From Kraken to Pirola: who comes up with the nicknames for COVID-19 variants?

Professor Ryan Gregory is part of the team of COVID-19 sleuths who propose unofficial nicknames for Omicron variants.

- 9 October 2023

- 6 min read

- by Linda Geddes

According to the official naming system devised by the WHO, the Omicron variant is still the dominant form of COVID-19 worldwide. However, with new subvariants now springing up on a regular basis – the most recent of which is causing cases to spike worldwide – a group of scientists have taken up the mantle of giving us an unofficial way of describing these new lineages. VaccinesWork spoke to Professor Ryan Gregory, who works with this team of professionals and skilled amateurs.

What's wrong with the official naming systems for COVID-19 variants?

The reason the WHO developed the letter system and launched it in May 2021 was firstly, because people were using place names, such as the 'UK variant' or the 'South Africa variant', and there were worries about stigma and unnecessary travel bans. Secondly, the Pango labels were getting confusing, even pre-Omicron when there weren't that many variants. Already was there was a sense that people were getting lost.

Most of the discovery of new variants, informing the world about them and characterising them, is increasingly being done by this fairly small handful of people, who do not necessarily have a formal training in biology, but are now some of the world experts

– Professor Ryan Gregory

The Pango system is quite ingenious; it gives a lot of information and the folks who developed it had the foresight to create this ancestor descendent indication – which is why you get this letter-dot-whatever-dot-whatever format, e.g. BA.2.86, which tells you about the variant's ancestry. So, that's very useful, but it makes things significantly more challenging when there is so much evolution, and so many variants.

The WHO named everything they've named within 180 days: the last one was Omicron in November 2021. Omicron is now this massive group of very divergent lineages – there are about 1,700 Pango lineages – and yet they're all still called Omicron.

Why do you think there's a need for nicknames?

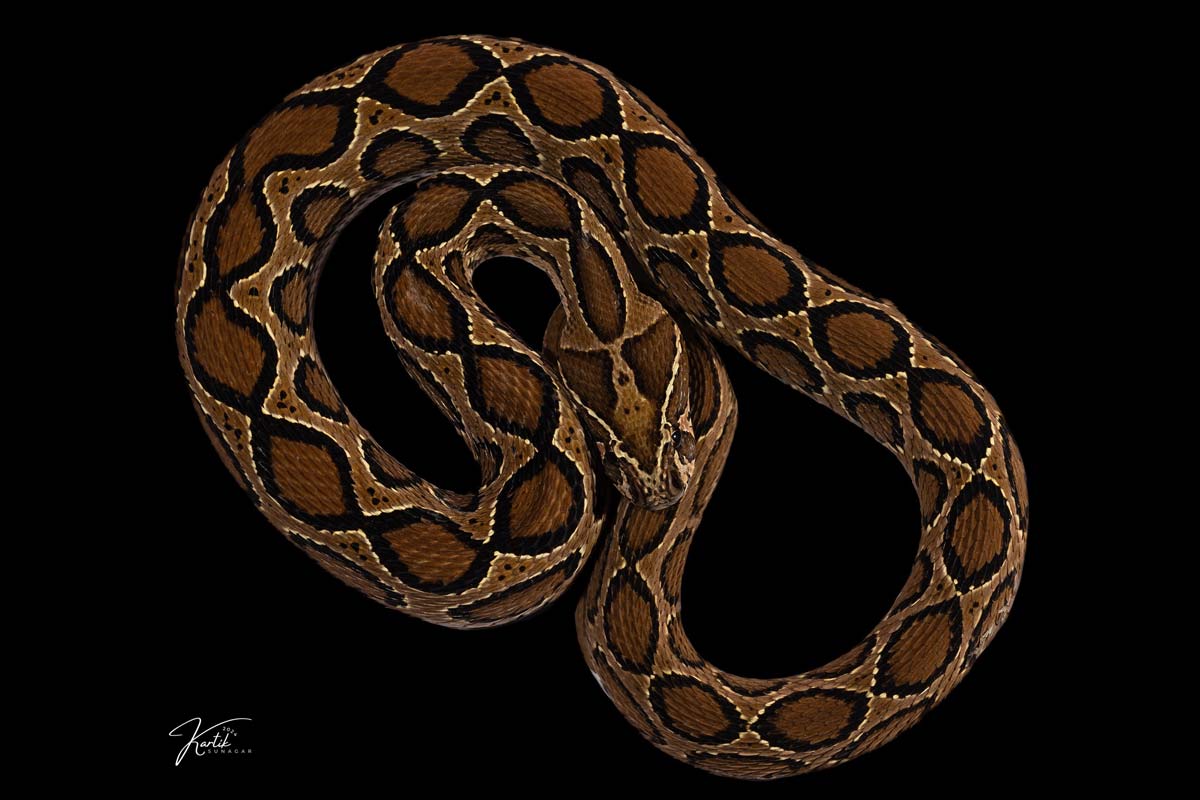

The analogy I've used is with common names in in zoology or botany. Omicron is like the high-level taxonomic class, and Pango lineages are like the Latin species names. For example, if you said, "What's making that noise in the woods over there?" and I said, "Mammal," you might ask me for more information, to which I might say, "It's Mus musculus." That wouldn't be helpful to most non-biologists, but if I used the common name – "mouse" – it would.

We use common names to talk about the handful of animals and plants that are most important to us. There are millions of formal Latin species names and these are useful in technical discussions, but every culture has a set of common names to easily communicate about a subset of things that are important. That's what's missing in the conversation about COVID-19 variants now.

Have you read?

What prompted you to start proposing nicknames?

It's not just me; there's a group of scientists and citizen scientists who work together to keep track of how SARS-CoV-2 is evolving, by analysing the genetic sequences that get uploaded from COVID-19 testing laboratories around the world. Most of the discovery of new variants, informing the world about them and characterising them, is increasingly being done by this fairly small handful of people, who do not necessarily have a formal training in biology, but are now some of the world experts as far as I'm concerned.

Many of the same folks are involved with the nicknames. It started very informally back in August 2022, which is when it started to become really complicated to talk about, because you've got dozens of variants circulating at the same time. I said, if the WHO isn't going to use Greek letters for any of these anymore, what about Greek mythological creatures? There's lots of them, many are familiar through popular culture, and so we kind of started doing that informally. WHO had actually considered Greek gods, constellations and other options before settling on Greek letters.

When we give something a nickname, it is because we think people are going to be trying to talk about it, and it is a simpler way of communicating. If that’s useful to people, they can use the nickname. But if you don’t like Pirola, you can call it BA.2.86, or Omicron, or even SARS-CoV-2.

– Professor Ryan Gregory

The one that really took off was Kraken, which isn't actually Greek, it's Scandinavian. I think the reason it took off is because it is so prominent in popular culture: there's a US ice hockey team, Seattle Kraken; a brand of rum; a cryptocurrency; it features in one of Disney's Pirates of the Caribbean movies. It was actually about the 20th variant that we had nicknamed, but it was the one that really caught on.

More recent nicknames have had an astronomical theme. Why?

It was partly in response to critical feedback that names like Kraken might cause unnecessary fear. We said, okay, we'll switch to astronomical names. Everything since then has been either a star, or a planet, a moon, a constellation, or what have you. The latest nickname, Pirola – which is for the BA.2.86 variant – is an asteroid. We didn't decide to nickname this variant because it had become widespread, but because it's got 30 mutations; it's a big departure from what's out there currently. We liked the idea of having Pi in the name, because the next Greek letter would be Pi, and the one after that would be Rho – so it's Pirola.

How do you decide which variants deserve a nickname, and how do you choose them?

I think the standard for nicknames is essentially, are people going to need to talk about it outside of technical discussions? Is there a need for easier, more accessible communication about this variant? It doesn't mean we think this is going to cause a huge wave or anything like that, it just means that this is probably one that people are going to be writing about or talking about – and trying to distinguish from other things that are already out there.

There tends to be a lot of discussion within the group about whether something needs a name, what to name it, when it's time. We might say, here's one that looks like it's either got a very significant growth advantage, or it's got these interesting mutations that make it notable. Should we consider a nickname?

What would you say to people who think we should just stick with the official system?

Some people have argued that if you name every variant that comes out, it is like crying wolf. But there's a very strong overlap between the variants we've nicknamed and what WHO has designated either a variant under monitoring (VUM) or a variant of interest (VOI). Sometimes the nickname comes first, but more recently WHO has named VUMs before we felt comfortable giving them a nickname.

When we give something a nickname, it is because we think people are going to be trying to talk about it, and it is a simpler way of communicating. If that's useful to people, they can use the nickname. But if you don't like Pirola, you can call it BA.2.86, or Omicron, or even SARS-CoV-2. You always have that choice, and most of us use both the nickname and the technical name in our tweets .

T. Ryan Gregory is an evolutionary biologist at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada