Mapping vaccine confidence worldwide

Anecdotes of how people feel about vaccines are plenty, but there have been few attempts to gather robust global data. This five-year study reviewed survey responses from over a quarter of a million people around the world on how they felt about vaccines. This is what they said.

- 16 September 2020

- 4 min read

- by Priya Joi

Understanding vaccine confidence – and the reasons why people may not want a vaccine – is critical to ensuring vaccine uptake, and will be especially important if a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available. Although existing data systems are able to measure the number of people vaccinated, they often don’t routinely capture levels of vaccine confidence. Heidi Larson, Director of the Vaccine Confidence Project, and colleagues at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, in the UK, have published a paper in the medical journal The Lancet on the findings from surveys on vaccine confidence conducted over five years.

Vaccine confidence was highly related to a belief in the importance of vaccines, more so than perceptions of their safety or effectiveness.

The largest global survey of vaccine confidence

In this study, survey responses on vaccine confidence between 2015 and 2019 were examined, including 284,381 people across 149 countries. Common questions that respondents were asked included: whether they thought vaccines are safe, whether they are effective and whether vaccines are important for children to have. The researchers modelled the survey responses to identify trends and their key contributing factors.

Some of the surveys were undertaken as part of the Wellcome Global Monitor, which included other qualitative questions on trusted sources, information-seeking behaviours and whether respondents with children report having have vaccinated at least one child with any vaccine from a routine immunisation programme.

Shifting vaccine confidence across the globe

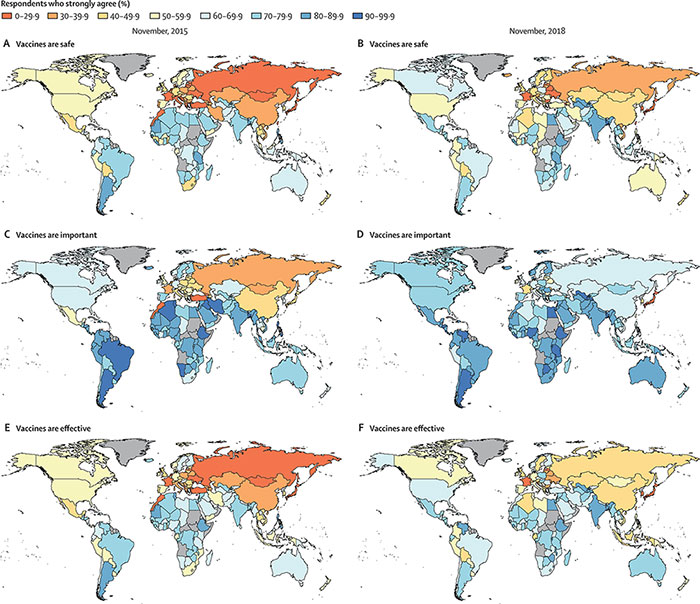

The map shows shifting responses over the study period.

The results indicate that vaccine confidence fell between 2015 and 2019 in Indonesia, the Philippines, Pakistan, and South Korea, and in Afghanistan and Vietnam.

Vaccine confidence increased over that time for France, India, Mexico, Poland, Romania and Thailand.

Have you read?

What affects confidence in vaccines?

Even when effective vaccines are available, people may not get vaccinated, or may delay it because of concerns about safety, or because they are worried about potential side-effects or the speed at which COVID-19 vaccines are being developed. Or they might be opposed to vaccination altogether. Others may have trouble accessing vaccines if they live in remote areas, or because vaccines are not made available to them. In addition to the significant challenges that many people in low- and middle-income countries already face in accessing routine vaccines, which should not be underestimated, the researchers found that vaccine uptake is also significantly correlated to vaccine confidence.

Vaccine confidence was highly related to a belief in the importance of vaccines, more so than perceptions of their safety or effectiveness. Factors leading to high vaccine confidence included trusting health care workers more than family or friends for medical advice; higher levels of science education; age (younger people are more likely to get vaccinated); and increased information-seeking behaviour.

The reasons for a fall in confidence can be varied. In the Philippines, for instance, confidence in vaccines had been dented by concerns over a vaccine against dengue virus. Individuals who had received the Dengvaxia vaccine without previously having been infected by one of the four types of dengue virus were at risk for more severe disease if they later developed dengue. This damaged public confidence in the broader immunisation programme because nearly 850,000 children had been given the new dengue vaccine the previous year. In Malaysia, Poland and South Korea meanwhile, drops in public confidence were linked to well-organised anti-vaccination campaigns. In Japan, low vaccine confidence was linked to concern over the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine.

Falling confidence in Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, Pakistan and Nigeria aligns with growing political instability and religious extremism. Additionally, in Pakistan and Nigeria misinformation about polio vaccines has been circulating, which led to a rise in cases of polio in these countries.

Improving vaccine confidence

Combatting a lack of vaccine confidence is a complex task. Nevertheless, the researchers say that having a common metric of confidence and a baseline for comparison will be important to measure these changing trends. These markers can serve as a kind of “early warning system” of a potential decline in vaccine confidence and alert countries to the need to implement approaches to rectify it.

It is important to note however, that what people say does not necessarily correlate with what they do. The outcome that is important in preventing disease and vaccination coverage - trust in vaccination - is a useful but not always reliable influence on those outcomes. For example, making vaccination mandatory for school attendance has helped improve coverage and decrease disease in many areas.