Inside the storm: How soaring hepatitis A rates are affecting Kerala

The southern Indian state of Kerala has witnessed a record surge in hepatitis A cases. Nasir Yousufi finds out what’s driving the viral spike.

- 12 July 2024

- 6 min read

- by Nasir Yousufi

As the group of drivers were about to finish their midday meal under a thatch shade by a taxi stand in Ernakulam on a scorching day, one of them started vomiting. He broke out in severe sweating, and complained of a headache. As his condition deteriorated, he was taken to nearby health centre. By the time his primary test results were out in the evening, he had been shifted to the city’s main public hospital.

Sreekanth, a 38-year-old driver from Vengoor village in Ernakulam, was confirmed to be infected with Hepatitis A, and like many other victims of the viral illness, he would be released from hospital cured in just a little over a week.

“[In the] past few years, like many parts of the country, the state has witnessed increase in temperatures and change in rainfall patterns. As a result, scarcity of clean water and floods lead to the increase in the number of cases of viral disease infections.”

- Dr E Sreekumar, Director of Institute of Advanced Virology, Kerala

Hepatitis A is an inflammation of the liver caused by the hepatitis A virus. Patients typically suffer fever, loss of appetite, diarrhoea, nausea, abdominal discomfort and dark-coloured urine. Unsafe food or water, inadequate sanitation, poor personal hygiene and physical contact are the main ways the disease spreads.

Unlike hepatitis B and C, hepatitis A doesn’t cause chronic liver disease, and is far less fatal, but symptoms can be debilitating. On rare occasions, the virus causes deadly acute liver failure, and the World Health Organization has reported an estimated 7,134 deaths from hepatitis A worldwide in a single year.

Rising caseload

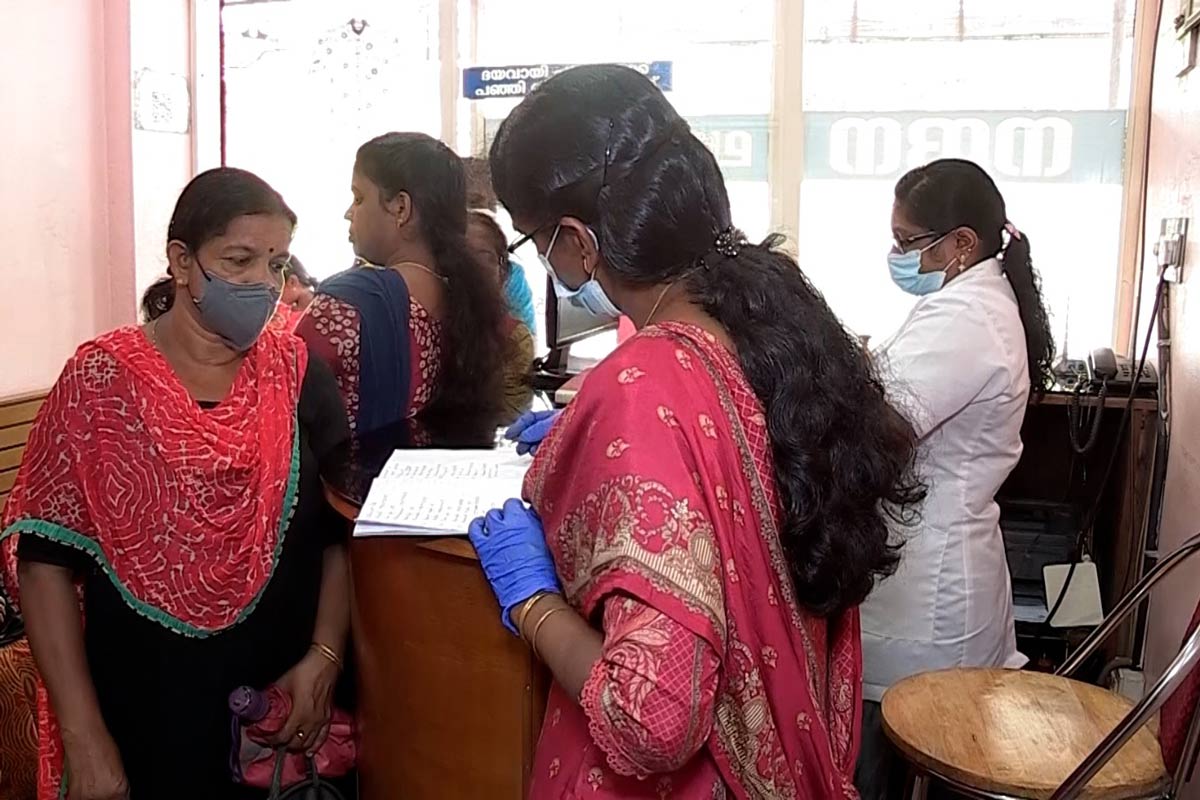

Recently, the southern Indian state of Kerala has been in the grip of a severe hepatitis A outbreak. Speaking to the media, Veena George, State Health Minister, sounded the alert on the outbreak in Kerala’s four most-affected districts: Ernakulam, Malapuram, Thrisur and Kozikhode. The number of cases statewide are suspected to have surpassed 6,000 in the first half of 2024 – a huge jump from the 2023 total of 1,073 confirmed cases.

But even 2023’s tally represented a sharp increase. As per the data provided by Directorate of Kerala Health Services, in 2022, Kerala recorded 231 cases, up from 134 cases recorded in 2021.

Vengoor Panchayat in Ernakulam district has been the village hit hardest. With a population of about 5,000 people, Vengoor recorded 271 confirmed cases. Officials at the local community health centre say it is now largely contained, with just three cases remaining in treatment at the time of writing.

According to Dr Harikumar S, Assistant Director, Kerala Health Services, his department has been quick to deal with the emerging situation.

A house-to-house fever survey, rapid diagnosis contact tracing, proper follow-up, awareness campaigns and cleanliness drives in affected areas have been promptly instituted to contain the outbreak, he said.

Bad water to blame

In Vengoor, a contaminated water source has been found to be the primary cause of the recent outbreak.

“We received a first confirmed case of hepatitis A on April 17. Acting swiftly, we at once conducted a fever survey in the whole village, and within a few days we were able to find many new cases in the village. Simultaneously, our teams searched for the possible source of viral infection in the village. After six days of thorough investigation, we were able to locate the water storage tanks supplying drinking water to the villagers as a primary source of infection,” said Dr Victor Joseph, medical superintendent of the Community Health Centre, Vengoor.

In Vengoor, it is believed that the water was contaminated by a leakage in the pipes, resulting in mixing of drinking water with unclean or untreated groundwater. But generally, the risk of contamination rises when water is scarce during the hotter months.

“The water storage tanks supplying water to villagers are maintained by Kerala Water Authority. Usually, we ensure that the chlorinated and safe drinking water is supplied in the village. But the authority sometimes supplies untreated water during the peak demand for water in summer,” said Silpa Sudheesh, president of the Vengoor panchayat (village council). In desperation, many villagers often also use contaminated ground water sources, leading to exposure to pathogens, including hepatitis A.

“A large number of people eat food outside home from eateries and restaurants or order outside food. Some of these eateries use untreated or contaminated water due to scarcity of clean water, particularly during summers, resulting in the spread of viral disease among the masses,” said Dr Ismail Siyad, a gastroenterologist at Aster Medcity hospital in Ernakulam.

Have you read?

Climate risk

Experts also attribute the surge in case numbers to climate change.

“[In the] past few years, like many parts of the country, the state has witnessed increase in temperatures and change in rainfall patterns. As a result, scarcity of clean water and floods lead to the increase in the number of cases of viral disease infections,” said Dr E Sreekumar, Director of Institute of Advanced Virology, Kerala.

The health officials said that people with co-morbidities are at higher risk from the disease.

Dr Siyad explained that the people most at risk of contracting hepatitis A include people living in slum areas with poor sanitation, homeless people, people with drug addictions, people living with HIV, and those who have physical contact with patients. Frequent intrastate and international travellers are also at higher risk of infection with the hepatitis A virus, he added.

Prevention

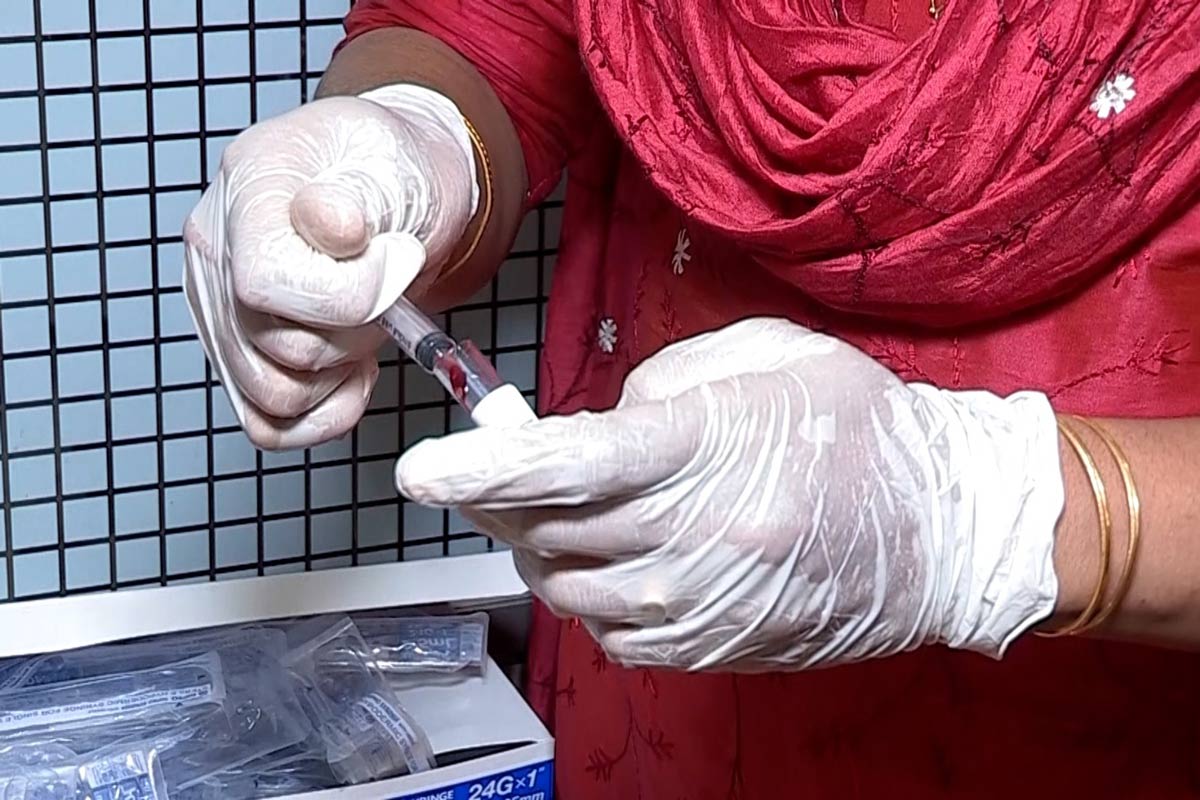

Besides adherence to good hygiene practices, chlorinating water and consuming safe food, health experts emphasise the importance of proper vaccination against hepatitis A and B to control the diseases.

Dr Prabhakaran, a senior gastro physician at Malabar Hospital in Kozhikhode, explained that in addition to routine vaccination of children above 12 months for hepatitis B – provided by the Indian state free of charge – people with resources to opt for private vaccination should get immunised for hepatitis A, he said.

The hepatitis A vaccine is presently a costly affair for the ordinary person. It is priced more than 600 rupees (about US$ 7.18) at most of the private health care facilities, said Dr Victor Joseph.

As parts of state grapple with the outbreak of the hepatitis A, the health system is under abnormal stress.

“I am overburdened. From last two months, I have not been able to take any leave due to workload of patients. Due to outbreak, I have to spend extra time in the hospital attending to the patients,” said Mohan, a paramedic in Ernakulam.

And while hepatitis A, unlike its cousins hepatitis B and C, is rarely fatal a serious bout of the illness can have significant economic ramifications. Sreekanth, the driver from Vegnoor, said he could not go to work for almost one and a half months after being hospitalised with the disease during the first week of May. He has had to borrow money from a friend to pay for grocery and power bills, he added.