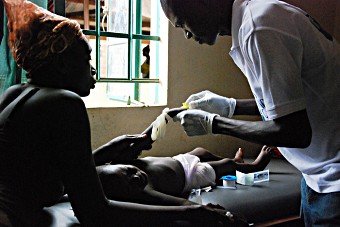

Abdul is hooked up to an IV line that will deliver life-saving fluids. Rehydration, administered orally, or, in severe cases like this, intravenously, can quickly revive a child, but not all children are lucky enough to live within reach of such help. Source: Doune Porter/GAVI/2011.

Sierra Leone, 7 June 2011- Two and a half year-old Abdul lay inert on his mother's lap when we arrived at the Gondama Community Health Centre, a tiny rural clinic in southern Sierra Leone. Abdul's mother, Aisha Kamara, had just brought him in and, tearful and terrified for her son, she talked to us while clinic staff readied for his treatment.

"He's been sick for four days," she told us, "He had diarrhoea and he kept getting weaker. He lost his appetite and stopped playing. Whatever he ate, he threw up. I just didn't know what to do."

Survival

Aisha earns a meagre living taking in washing for neighbours when she can get the work. She has been alone since her husband left her when she was two months pregnant.

"He is my only child," she cried.

Sierra Leone is one of the poorest countries in the world, its economic difficulties compounded by a five year war that ended in 2002. Although the country is making clear strides in its recovery from the war and progress in development, poverty is high and health care and education are at basic levels.

These factors come together with deadly results for young children. For every thousand children born there, 140 do not survive to their fifth birthday; diseases such as diarrhoea, pneumonia, and malaria, often combined with malnutrition, take the heaviest toll. Diarrhoea and pneumonia alone account for more than 40 per cent of the deaths of children under five.

Most of the diseases that kill young children are preventable or treatable or both.

Health education

With limited education, mothers frequently do not know the best ways to feed their children, or understand the importance of breastfeeding during the first six months of life; they do not know how good hygiene can make a difference to health, or, when their children get sick, when to seek professional medical help.

Fortunately, despite her uncertainty about what to do, Aisha had made the right decision in bringing Abdul to the clinic; and she lived close enough to get him there on time. Hooked up to an intravenous drip, the boy was quickly rehydrated and within an hour was sitting up and asking for food.

Mohamed Tarawally, the Community Health Officer at the health centre who saved Abdul's life, was happy about his patient, but stressed the importance of preventing such illness where possible.

After intravenous rehydration, Abdul is soon asking for food and waves while his delighted mother looks on. Vaccination against rotavirus could protect children from the leading cause of severe infant diarrhoea.

Source: Doune Porter/GAVI/2011

"Diarrhoea cases here are a common, common condition, everyday," he said. "Sometimes, before the parents get here, the child dies on the way."

Rotavirus vaccine support

Sierra Leone applied to the GAVI Alliance for a vaccine that will protect children against the leading cause of severe infant diarrhoea - rotavirus. Rotavirus is most dangerous in countries where access to basic healthcare is limited.

"Abdul is one of the lucky children, he is now recovering from diarrhoea," says Mohamed, "but unfortunately, not all children recover. The rotavirus vaccine would be perfect if it is introduced in our country."

At a pledging conference in London on June 13, international donors will be asked to pledge the US$ 3.7 billion needed to introduce rotavirus vaccines and vaccines against pneumococcal disease (the leading cause of pneumonia) in 40 of the world's poorest countries, including Sierra Leone, by 2015.

That would be a relief for mothers like Aisha and babies like Abdul.