Ye Olde Anti-Vaxxers

As long as there have been vaccines, a vocal minority of public voices have made it their mission to rile up their communities against vaccination. In Montréal, in 1885, those voices were successful – and the results were deadly.

- 14 April 2021

- 5 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

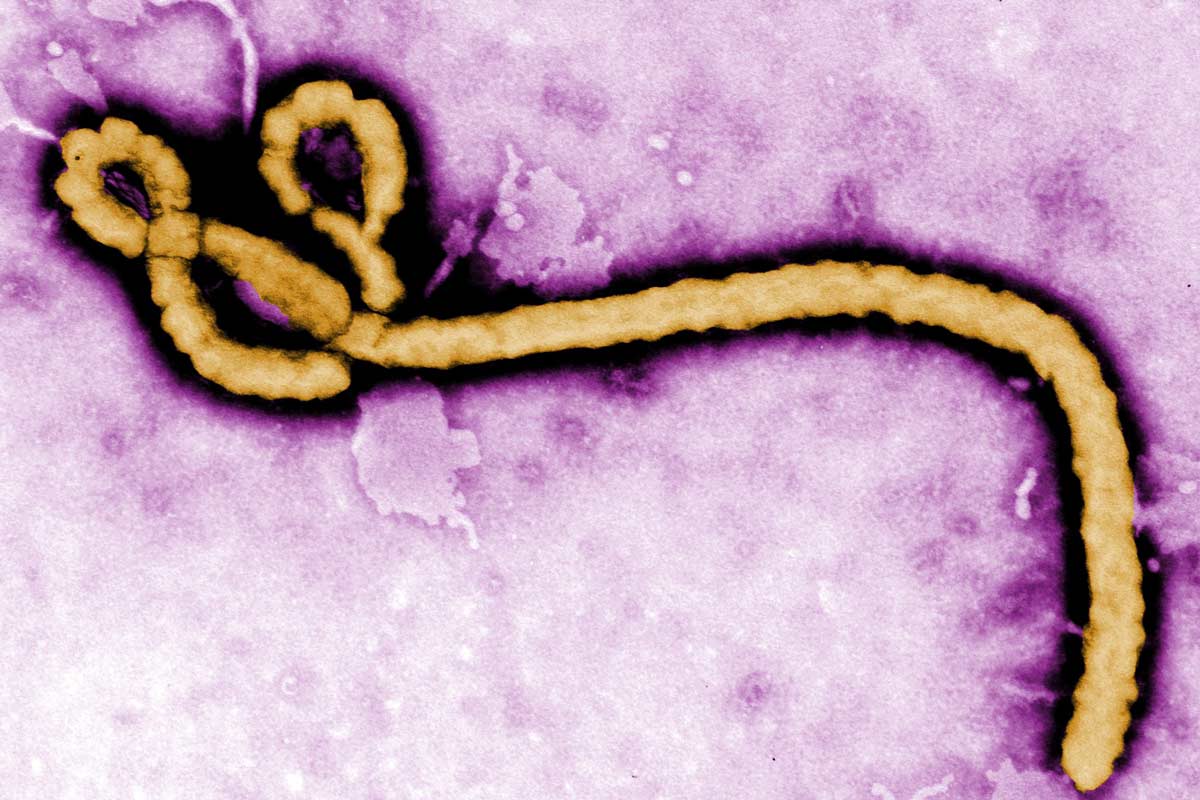

In March 1885, a train from Chicago arrived at Bonaventure Station in Montréal with a particularly dangerous passenger: smallpox. George Longley, train conductor, feverish and boiling with pustules, found a bed and medical care at the Hôtel-Dieu. Longley recovered, but not before a laundry-maid named Pélagie Robichaud caught the disease from his contaminated linens. She died on April 2nd. Her sister soon followed. By late summer, smallpox was everywhere. In November, when the epidemic finally burnt itself out, nearly two percent of Montréal’s population had been killed, and many more had been blinded and scarred. Most of the victims were children.

Had Little been able to foresee the tail-end of her century, she might have been surprised to learn that vaccination – an “egregious failure,” as a pamphlet she published in 1918 described it – had eradicated smallpox altogether.

The vaccine first tested and described by Edward Jenner in 1796 was by now nearly a century old, widespread and well-established. Why did Montréal remain so vulnerable to a reliably preventable sickness with fatality rates of up to 40 percent? The answer is that there was another epidemic taking hold: in Montréal, an outbreak of hesitancy was outpacing the disease. Resistance to vaccination was particularly pronounced in the city’s east, a zone inhabited predominantly by typically poorer French Canadians – at the end of the year, French Canadians would make up 90 percent of the dead.

Anxiety about vaccination was then, as it is now, the product of a complex cocktail of politics and social forces, deeply held beliefs and misunderstandings of medical advances that struck many people as counter-intuitive. It didn’t help that in Spring, a contaminated batch of vaccine caused patients to break out in skin infections, after which efforts to vaccinate Montréal and stem the spread of smallpox were briefly halted.

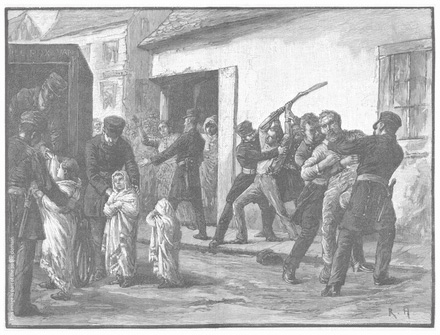

Then, as now, campaigning anti-vaxxers made it their business to whip up worry into a movement. When the Board of Health announced in September that smallpox vaccination was to be compulsory, rioters descended on the East End Branch Health Office.

This image is part of the public domain.

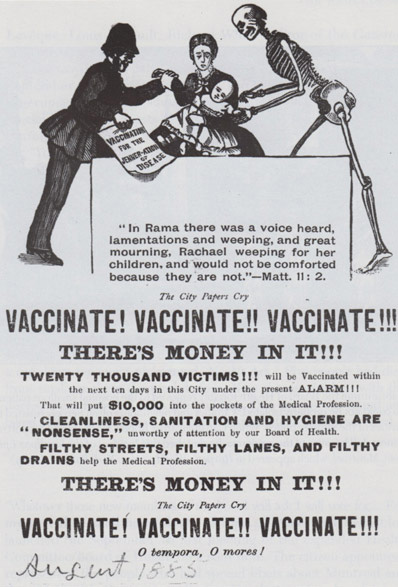

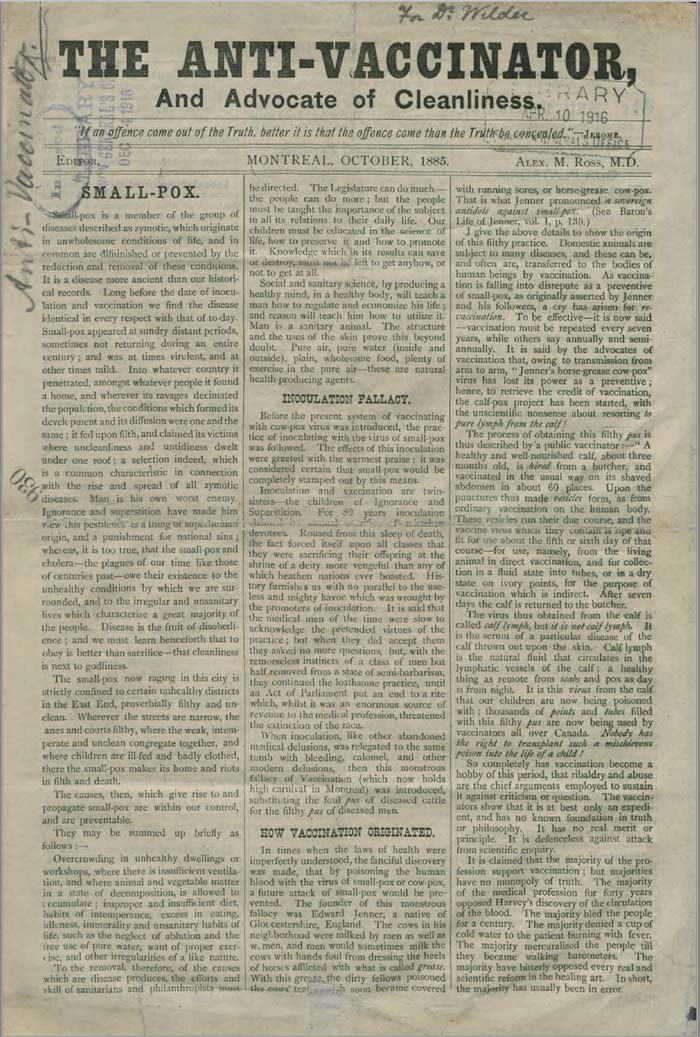

Disinformation, it turned out, spread readily enough in either language. A particularly strident voice belonged to Dr Alexander M. Ross, physician, and editor of “The Anti-Vaccinator.” Ross’s position, as he described it, was that “vaccination is useless and dangerous”; that rather than protecting patients from smallpox, it “produces its like”; and that vaccination was “a fearful engine of destruction and death to children”. During the 1885 epidemic, a pamphlet authored by Ross circulated widely. It urged refusal, derided the vaccinated as “driven like dumb animals”, and insisted categorically that “vaccination does not prevent Small-pox in any cases.”

Image source: M. Bliss, Plague: The Story of Smallpox in Montreal (Toronto: HarperCollins, 1991) (Public domain image) |

|

Strange, then, that Ross had quietly chosen to get himself vaccinated that year, as the epidemic raged – a fact “gleefully reported”, according to medical historian Paula Larsson, by the newspapers of the day.

Larsson has described anti-vaxxers of Ross’s type as “white knights” – opportunists, keen to be regarded as heroes. As Montréal’s public health authorities strove to spread vaccination to contain the smallpox, “Ross seized on the opportunity of increased health measures to gain authority, notoriety and personal fame,” she writes.

Have you read?

If that sounds familiar, his methods will too. As Larsson explains, Ross’s chief rhetorical moves were strikingly similar to the lines pushed by modern anti-vaxxers. Ross scoffed at the alarm of public health custodians as “senseless panic”, peddled conspiracies about the cynical greed of the medical establishment, grossly exaggerated the risks of contaminated vaccine batches, appealed to a sense of violated personal liberty, and leaned heavily on the “evidence” produced by the minority of doctors who shared his position.

Through the second half of the 19th century, Montréal’s wasn’t the only community to lose lives to the successes of anti-vaccine activism. In the United Kingdom in 1853, smallpox vaccination was made mandatory for babies under three months. Increased pressure from the authorities crystallized resistance to vaccination: protests and riots followed, and an Anti-Vaccination League was established in London that same year. Similar outfits sprang up in mainland Europe, finding profound influence in Stockholm, where, by 1872, vaccination rates plummeted to 40%, compared to an average 90% vaccination rate across the rest of Sweden. In 1874, the smallpox came to Sweden and 4,063 died, with fatalities disproportionately concentrated in the capital.

Vaccine science made gain after gain at the turn of the 20th century, but the anti-vaccine movement persisted. One influential agitator, Lora C. Little, published “the Liberator,” an anti-vaccine monthly, in Minnesota between 1900 and 1905. The origins of Little’s crusade were personal: her son, Kenneth, had died aged 7 in 1896. His cowpox inoculation – a prerequisite for joining school in Yonkers, New York – had taken place more than half a year before his death, but Little was convinced it had killed him.

Had Little been able to foresee the tail-end of her century, she might have been surprised to learn that vaccination – an “egregious failure,” as a pamphlet she published in 1918 described it – had eradicated smallpox altogether. Instead, Little’s campaigning helped bring in new Minneapolis legislation in 1903 removing the obligation to be vaccinated against smallpox before attending school. The resulting smallpox epidemic infected 28,000 people. Then, as now, the true consequences of misinformation couldn't be seen until it was too late.