Nigerian 'sickle cell warriors' face new foe: climate change

Hotter, colder and more extreme weather is threatening all of our health – but sickle cell disease patients are on the frontlines of risk.

- 10 July 2024

- 7 min read

- by Afeez Bolaji

Living with sickle cell disease means that Chinonyerem Obianuju-Nwachukwu, from Port Harcourt, Rivers State, in southern Nigeria, is practised at managing her health meticulously. That includes taking special measures to avoid coming down with a pain crisis when the weather shifts.

"During hot weather, I put on something light and drink water that is just above room temperature. When the weather is very cold, I ensure I stay warm by putting on socks and footwear at home.

“Sometimes the weather can be unpredictable. It may be sunny when I'm leaving the house, but before I get to my destination, it's already raining heavily. During that period, I go out with a sweater and an umbrella," she tells VaccinesWork.

Nigeria is regarded as the epicentre of sickle cell disease (SCD), accounting for 4 to 6 million of the approximately 50 million people worldwide who live with the disease. About 100,000–150,000 children with SCD are born annually in the country, representing 33% of the estimated 300,000 newborns diagnosed with the disease globally every year.

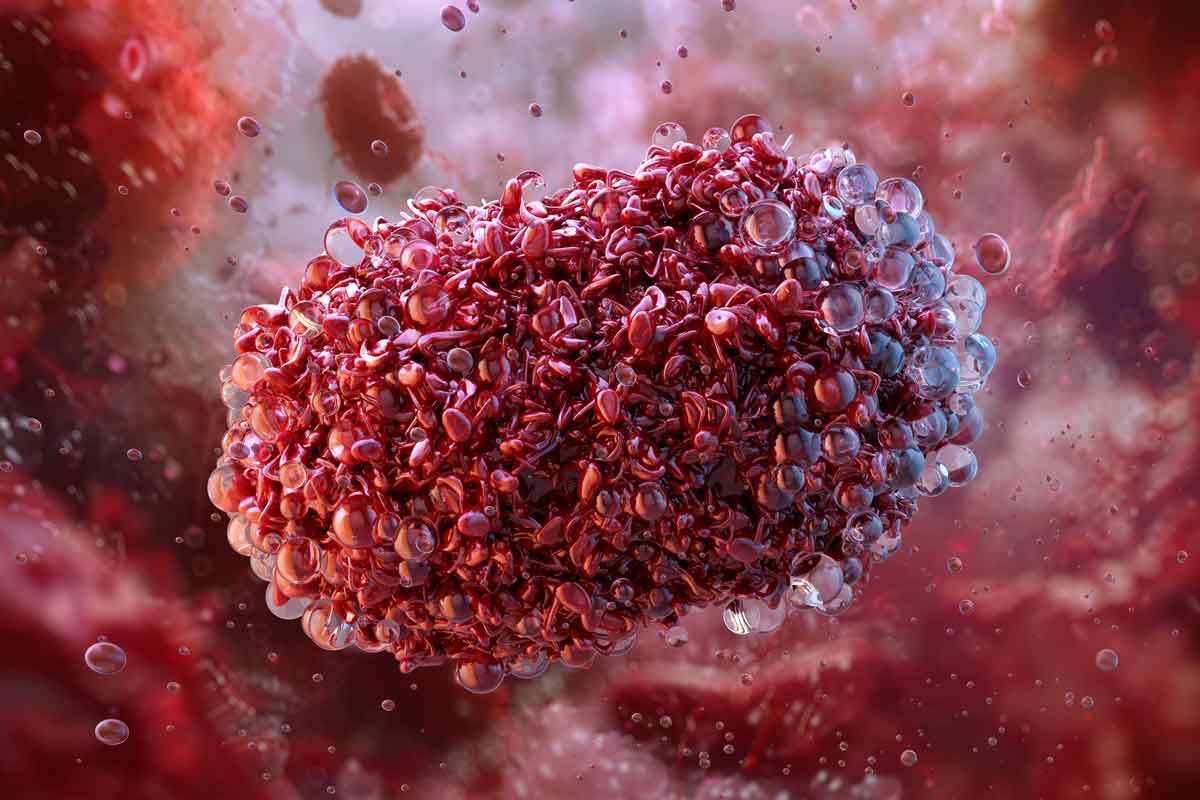

SCD is an inherited, life-long blood disorder characterised by deficient protein in red blood cells that carry oxygen to the tissues of the body.

The “sickled” red blood cells have abnormal crescent-like shapes, which can stick together, blocking up blood vessels. Sickled cells have shorter life-spans than healthy red blood cells, and SCD patients can, as such, be chronically anaemic. The sickled cells can also cause damage the spleen – the organ that filters waste in the blood – putting the person at greater risk of infections. Other SCD symptoms include “pain crisis”, which results from blocked blood flow to a part of the body, anaemia, jaundice and stroke. “Acute chest syndrome,” when sickling occurs in the chest, can set in when the body is under threat from infection or dehydration, and can be life-threatening.

“They are more prone to severe malaria, which is very problematic. Hence, sickle cell warriors are advised to be on prophylaxis to prevent malaria.”

- Dr Oluwole Banjoko, clinical haematologist

Weather forecast, or early-warning system?

Unpredictable weather brought on by climate change has compounded SCD management: Maureen Nwachi says she builds her day around the forecast.

Nwachi is a sickle cell “warrior” – a term favoured by many patients to discourage stigmatisation – as well as advocate and genetic counsellor at the Lagos-based non-profit organisation Sickle Cell Advocacy & Management Initiative (SAMI). "I regularly check weather forecasts to plan my activities and dress appropriately for the expected weather conditions. I maintain a flexible schedule to accommodate sudden weather changes, ensuring I can adjust my activities to minimise exposure to extreme weather.

"I keep in close contact with my health care provider and have a plan in place for emergency situations. Vector and waterborne diseases are worsening due to climate change, and they do impact sickle cell warriors.

"We are more susceptible to infections due to compromised immune systems. Malaria, in particular, poses a significant risk as it can trigger sickle cell crisis. I use insect repellent, sleep under mosquito nets and ensure that I consume clean, safe water," she reveals.

“Cold is particularly a difficult one. When the blood vessels are exposed to cold, they shrink, and the tendency for red cells to change to sickle shape and block those vessels is very likely. So they need to keep themselves warm.”

- Professor Philip Olatunji, consultant haematologist

Bad for us all, worse for SCD patients

Sickle cell patients’ heightened susceptibility to malaria has an element of grim irony to it: scientists believe that the sickle cell gene proliferated in parts of Africa because inheriting one copy of the faulty gene (coded “S”, for sickle) and one normal gene (coded “A”) increases resistance to malaria. But the advantage turns into a liability when two S genes are inherited.

“Genetically, SS [people] are prone to malaria unlike AS [people] which protects you from a malaria infection,” confirms Dr Oluwole Banjoko, clinical haematologist at the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital. “They are more prone to severe malaria, which is very problematic. Hence, sickle cell warriors are advised to be on prophylaxis to prevent malaria.”

Obianuju-Nwachukwu and Nwachi’s accounts echoed those of a cross-section of sickle cell warriors in Nigeria, who spoke to VaccinesWork.

Medical and climate research suggests that, as the increasing likelihood of extreme weather conditions heightens risks to human health, it disproportionately raises the chances of a crisis for sickle cell sufferers.

“Cold is particularly a difficult one,” says Professor Philip Olatunji, consultant haematologist at the Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital in Ogun State. “When the blood vessels are exposed to cold, they shrink, and the tendency for red cells to change to sickle shape and block those vessels is very likely. So they need to keep themselves warm,” he says, adding that he encourages sickle cell warriors to avoid strenuous tasks and take at least three to four litres of water per day to stave off risky dehydration.

“Some [sickle cell patients] may already be in a state of dehydration by virtue of the SCD. So when they lose water because of the cholera infection, it will affect them much faster than people without SCD.”

- Professor Philip Olatunji, consultant haematologist

As most parts of Nigeria begin to record rainfall, Olatunji advises sickle cell warriors to be more vigilant against infectious diseases like cholera, paying close attention to personal hygiene, and being more conscious of what they eat and drink.

Nigeria is currently battling cholera outbreaks, with 1,141 suspected cases, 65 confirmed cases, and 30 deaths reported in 30 states recorded in the first half of this year.

"Some [sickle cell patients] may already be in a state of dehydration by virtue of the SCD. So when they lose water because of the cholera infection, it will affect them much faster than people without SCD. They need to approach a hospital, because they may need to get water into their system quickly," Olatunji further warns.

Clinical haematologist Dr Banjoko says he always tells his sickle cell patients to bathe with hot water when it is cold, go out with "a big umbrella" in the rainy season, and to keep raincoats handy.

"When heat is extreme, they need to cool off. They can use warm water to bathe. They can get some fans or air conditioning, but they should ensure the air doesn't blow to them directly,” he explains.

Unhospitable planet

The trouble may be looming, but it’s also well underway: climate change has already significantly altered temperatures, confirms Debo Adeyewa, Professor of Meteorology and Climate Science and Director of the Doctoral Research Programme in West African Climate Systems at the Federal University of Technology Akure in Ondo State.

"When it is hot in southern Nigeria, it is hotter in the north, like Sokoto State. Around February and March this year, the temperature was soaring to 33° [Celsius] in the south, which was not normal, but it was even higher in the north. Such an extreme heat scenario is called heat stress, which affects the health of individuals and can be really serious for sickle cell warriors due to dehydration," Adeyewa explains.

Have you read?

Anthony Kola-Olusanya, Professor of Environmental Sustainability and former Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic Research, Innovation and Partnerships) at Osun State University, Osogbo, adds that changing environmental factors like temperature, humidity and air quality can also worsen the sickle cell crisis.

"The frequency and intensity of heatwaves in the Sahel region, like Sokoto State, are higher because of low vegetation. So the elevated temperature has the propensity to trigger the vaso-occlusive crisis, which is the hallmark of sickle cell anaemia, causing severe pain and organ damage.

"In the same vein, there is extreme cold weather in Jos, Plateau State, known for a near temperate climate, which is not characteristic of the Nigerian weather. Extremely cold weather can lead to vasoconstriction of the blood vessels and pose an increasing crisis to sickle cells.”

“The frequency and intensity of heatwaves in the Sahel region are higher because of low vegetation ... [That] has the propensity to trigger the vaso-occlusive crisis, which is the hallmark of sickle cell anaemia, causing severe pain and organ damage.”

- Anthony Kola-Olusanya, Professor of Environmental Sustainability

"In Sokoto, the intensity of harmattan dust is high. This can make breathing tough for sickle cell patients, thereby impacting their respiratory health. They need to cover their noses to filter the dust and breathe in clean air," the climate expert adds.

Kola-Olusanya notes that the intersection of climate and sickle cell anaemia is a unique challenge, urging those managing the patients to be more concerned about the support available to them. “The warriors need to be educated on how to adapt to extreme temperatures," he adds.

More from Afeez Bolaji

Recommended for you