This small Nairobi clinic learned to listen, and vaccination rates went through the roof

Health workers used to struggle to reach the more than 8,700 eligible kids of Lindi Ward, in Nairobi’s massive Kibra slum, with vaccines. Not anymore.

- 8 July 2024

- 6 min read

- by Joyce Chimbi

When the Beyond Zero Clinic in Lindi Ward, part of Nairobi’s sprawling Kibra informal settlement, opened its doors in 2014, you were far more likely to encounter children in local nursery schools who had not received their very first vaccine than children who had, says nurse-in-charge Regina Atieno.

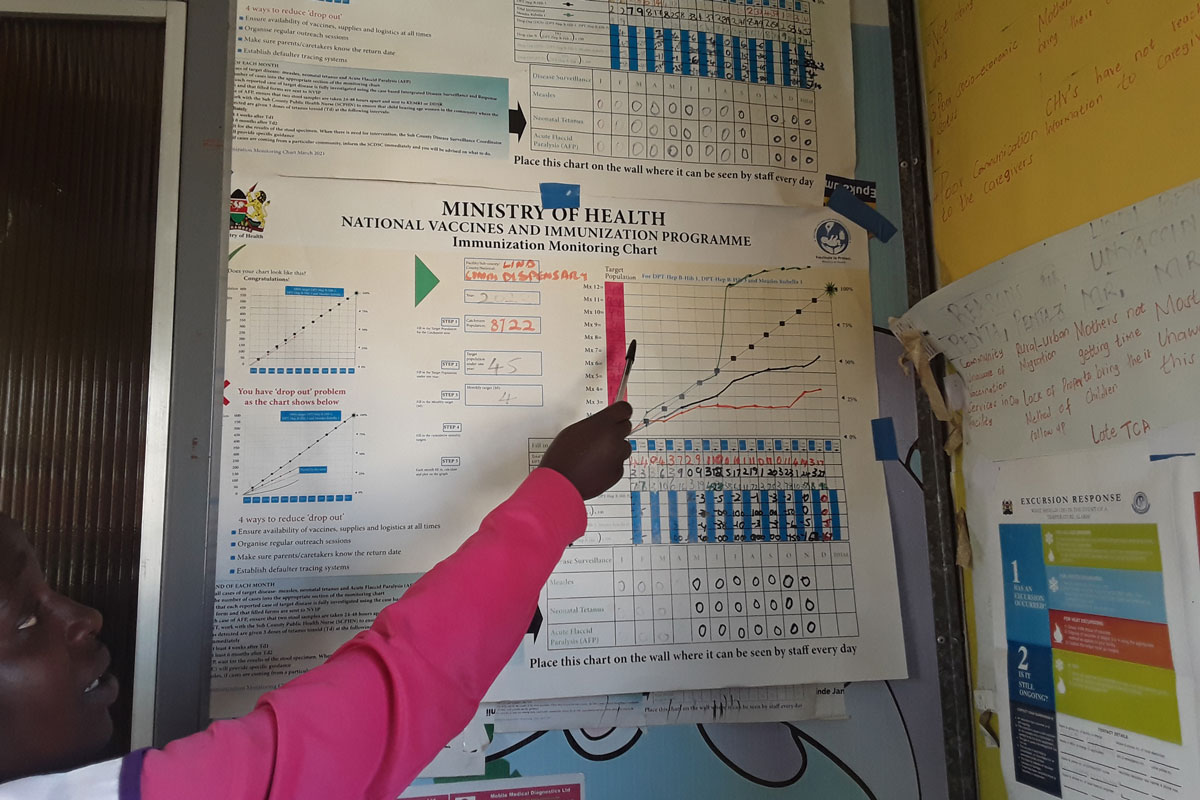

Indeed, a decade ago, immunisation coverage rates across Lindi Ward, home to an estimated 40,600 people, stood at about 20%. Today, recorded coverage stands at over 100%, meaning that the clinic is managing to serve additional children from surrounding neighbourhoods.

“[...] the Beyond Zero team is well known in this community and we trust them. We believe they are helping us, and they are, because you will rarely hear of a child’s death in our village.”

- Fey Barasa, mother, Lindi Ward

The clinic is small: three small rooms and just three staff members, one of whom is a volunteer. But Atieno, a veteran with 33 years of caring for hard-to-reach communities under her belt, says that brick and mortar assets are not always the ticket when it comes to reversing immunisation trends. Here in Lindi, she says, transformation was driven by a shift in communication.

Listening and looking

Building better interpersonal communication for immunisation doesn’t need to be complicated, and it isn’t expensive, Atieno says. It is time consuming – but in her experience, can make a massive impact.

It involves gathering information about the community being served, building a profile of the barriers that stand in the way of their children getting vaccinated, and engaging families in conversations to help build trust in the immunisation programme.

Those barriers are deeply specific to the community in question. Atieno speaks of the intersection between poverty and religion, and the negative impact that can have on immunisation. In Kibra, for instance, religious sects such as the Luo Church, Akorino and Legio Maria have large followings and they often discourage close interactions with modern health systems due to their strong ties to indigenous traditions.

Fey Barasa is a member of the Luo Church, which has strict rules around newborns. They “are not to interact with the outside world for the first 40 days of life. We keep babies behind closed doors and after 40 days, the child is brought outside in a very big celebration,” Barasa explains.

But the highest risk of death lies in a baby’s first 28 days of life, the so-called “neonatal period”. In Kenya, neonatal deaths account for 66% of all infant deaths and 51% of under-five deaths.

Atieno says once the baby misses the first dose of vaccine, and the days go by, that child can wind up slipping through the public health system’s net – and end up starting their school life without a single vaccination. There, they may be exposed to serious and deadly vaccine-preventable infections like tuberculosis, measles and rotavirus diarrhoea.

Barasa adds that fears of witchcraft and superstition around newborns can mean parents “refusing to take a baby to the hospital if they have sores in the mouth. My community believes that sores can be thrown into a baby’s mouth by jealous people. The baby cannot breastfeed and we cannot go to the clinic for any services at that time for fear that the nurse will insist on treating the baby. We fear the baby could die, because they are only supposed to be treated using herbs from the village.”

She nonetheless affirms that her two young children are on track with their vaccination schedule, “and it is all because the Beyond Zero team is well known in this community and we trust them. We believe they are helping us, and they are, because you will rarely hear of a child’s death in our village.”

Mercy Anyango, a member of the Legio Maria sect, says that due to the clinic’s child health awareness-raising efforts, “I’m able to ignore [religious] teachings that go against the well-being of my baby. I grew up in the church, but times are changing, and we have to leave behind practices that are harmful, like refusing to go to the hospital because doing so is seen as a lack of faith.”

In this context, Silas Cephas Oloo, a health official in Nairobi County, says building, staffing and providing medical resources is as critical. But with “marginalised and vulnerable communities, there is a constant need to look at the entire health ecosystem. A hard-to-reach population could mean communities in far-flung remote areas who have no access to health facilities.”

A community might also be difficult to reach because certain prevalent mindsets, beliefs and socio-cultural values undermine people’s receptiveness to health services, even when brought to their doorstep and free of charge, he explains.

Speaking up – and being heard

Beatrice Njeri, a nursing officer, says the Lindi clinic organises regular outreach sessions to speak to the community about the importance of child immunisation, track records to ensure that parents and caregivers know about their immunisation return date, maintain an up-to-date defaulter tracking system, and follow up to ensure that those who drop out return before too much time has passed. They also ensure that rural-urban migrants with young children are linked to the health facility without delay.

“One of the barriers to mass child vaccination campaigns was parents leaving strict instructions that their children are not to be vaccinated in their absence. But when you build strong relationships with the community, they trust that you are always acting in their best interest and this helps defuse vaccine resistance or hesitancy,” Atieno says.

Have you read?

Tallying impact

The Lindi clinic’s approach has been so successful that it has, in its zone of operations, overcome challenges dogging the national immunisation programme, including a low coverage with the second dose of measles vaccine. Ministry of Health data shows that the national coverage of the first dose of measles is 89%, while the second hovers at 66.8%.

According to the clinic’s routine immunisation records, which are populated in line with the Ministry of Health guidelines, within the clinic’s child immunisation catchment area, not only has the Lindi clinic surpassed a 100% coverage of the second dose of measles , its Vitamin A supplementation coverage for children aged 6 to 59 months is similarly on target.

Furthermore, according to the Clinic’s disease surveillance records, in recent years, they have had zero cases of measles, cholera, neonatal tetanus and acute flaccid paralysis – a very serious neurological condition that can point to a number of underlying causes, including viral infection. There have also been no childhood deaths linked to diarrhoea.

Despite cervical cancer being the second prevalent and leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women in Kenya, some influential religious voices have spoken against the cancer-blocking HPV vaccine. In Lindi, the clinic has leveraged its strong links in the community to vaccinate 384 adolescent girls, against an initial target of 32 girls.

The Beyond Zero Lindi clinic is one of many Beyond Zero Clinics rolled out in 2014 as part of a government initiative responding to unmet health needs in hard-to-reach communities, with the specific target of bringing child and maternal mortality to “below zero”.

Nairobi County official Oloo says that better communication for immunisation is a goal across his area, with health providers in underserved communities now being provided with a sustainable support group of 100,000 digitised community health promoters (CHPs) across the country. CHPs are currently being integrated within the Ministry of Health, through the primary health units domiciled in the communities they serve.

It is expected that CHPs will now more efficiently and effectively build bridges between health facilities and the community, to ensure that every health service delivery barrier is broken.