Why a second dengue infection can be deadlier than the first

Our bodies produce antibodies to the virus after an initial infection, so why can reinfection be so much more serious?

- 30 January 2024

- 3 min read

- by Priya Joi

Dengue is surging in countries like India and Bangladesh, with the latter seeing more cases of the mosquito-borne disease than ever before. In Bangladesh's capital Dhaka, health care facilities have been so overwhelmed with dengue patients that COVID-19 hospitals have been converted to dengue wards.

Complicating the disease response is the fact that not only can people get infected with dengue multiple times since an initial infection doesn't confer long-lasting immunity as it does for some diseases, but also, a second infection of the virus can actually be far more deadly than the initial infection.

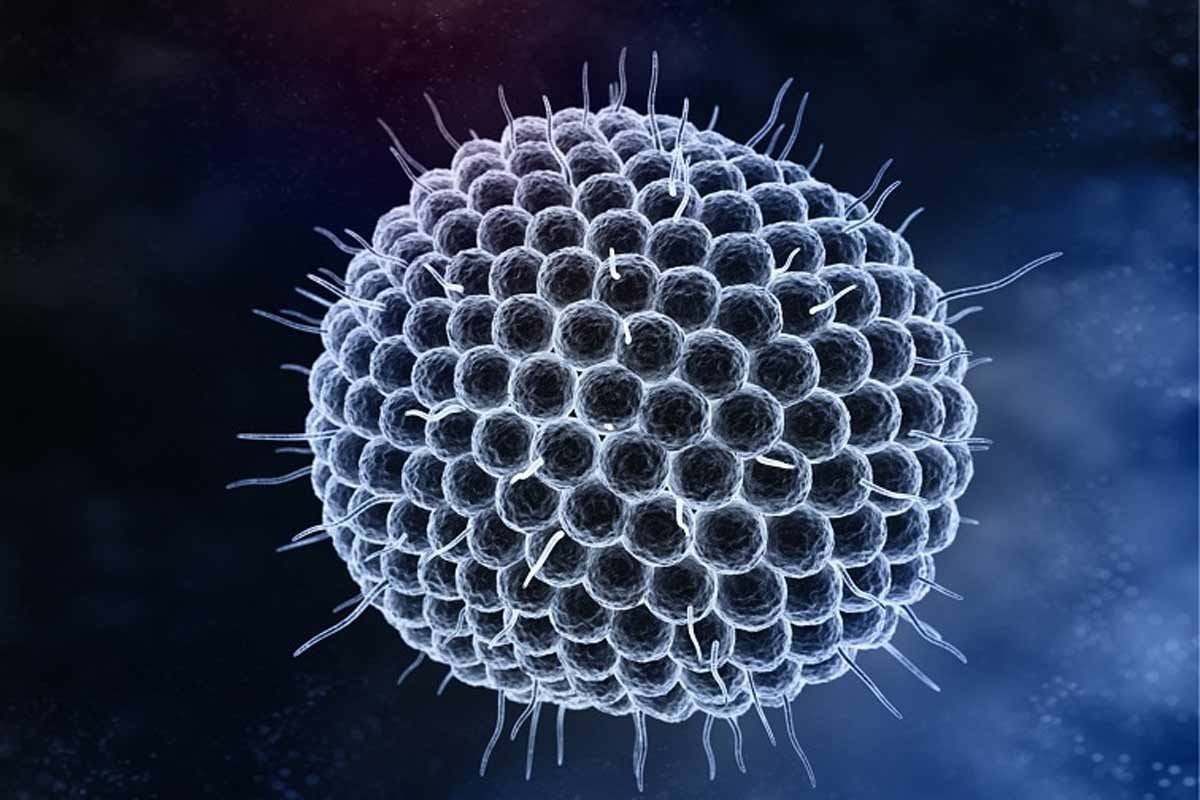

Subsequent reinfections with a different serotype can be so much worse, because of a process called antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). This is when pre-existing antibodies to one serotype bind to the virus particles from the new serotype that is infecting us, but fail to neutralise them.

In general, our immune systems are good at remembering when they have seen an infection before. Once we develop antibodies to a pathogen, memory immune cells mean that our body can quickly trigger them again when we encounter the pathogen a second time. Vaccines mimic this process by making our bodies think we've been infected, so that we can produce a surge of antibodies when we encounter an infection for real.

Have you read?

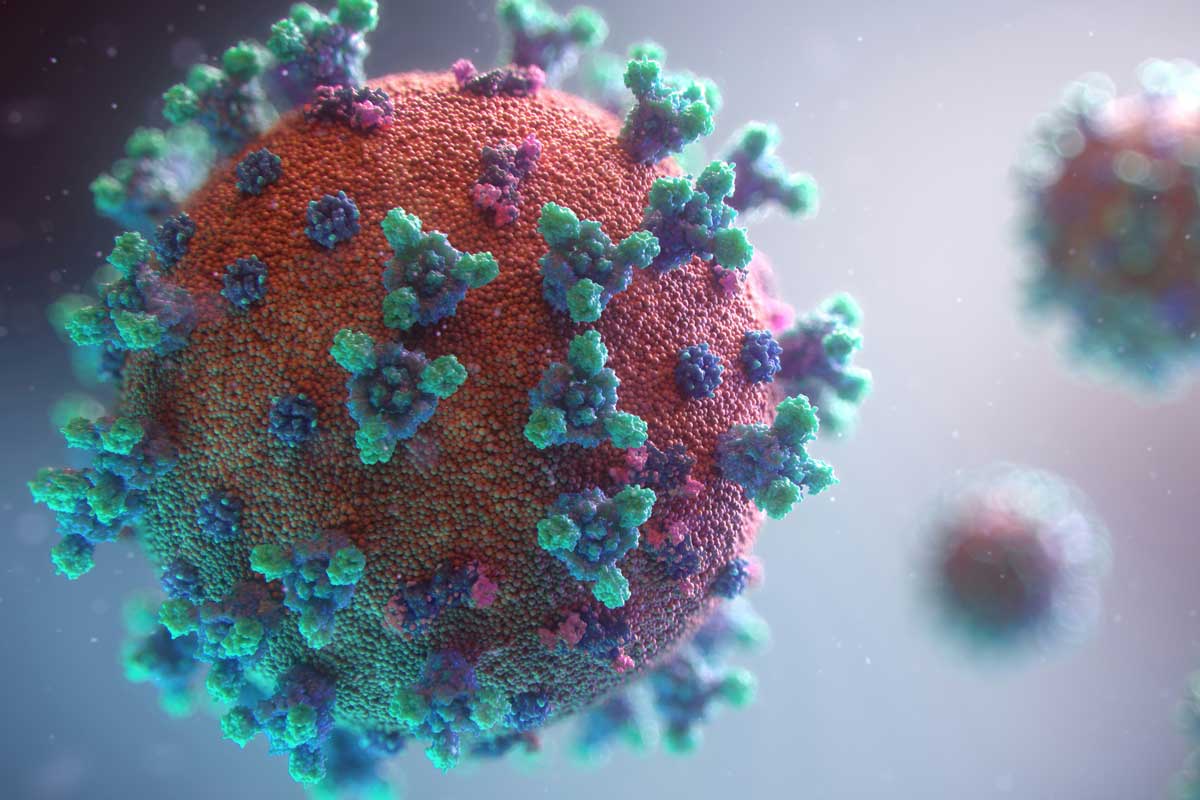

The dengue virus has four serotypes (denv1 to denv4) and we get infected by one of those serotypes at any one time. Although we develop lifelong immunity to that particular serotype, immunity to other three serotypes can be as short as two months, meaning the likelihood of a second infection – especially in a dengue outbreak – can be high.

And with dengue there's a twist – subsequent reinfections with a different serotype can be so much worse, because of a process called antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). This is when pre-existing antibodies to one serotype bind to the virus particles from the new serotype that is infecting us, but fail to neutralise them. Instead, this new virus-antibody complex is taken up by receptors that allow the virus to enter immune cells and replicate. This actually boosts the viral infection much higher than if the body didn't have pre-existing antibodies.

In response, this infection spike triggers a flood of immune cells called cytokines, in an extreme immune response called a 'cytokine storm' – this response was also responsible for the most severe symptoms in COVID-19.

What are cytokines?

Cytokines are small proteins that play an important role in controlling the growth and activity of other immune system cells and blood cells. When released, they signal the immune system to respond to a threat.

The cytokine storm can provoke such a strong response by the immune system that rather than protecting us from the infection, it backfires, causing us to haemorrhage and our organs to fail.