Thank you, and sorry: vaccination’s bone-deep debt to the animal kingdom

It’s World Animal Day and we’re tipping our collective editorial hat to the animals who make, and have made, vaccination possible.

- 4 October 2024

- 5 min read

- by Maya Prabhu , James Fulker

At the beginning, of course, there was the generous cow: the vacca who gave us vaccinia, and thence, vaccination.

Edward Jenner may have been the first to systematise the evidence and outline a process, but he wasn’t the first to suspect that infection with the minor nuisance, cowpox, offered a shield against deadly smallpox. That pattern was already talked about among dairymen and women.

In 1768, 30 years before Jenner undertook his vaccination project, a Gloucestershire farmer proved unresponsive to variolation, a forerunner procedure that used small quantities of the lethal smallpox virus in a fairly risky effort to produce immunity without exciting full-scale infection. By way of explanation, the farmer told the surprised inoculating surgeon: “I have had the Cow Pox lately to a violent degree, if that’s any odds.”

By the mid-late 19th century, animals would be drafted into the vaccine production process too. Before refrigeration technology could help us keep the packaged stuff fresh, cowpox vaccine lymph destined for humans was farmed in sheep, cattle and water buffaloes.

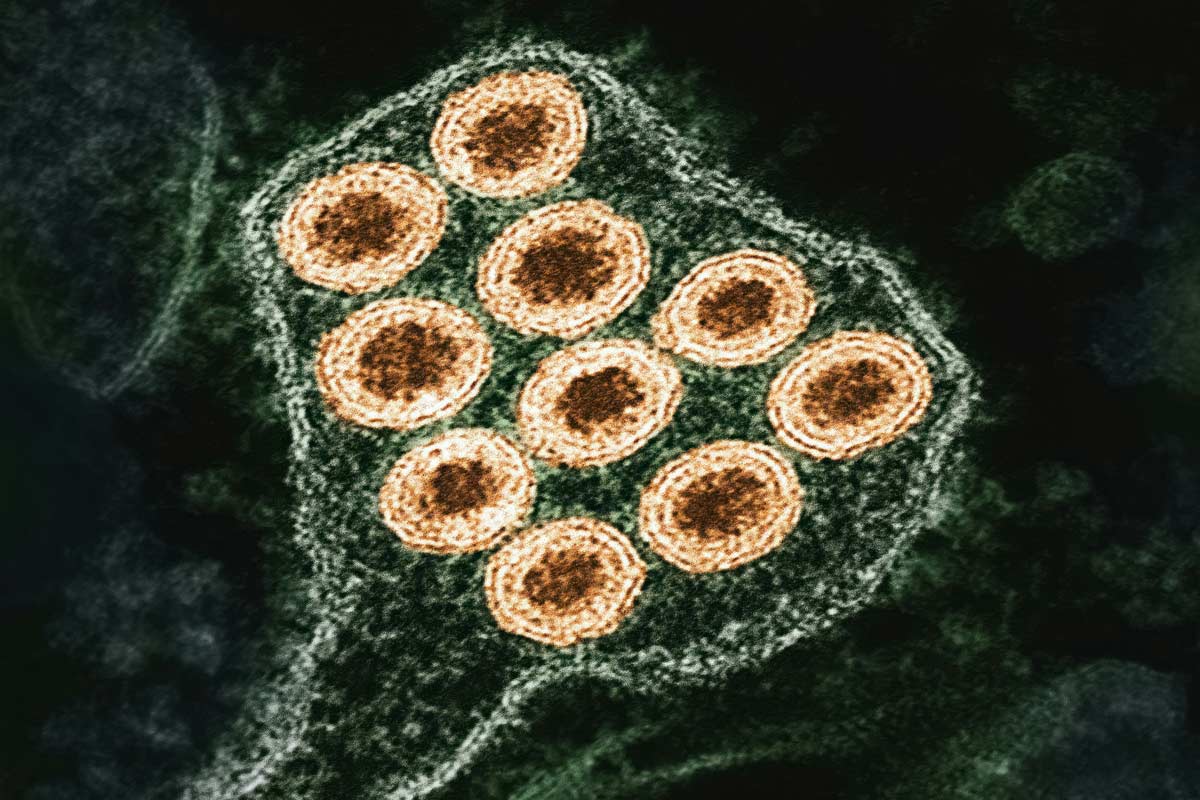

At that time, the science of vaccination was beginning to sprout new branches, splitting away from its bovine origin. It never moved far from its reliance on animals however – their immune systems, valuably both different and similar to ours, and, sadly, their convenient powerlessness.

In 1879, Louis Pasteur found, via mild neglect and good luck, a laboratory-based method for attenuating – that is, weakening – the germs (bacteria, in fact) which caused a poultry disease called chicken cholera, creating, in that process the the second “vaccine”. With his new method, Pasteur locked sights on the third: for anthrax, a disease of animals capable of killing humans too.

But in the pursuit of a vaccine for rabies, Pasteur would need to find a very different attenuation process. This was dependent, at every stage, on laboratory animals.

Unlike anthrax, rabies is a virus, and proved evasive to culture in vitro. As such, Pasteur could only work on building his attenuated vaccine strain inside the bodies of animals. He began with infected dogs, and figured out how to passage the contagious material through long chains of rabbits, making a quicker version of the virus, before he set about weakening it to the point of safe use by desiccating the spinal matter of those infected creatures.

Skip ahead to the 1950s, and a similar concept – the repetitive passaging of virus through animal cells, here, fertile and fertilised chicken eggs – was in use in the hunt for the first measles vaccine. The underlying idea was a throwback to the story of vaccinia: if you could take a human pathogen, and encourage it to adapt to an animal host, could you then safely put it back in a human as an effective vaccine? The answer, with strings of asterisks and after years of adjustments, was, finally, yes.

The chicken eggs can excite only tepid sympathy from these non-vegan writers, but poor rabbits. Poor dogs, rodents, birds, primates and other unhappy creatures littering the history of medical ambition. The laboratory is a horrible place to live and die. Without calling it a necessary sacrifice – that sticks in the throat, there can be no doubt that the vast scale of animal suffering has been superfluous even to science’s stated ends – we acknowledge that, broadly, their loss is our collective gain.

There have been, however, many less miserable animals working on the side of vaccine delivery – creatures whose contribution has not required them to be killed or caged and forcibly infected with awful diseases.

At VaccinesWork we’ve encountered several who have carried vaccines and vaccinators into terrain that makes a fool of motorised vehicles, getting vaccines to children who would otherwise confront a lifetime of pathogenic onslaught without them. On World Animal Day, we invite you to revisit a few of our favourites.

- The Editors

Camels in the desert

Samburu, Kenya: When the pandemic put off the year’s important camel-races and blocked the inflow of tourism to Samburu county in Northern Kenya, John Lepankoi was one of several camel trainers who decided to link up with local health officials and make their idle animals available to the COVID-19 vaccination campaign. “Our joint campaigns have netted 300 camels for mobile COVID-19 vaccine efforts,” he told VaccinesWork back in 2021.

Tharparkar, Pakistan: COVID-19 had disrupted immunisation and measles was threatening a resurgence. In late 2021, Pakistan set out to immunise a staggering 90 million kids against the viral disease within just two weeks. In the desert of district Tharpakar, the quickest way to get MR doses from village to village was at the nodding pace of a riding camel.

Red Sea state, Sudan: In February this year, Abdul Qader from Red Sea state in Sudan – the country that is home to the world’s third-largest camel population – traded his motorbike for a camel on the way to remote Warhat village, where a group of nomadic Beja pastoralists were encamped. Without Qader and his ambling friend, six-month old Muhammad Saleh would have remained unimmunised.

Horses in the Himalayas

In mountainous Dolpa district, Nepal, VaccinesWork met nurse Pemba Gurung, astride her pony. The surefooted white gelding is often her only companion for days at a time – and the quickest means of transport available to the vaccinator.

Same mountain range, different country: paramedic Irshad Ahmad of Kupwara district, India, walks with a cane – a disability that doesn’t slow him down at all when he’s mounted on a horse loaned to him by a helpful neighbour.

Huskies in the snow

In 1925, a dramatic five-day dog-sled delivery of doses of vital antiserum – we concede, not exactly a vaccine – saved children struck by diphtheria in hard-to-reach Nome, Alaska. Just a few years later, vaccination could have saved the mushers the trouble.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you