Charting the unprotected: an illustrated guide to the zero-dose child

Too many children still aren’t receiving any routine immunisations. But who are they and where do they live?

- 6 December 2024

- 3 min read

- by Linda Geddes

Globally, around 14.5 million children didn’t receive any routine vaccines in 2023, putting them at risk of death and disability from infectious disease.

Although zero-dose children are found in many places, they often have certain things in common that mean they are less likely to be able to access vaccination. Understanding these barriers is key to designing innovative strategies to reach them.

Unvaccinated children often come from families that struggle to access other health services including medical care during pregnancy and childbirth.

Here are eight things we know about the average zero-dose child today.

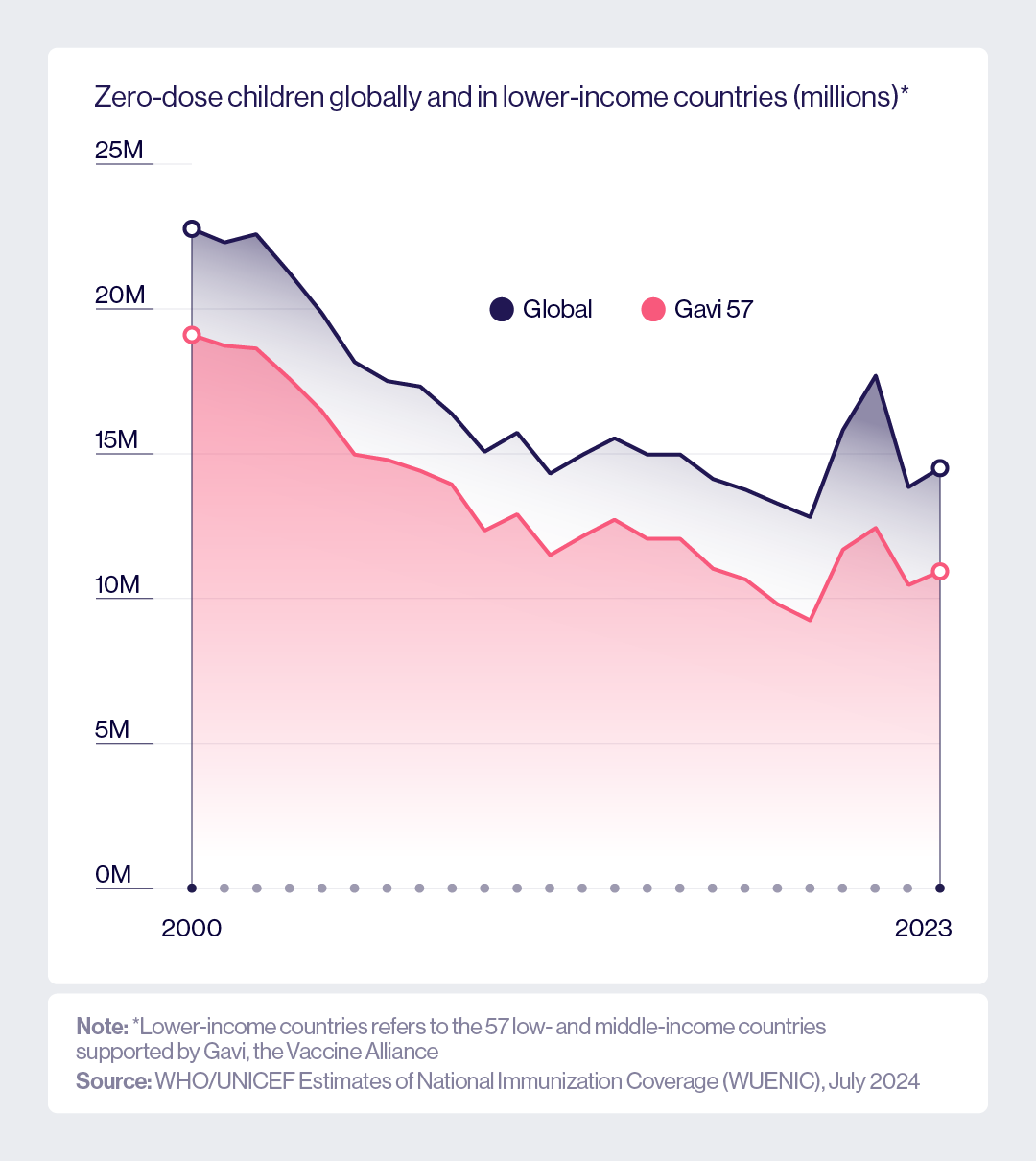

1. The number of zero-dose children has largely plateaued

Gavi defines a zero-dose child as one who hasn’t received any doses of the diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis-containing (DTP) vaccine – a proxy for immunisation coverage more broadly. Although the proportion of children who receive basic protection against these three diseases has significantly increased since 2000, progress has stalled in recent years.

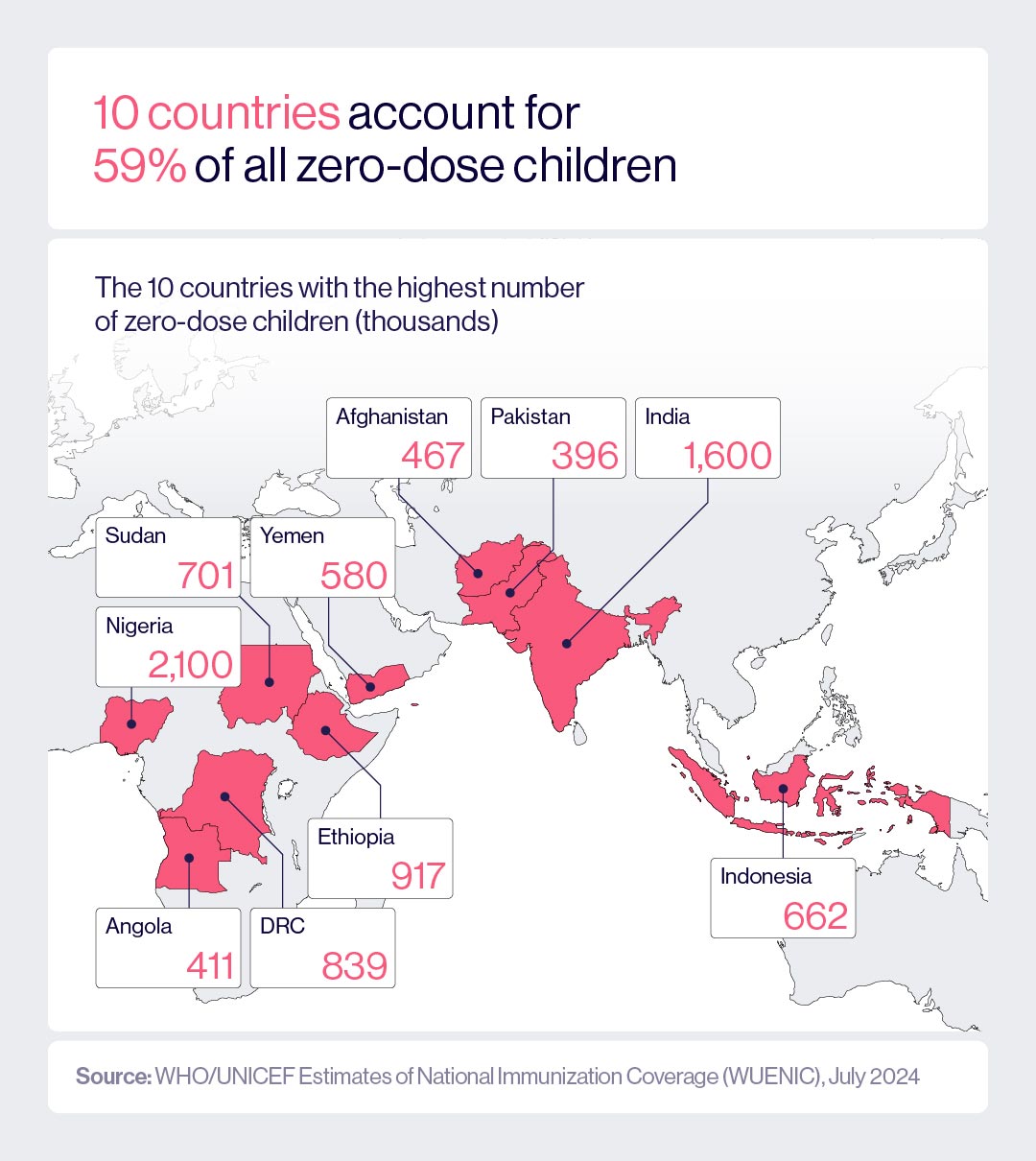

2. Three fifths of these children live in just ten countries

Although zero-dose children can be found in any country, most of them live in lower-income countries – particularly those with large birth cohorts, weak health systems, or both.

However, there are also some smaller countries that have even lower vaccination coverage, such as Papua New Guinea (45%), Somalia (52%) and Central African Republic (54%).

3. Living in a fragile or conflict-affected country greatly reduces a child’s likelihood of being vaccinated

Zero-dose children are disproportionally found in fragile or conflict-affected countries and territories, even though these places only account for 28% of the global birth cohort. Conflict often disrupts essential infrastructure and resources needed to deliver vaccines.

According to data from Save the Children, the number of children who have had no routine vaccinations is three times higher in conflict zones compared to the rest of the world.

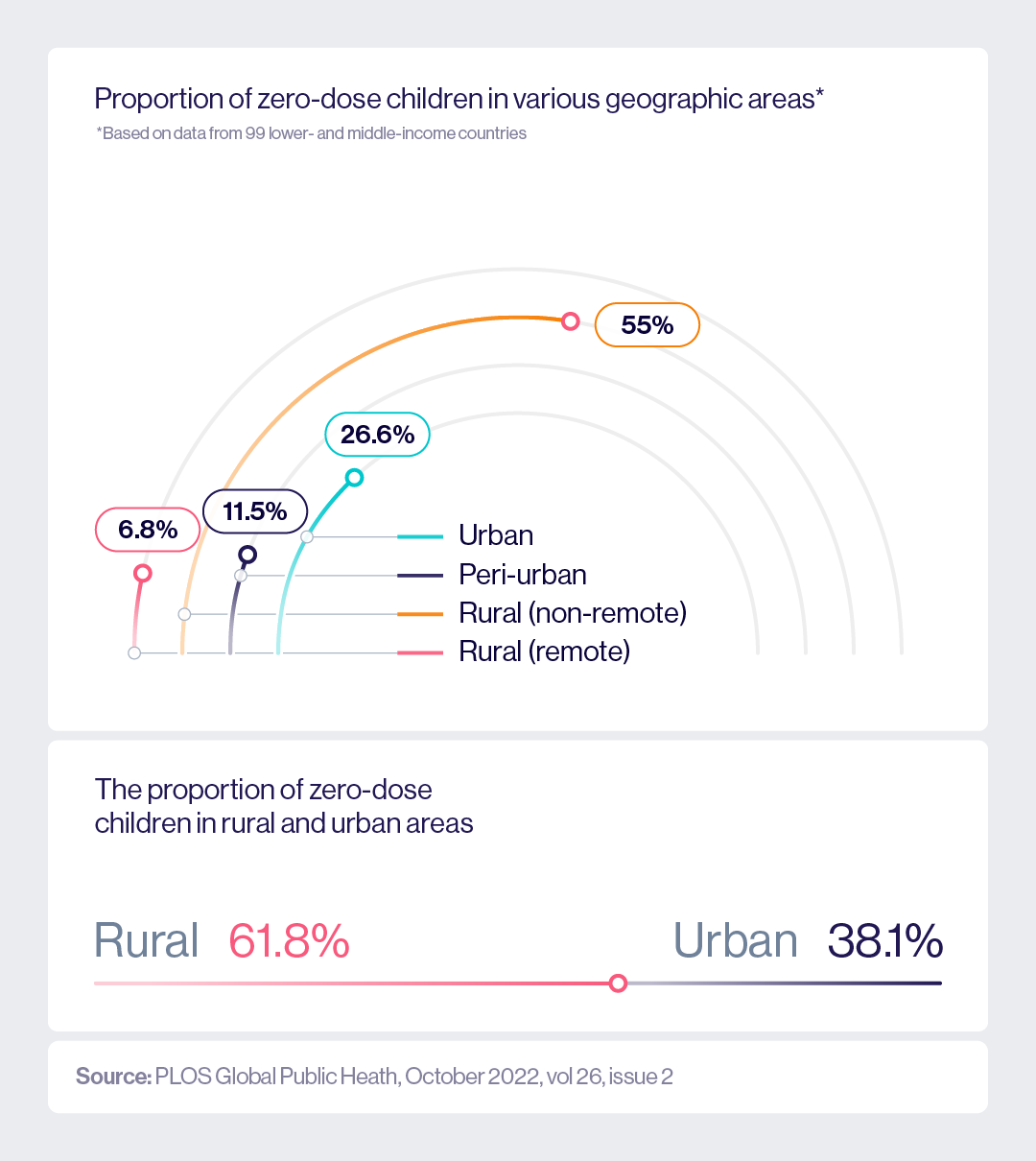

4. Children living in rural areas are less likely to have access to vaccines than their urban peers

A child’s chances of being unvaccinated also varies according to where in a country they live, with those living in remote rural communities, or impoverished urban slums, the most challenging to reach.

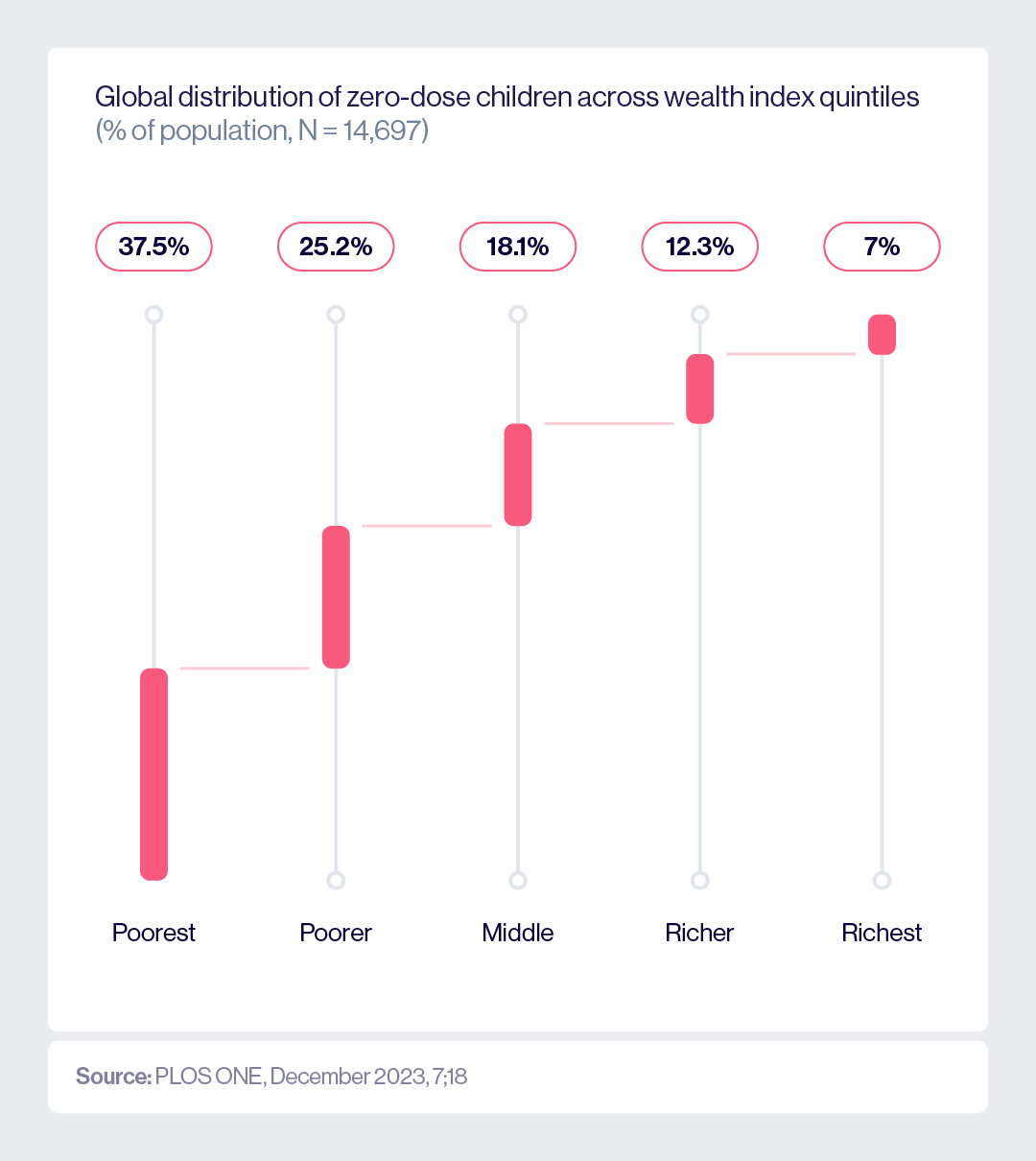

5. Zero-dose children are more likely to come from poor households

Children from poorer households are more likely to be unvaccinated than those from wealthier ones, with roughly two thirds of zero-dose children living in households with incomes below the international poverty line of US$ 1.90 per day.

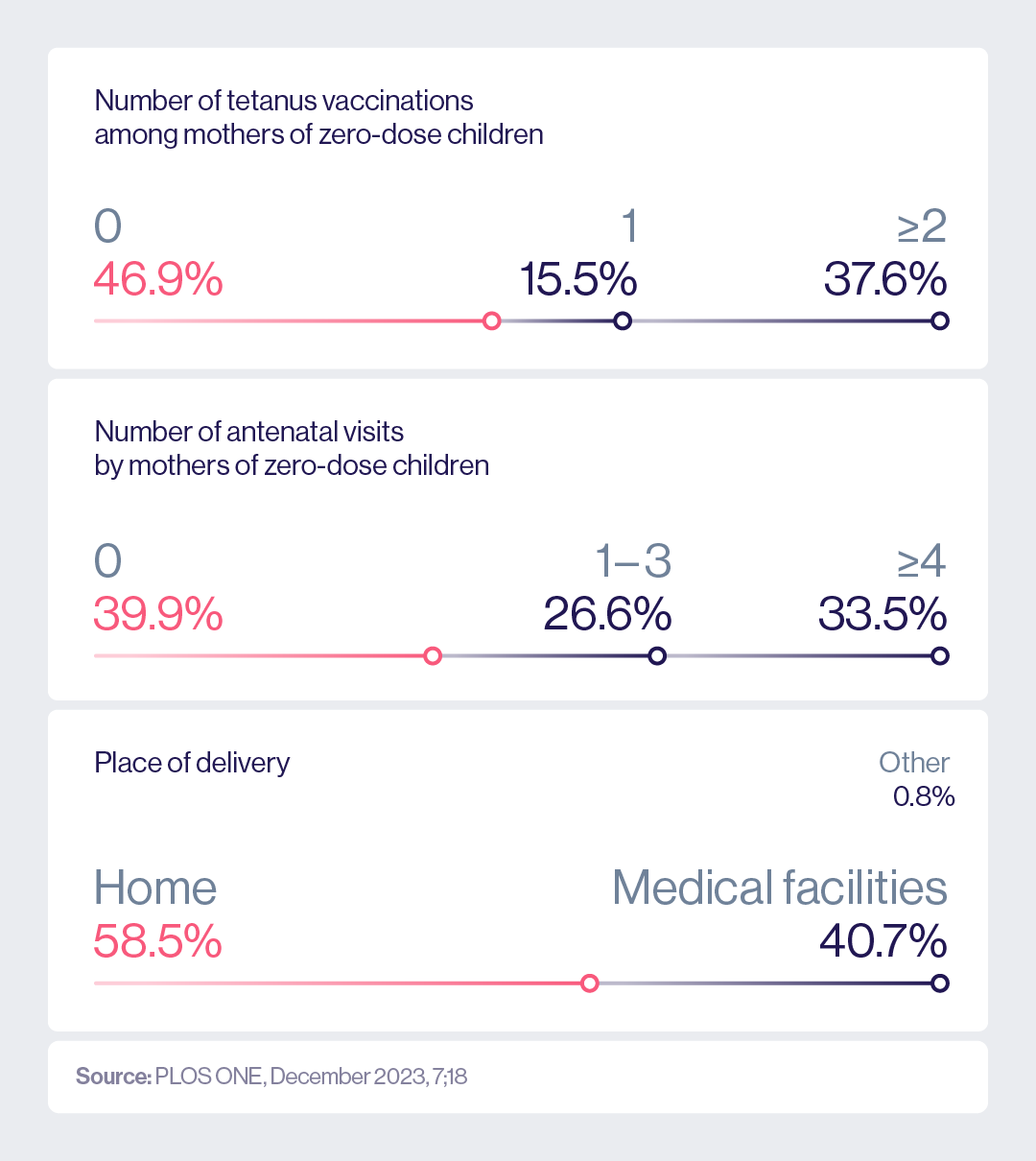

6. Their families may lack access to other types of health care

Unvaccinated children often come from families that struggle to access other health services including medical care during pregnancy and childbirth. Their parents may also have had limited access to vaccination. This is why strengthening the health systems that deliver vaccines is so important: it provides opportunities to boost access to health care more broadly.

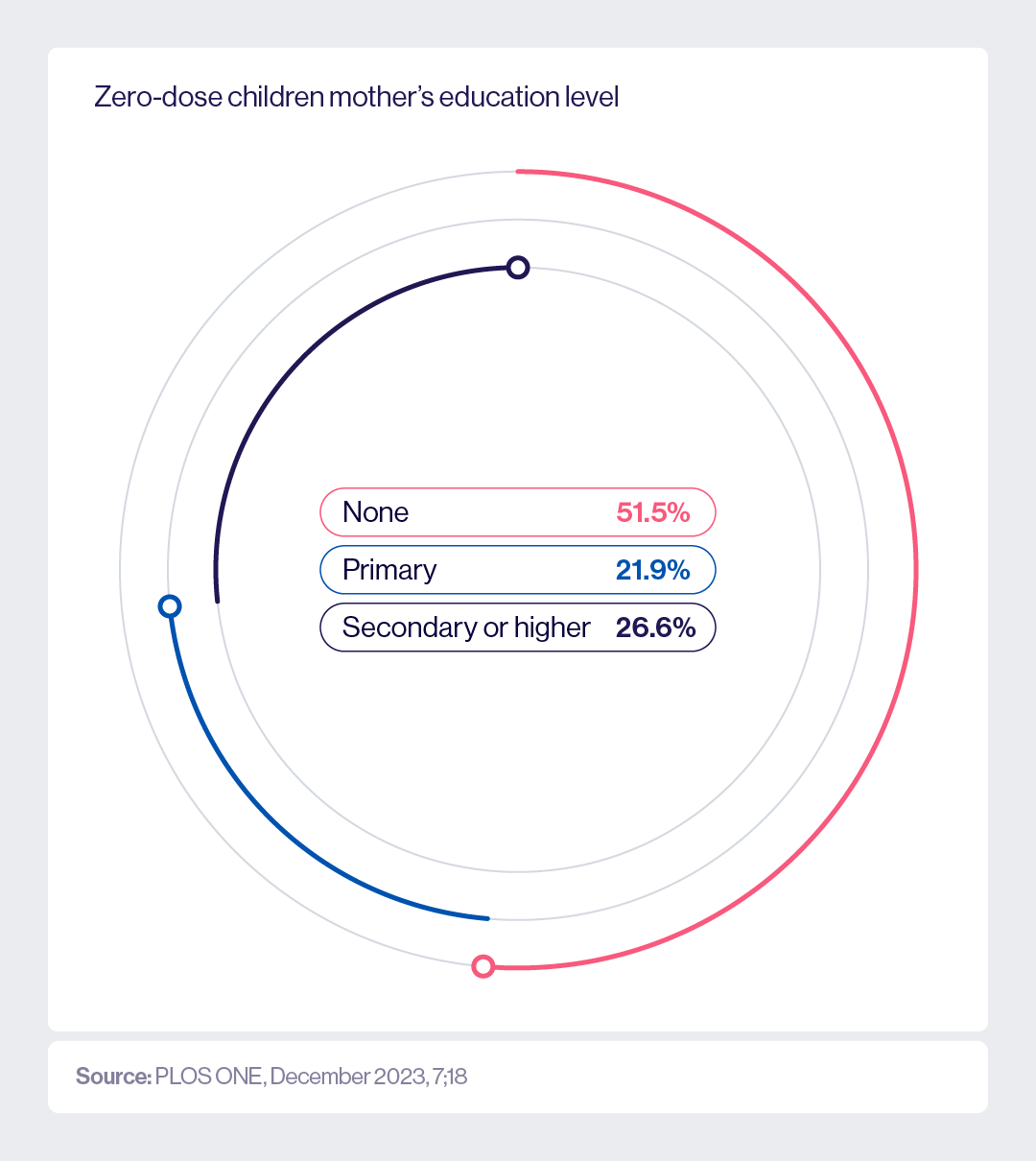

7. Zero-dose children are more likely to have mothers who didn’t complete their education

Although the relationship between vaccination and maternal education is complex, numerous studies have suggested that zero-dose children often have mothers who have not received education or only completed primary education. One reason may be that better educated people find it easier to access information about health. This emphasises the importance of making information about vaccines accessible to all.

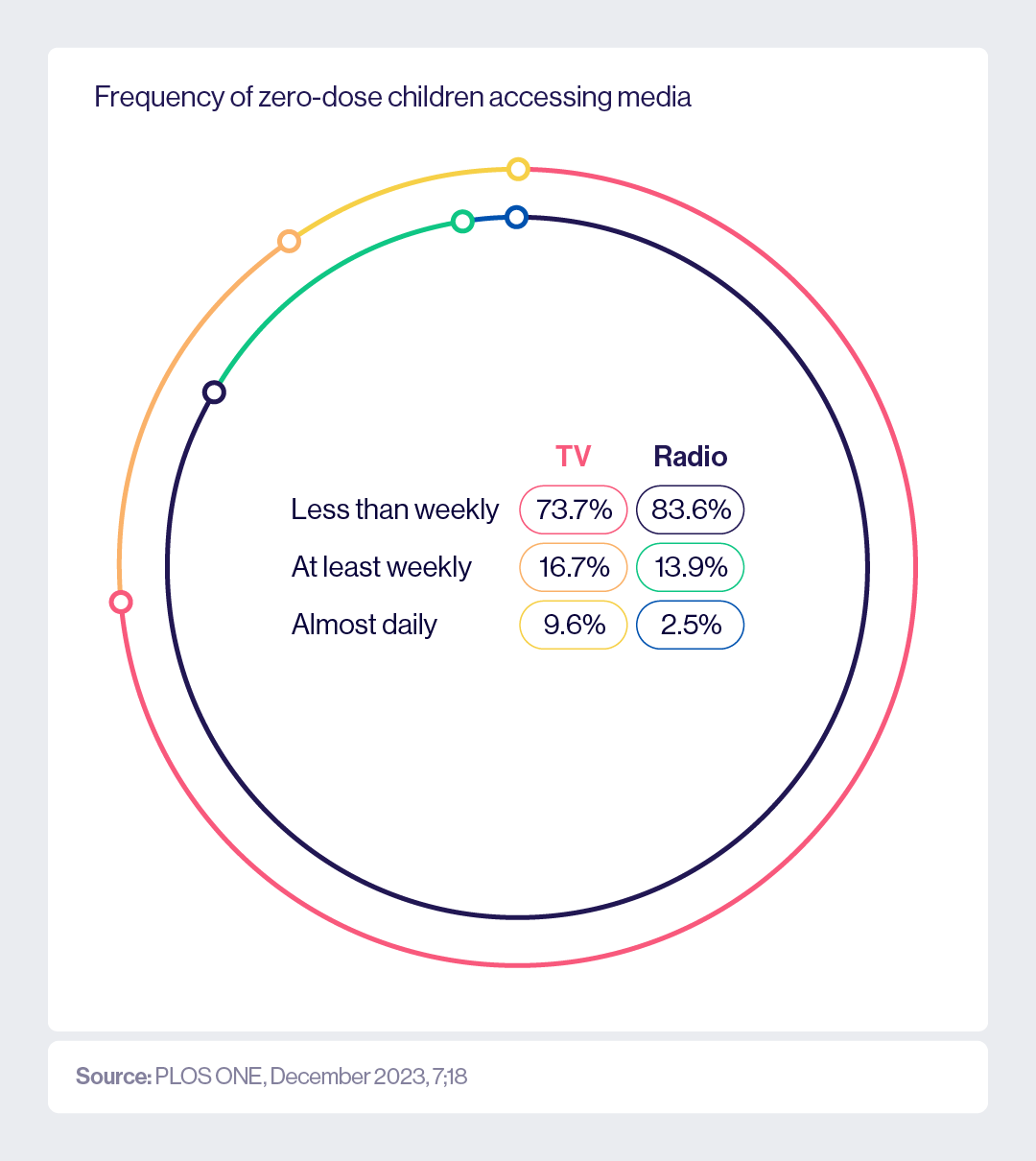

8. Most zero-dose children live in households with limited access to TV or radio

Particularly in low-income countries, the majority of unvaccinated children have mothers who watch TV less than once a week. This means they may have less access to national public health messaging and may be more influenced by what they hear from other people in their communities about the value of vaccination.