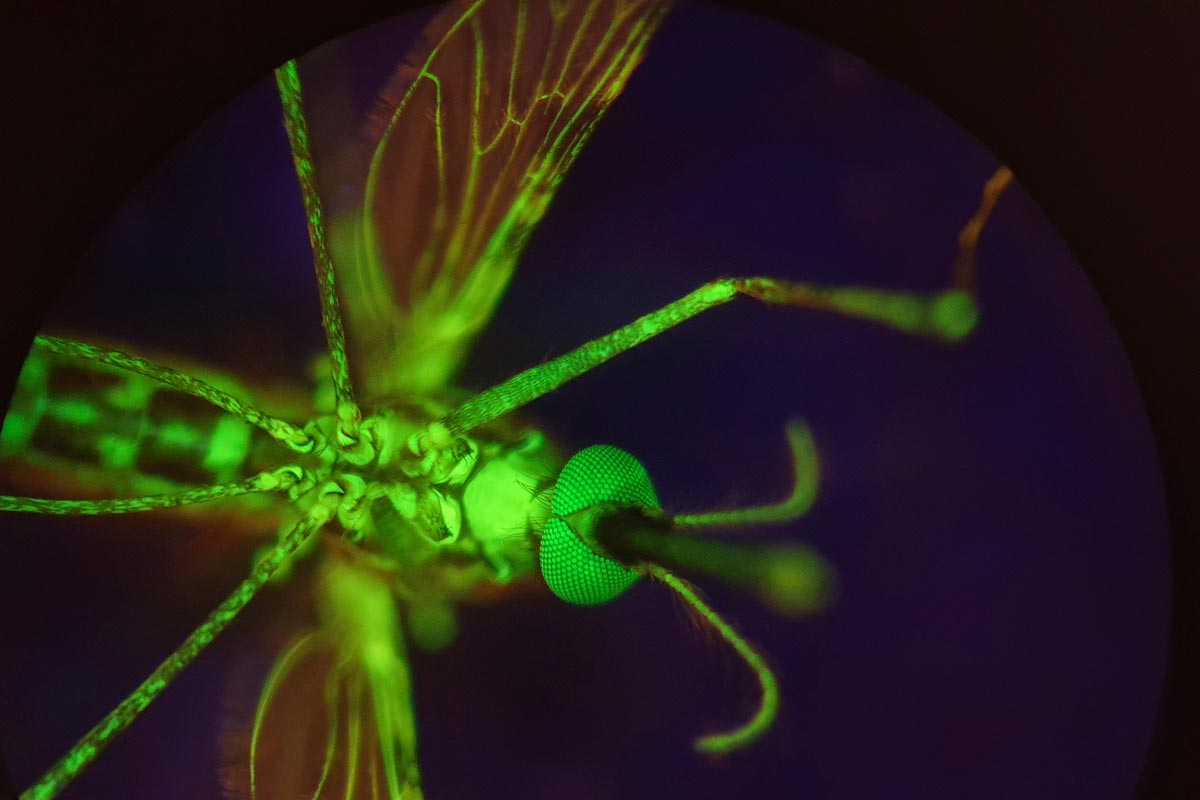

Could a drug make our blood toxic to mosquitoes?

Scientists have found that an existing drug used to treat rare diseases could also help to suppress mosquito populations and control malaria.

- 28 March 2025

- 3 min read

- by Linda Geddes

An existing drug could make our blood toxic to mosquitoes, helping to reduce their numbers in malaria-prone areas.

Avoiding mosquito bites is crucial in the fight against malaria. Currently, this is achieved through using bed-nets and insecticide spraying in high-risk areas, but insecticide resistance is increasing at an alarming rate.

Mosquitoes are also changing their behaviour to resist these interventions, avoiding indoor environments sprayed with insecticides and increasing outdoor feeding.

Lethal blood

Researchers have identified another potential tool: the use of so-called endectocides – antiparasitic drugs that can be safely given to people or animals, but which make their blood toxic to parasites and blood-feeding ticks or mosquitoes.

“Even when insects and ticks ingest sublethal doses, their life spans are reduced, thereby impairing the development of pathogens,” said Prof Lee Haines at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, US, who co-led the new study.

One such drug has already been identified: the antiparasitic medication ivermectin. Studies have suggested that when mosquitoes ingest blood containing ivermectin, it shortens their lifespan and helps decrease the spread of malaria.

However, the widespread use of this drug is problematic because it can accumulate in natural environments, potentially harming soil-dwelling creatures such as earthworms, which form a crucial part of ecosystems. Ivermectin resistance is also a growing problem.

A new solution

Now Haines and colleagues have identified another drug with the potential to suppress mosquito populations: nitisinone.

Typically used to treat people with rare inherited disorders who struggle to break down the amino acid tyrosine, nitisinone works by blocking an enzyme called 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD), preventing the build-up of harmful breakdown products.

The drug also blocks this enzyme in mosquitoes, where it has an additional superpower: it prevents mosquitoes from properly digesting blood, causing them to die.

The researchers investigated what concentrations of nitisinone would be needed to kill mosquitoes and how it would stack up against ivermectin as a mosquito control strategy.

Their research, published in Science Translational Medicine, suggested that nitisinone could potentially help to reduce the risk of malaria, when deployed alongside other strategies such as the use of antimalarial drugs, bed-nets and vaccines.

Have you read?

“Fantastic” performance

“We thought that if we wanted to go down this route, nitisinone had to perform better than ivermectin. Indeed, nitisinone performance was fantastic; it has a much longer half-life in human blood than ivermectin, which means its mosquitocidal activity remains circulating in the human body for much longer,” said study co-author Prof Álvaro Acosta Serrano, also at the University of Notre Dame and Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine in Liverpool, UK.

“This is critical when applied in the field for safety and economic reasons. What’s particularly interesting is that it specifically targets blood-sucking insects, making it an environmentally friendly option.”

In the future, it could be advantageous to alternate both nitisinone and ivermectin for mosquito control, according to Haines. “For example, nitisinone could be employed in areas where ivermectin resistance persists or where ivermectin is already heavily used for livestock and humans.”

The next step would be to conduct a semi-field trial to confirm which nitisinone dosages would be most effective in a closer to real-life scenario.