Going the extra miles in rural Nigeria to find children missing vaccines

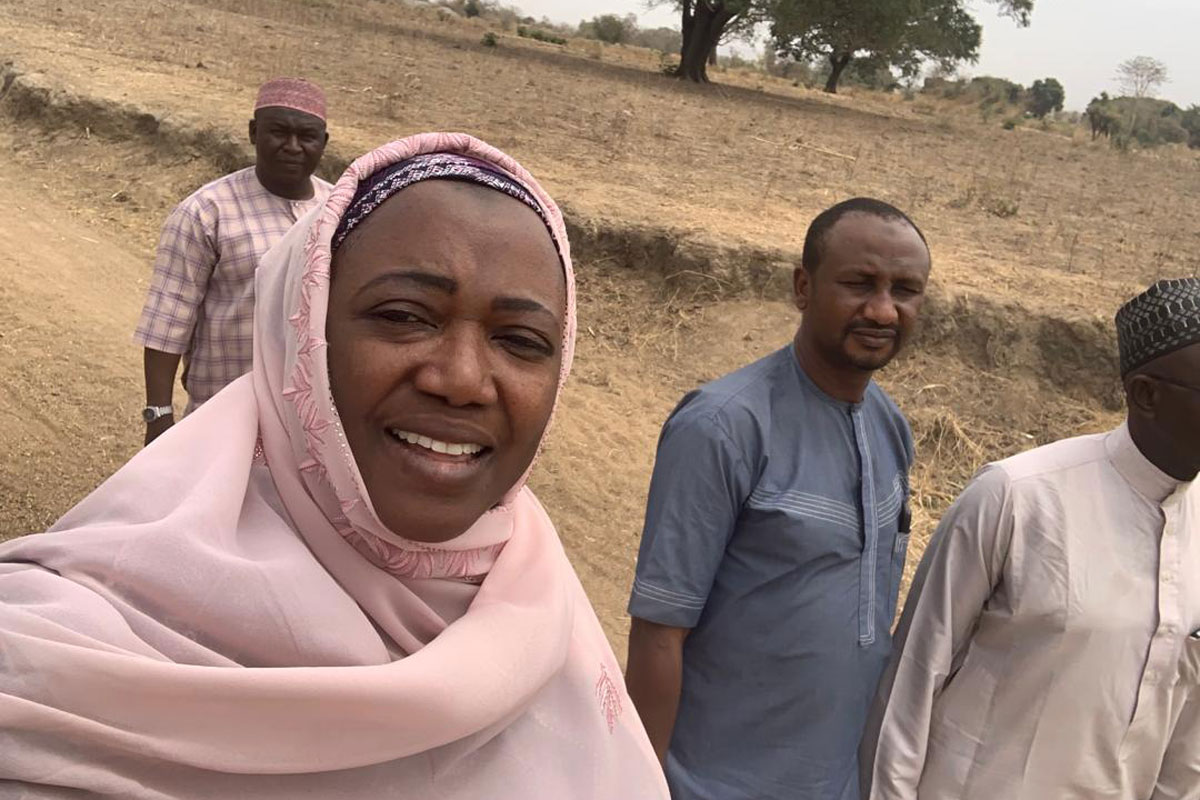

Alawiyatu Usman Ibrahim, a midwife, nurse, and BOOST member in Nigeria, shares how she developed a system to immunize infants in Bauchi.

- 6 August 2024

- 4 min read

- by Sabin Vaccine Institute

In her more than three decades as a midwife, then nurse and district coordinator for the Expanded Program on Immunization for the Nigerian Primary Health Care Development Agency, Ministry of Health, Alawiyatu Usman Ibrahim spent a great deal of time traveling throughout her native Bauchi state. She knew how to address issues and barriers to turn vaccines into vaccinations.

So, when the COVID-19 pandemic hit the west African nation, she also knew that the resulting shortage of recorded births in the state had to be incorrect.

She was right.

A member of Sabin’s Boost Community of global immunization professionals since 2021, Ibrahim had taken several online Boost courses that she credits with improving her ability to respond to immunization challenges. She signed up for the COVID-19 Recovery for Routine Immunization Programs Fellowship offered by the Sabin Vaccine Institute and the World Health Organization last summer, and developed a plan for a fellowship that would help her set up a system to find the infants who had been missed – and discover where vaccinations were needed.

Over the next few months, she and her team would find and vaccinate 300 children who were either zero-dose (defined as having had no diphtheria/pertussis/tetanus vaccine, one of the markers of childhood immunization) or “defaulters” — those who had missed subsequent childhood vaccinations — in just two of the wards she managed. She would also establish a reconciliation system that is now being used to find children in the other wards of the 96 settlements she oversees.

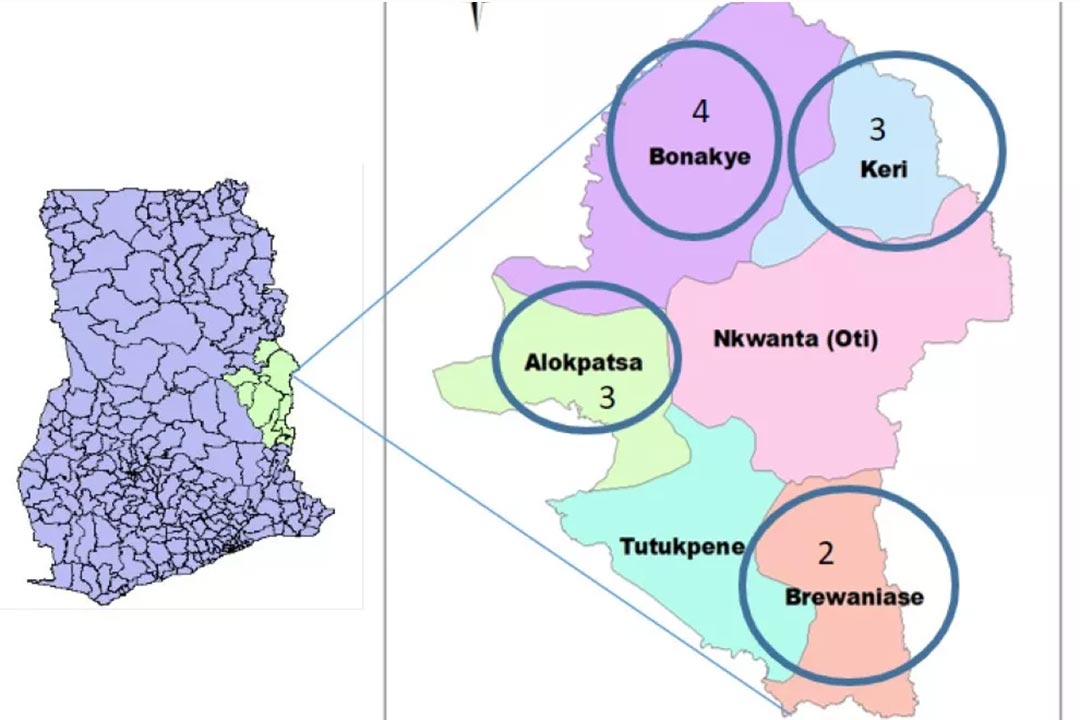

As one of the 60 fellows chosen for the implementation phase of the fellowship, where fellows were supported by mentorships and microgrants, Ibrahim began in early 2024 to identify which records needed updating in one ward in the north (Melendige) and one in the south (Mum-mun-sal) of Bauchi state. “Both wards have nomadic populations, but they look very different,” she says. “We wanted to develop a system that would work in both areas.”

“If we don’t have the actual number of zero-dose children, then we don’t know what to prepare for,” she says. “Normally we use existing structures on the ground, but this required expansion, and we can’t afford to expand. The fellowship allows us to set up the groundwork for this project. “

That groundwork included identifying which settlements would be targeted for reconciliation of the number of births and “defaulters” – those who had missed immunizations after the initial dose.

Ibrahim traveled with program officers to the health facilities in the settlements. “We told them our intentions (to count births and immunize those who needed it), and we began reconciliation. The head of the village or the religious leaders met with the health facility registrar, and we checked both registers against each other for ‘reconciliation’ so that each birth was recorded.”

At the same time, Ibrahim organized female volunteers to go door to door, a process she calls “mama to mama” – because women (and not men) can enter households where other women are and count children who may not have been recorded. “It helps add to the birth count,” she says. “In the house you find there are additional households, where younger brothers have married and had children. We make certain all new babies are noted in the community register.”

In order to set the stage for immunizations, the next step is sensitization – gathering the heads of villages, religious leaders, youth and women’s group representatives to discuss community activation and engagement. “You have to ask why there are defaulters,” she says. “Some reasons include the fear of side effects – children who receive the immunization may spend the whole night crying, so the household says do not take them back. Other times it is too expensive to go to the health care facility.”

The sensitization, says Ibrahim, is critical. “We can explain that these are killer diseases. We can have the leader of the community bring their own children for vaccination, to show it is safe.”

Have you read?

Ibrahim also learns from these sensitization sessions. “We have learned how important it is to communicate about when the service provider will be coming to the catchment area. We ask when the wives can join the men. We ask when it’s the best time. If you work with them, allow them to give you time and location, they give you much more cooperation.”

Ibrahim is happy with the results of the fellowship project. In March and April, the team traveled to wards in both the north and south and identified 117 zero dose children and 181 defaulters who were subsequently immunized. And now that they have strengthen the reconciliation method, “we have a process to use going forward in all areas of the state, and a mitigation method to address issues and gender barriers.”

This spring, Ibrahim received an award from Bauchi state for 35 years of active service in the State Primary Health Care Development Agency (Ministry of Health).