What does water mean to the world?

On 22 March 2021, the world marked World Water Day, with the theme for this year’s celebration being “valuing water.” What can the long history of water’s connection with health teach us about its true value to the world?

- 31 March 2021

- 4 min read

- by Tetsekela Anyiam-Osigwe

Throughout history, water has been closely tied to public health. Since antiquity, where marshy water was often avoided, it was already known that certain kinds of water were harmful to people’s health. By the 19th century the link between water and the transmission of several diseases, including typhoid, diarrhoea, dysentery and cholera, had been proven with the discovery of disease-causing microbes.

Credit: WHO/ Theo Janssen

In fact, modern epidemiology has its roots in the discovery of water's role in transmitting disease. John Snow was a mid-19th Century English physician who studied the pattern of disease to trace the source of a cholera outbreak in Soho, London, to a single water source. By ordering the handle on a communal water pump to be broken, he was able to end the outbreak, as well as the miasma theory of disease - the theory that 'bad air' is the reason diseases like cholera spread. Bad water was, in fact, the culprit.

The sewerage and sanitation systems that sprung up in cities across the world following this discovery quickly reduced the horrific toll of water-borne diseases. However they also helped turn one in particular into one of the world's most-feared diseases.

Poliomyelitis had existed for most of human history, however it had been a relatively unremarkable disease, mostly causing only mild illness in children. But in the early 1900s it suddenly became more rampant, killing thousands and causing paralysis in many more, particularly in wealthier areas. Better sanitation and clean water meant that people stopped encountering the disease as babies, when antibodies passed through the womb and their mothers' breast milk, giving them immunity. Encountering the disease at this early stage meant symptoms similar to a mild cold, and by fighting off the disease the babies would receive life-long immunity.

However when clean water and sanitation stopped babies from encountering the water-borne disease, this life-long immunity never developed. When they then contracted the disease later in life this meant that a far more severe form of the disease developed. Polio killed thousands of people worldwide every year until a vaccine was developed in the 1950s, providing the immunity that had been lost with the introduction of clean water and sanitation.

Have you read?

Our “blue gold” under pressure

Around the world there are many communities, that lack adequate access to water resources. Increasingly, water has come under pressure to meet the social, economic, environmental and health needs of an ever-growing global population. Billions of people still lack access to safely managed drinking water and sanitation services, with severe water scarcity expected to displace as many as 700 million people by 2030.

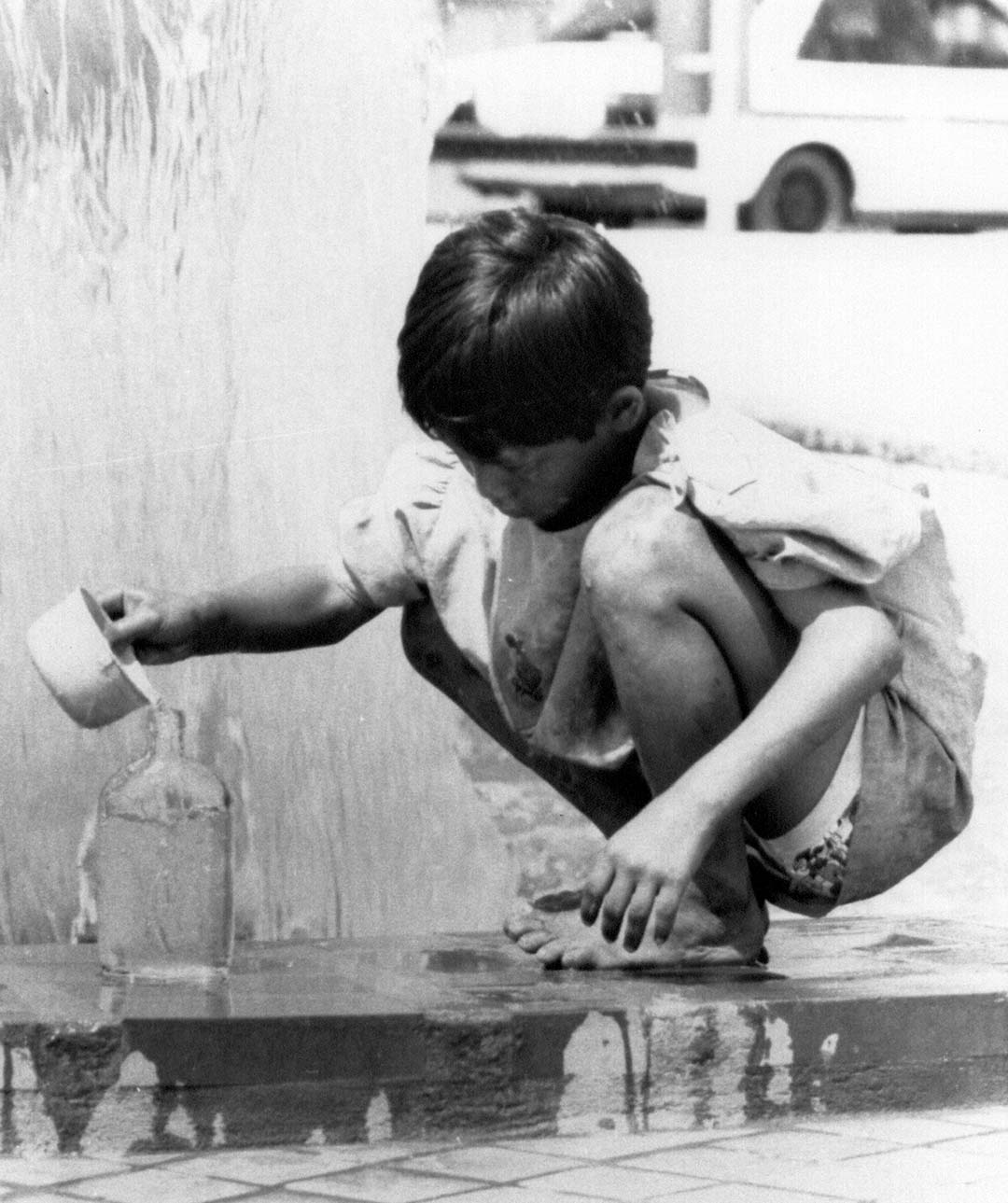

Credit: WHO/Diyawanga

This lack of access to water can lead to creative solutions. In the Canto Grande suburb outside Lima, thousands of migrants were forced together in cramped conditions with no clean water. People looked for ways to get access. Soon, they began to rely on tapping roving tankers passing through Canto Grande. Whilst not the most reliable source, it still ensured that some water was available to the community.

Credit: WHO/Didier Henrioud

Water and the fight against COVID-19

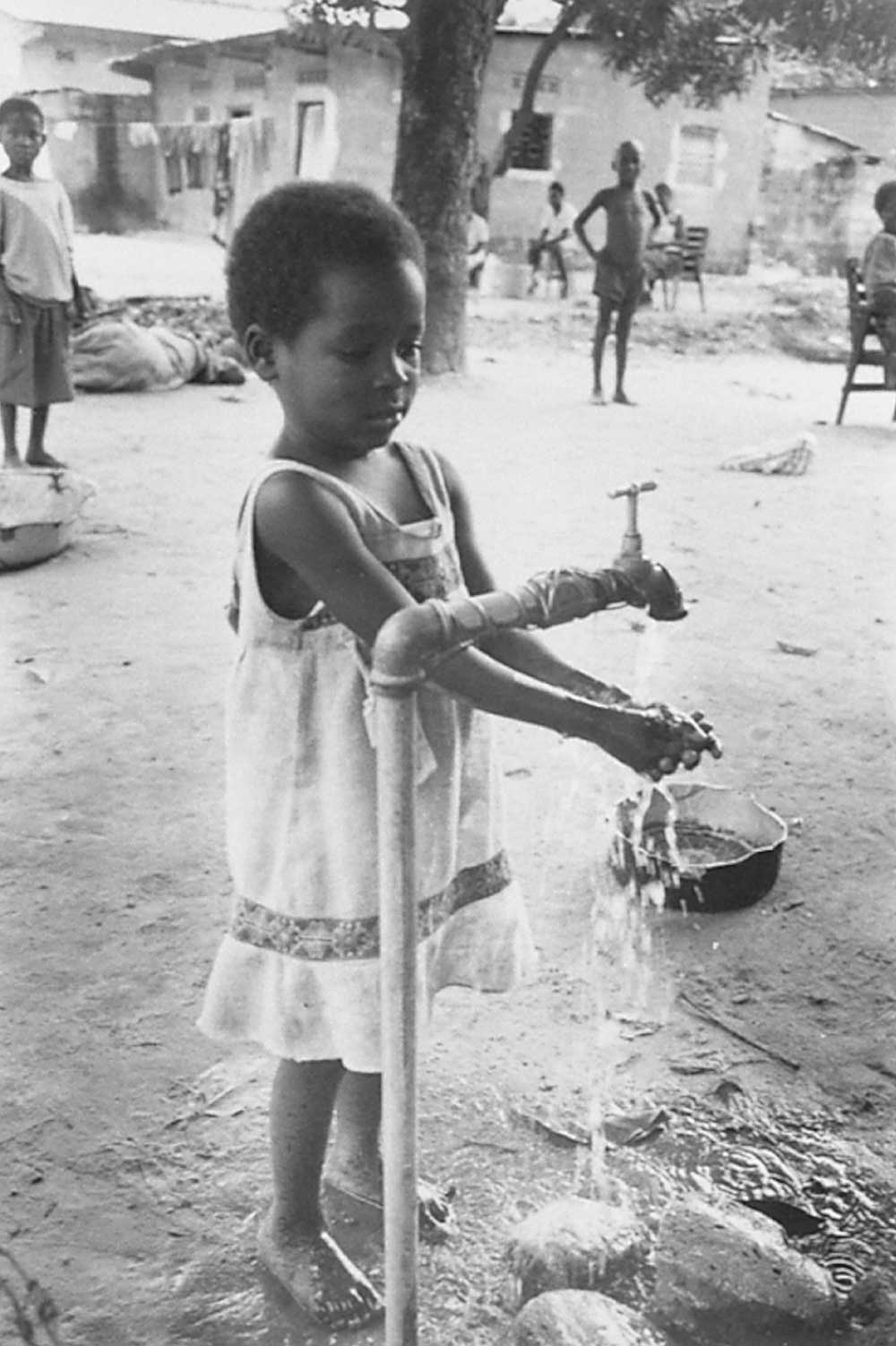

According to the United Nations, over three billion people and two out of five healthcare facilities lack adequate access to hand hygiene facilities. This is a major problem in the context of a global pandemic in which handwashing continues to be an essential first line of defence against both catching and transmitting COVID-19. Whilst frequent handwashing is a simple and straightforward daily routine for some, it is a luxury for many people living in communities that face the difficult decision of whether to use the limited water available to them to wash their hands, drink or make food.

Credit: Gavi/2016/Kate Holt

With the UN now stressing the urgent need to recognise and express water’s worth, especially as we look towards ending a pandemic where, even with ongoing vaccinations, universal access to water for good hand hygiene still constitutes an invaluable weapon in the fight against COVID-19.

More from Tetsekela Anyiam-Osigwe

Recommended for you