Most of Islamabad’s slums now have an immunisation outpost, and that’s helping get more kids protected

Co-run by the public health system and the communities themselves, the immunisation centres bring prevention into reach for the city’s poorest.

- 31 March 2025

- 4 min read

- by Rahul Basharat

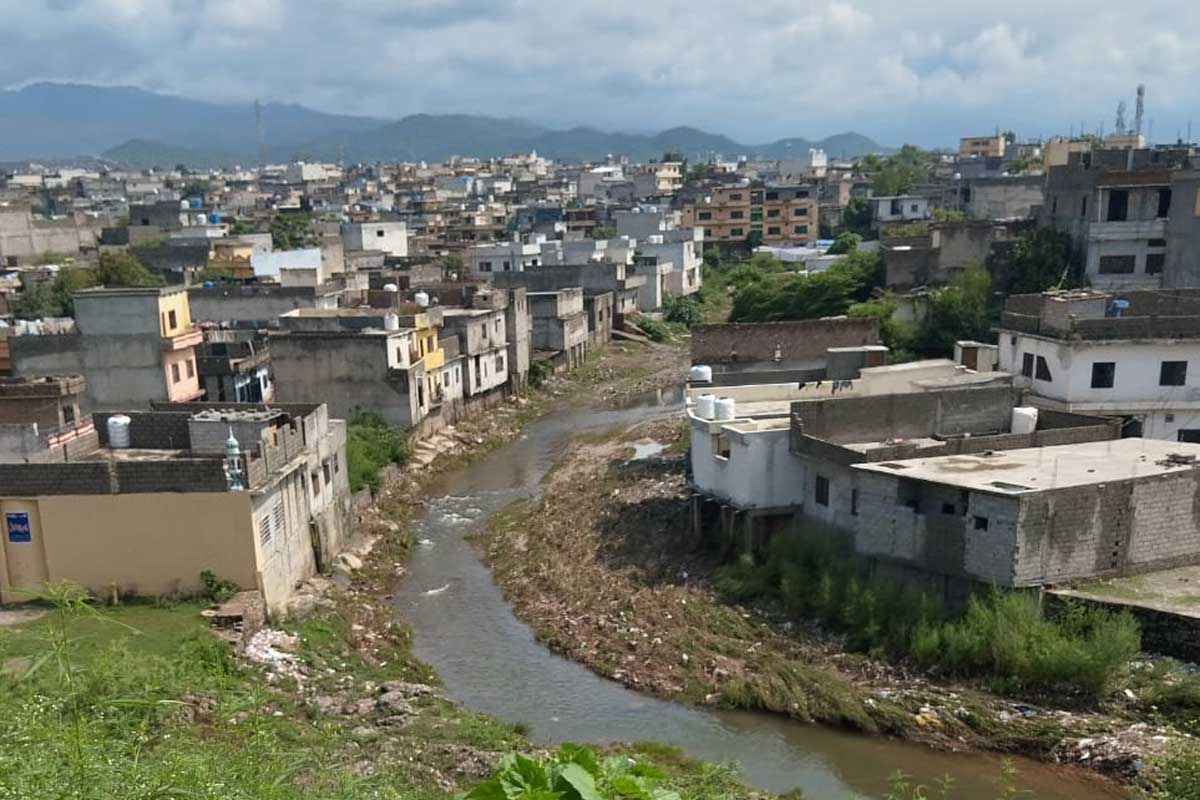

Islamabad’s F-7 sector is affluent: large residential bungalows line the streets, and commercial centres cater to well-to-do shoppers. But directly adjacent to this plush city quarter lies France Colony, a katchi abadi, or informal settlement, whose residents lack many basic necessities, including a clean living environment.

Most of the people of France Colony work in the city’s sanitation department, or take up small jobs in the homes and offices of their wealthy neighbours. One of them is Sunil David, a 24-year-old office boy, who also works with the health department as a part-time vaccinator.

Although the financial compensation for this work is small, David continues it out of a sense of service to his community. He explains that much like other informal settlements across Pakistan, France Colony lacks the educational facilities, health services and other public provisions extended to better-off locales – but in recent years, city’s health department has increased its focus on vaccinating its children.

“The simple and clear objective of this effort is to ensure that children under the age of five in slums receive routine immunisations, protecting them from multiple vaccine preventable diseases,” says David.

Catch-up at the katchi abadi

Over the past two decades, the number of informal settlements in Islamabad has increased significantly, rising from 12 to 60. According to a UNICEF report, by 2020 the cumulative population of the city’s slums was approximately 400,000.

The same report found that 16% of children in these areas had not received a single dose of vaccines, while 33% had received only one dose.

To get more children protected from dangerous childhood illnesses, Islamabad’s district administration and the Expanded Programme on Immunization have established immunisation centres in the city’s katchi abadis, with the buy-in and assistance of local residents.

Shezan Daniel, a community leader and resident of an informal settlement in Islamabad, advocates for the rights of the people living there, and works with his local vaccination centre.

The set-up is simple. The community designates a specific location within the settlement, Shezan explains, such as a church, mosque or temple, and on a regularly scheduled weekday, health department personnel visit that spot to administer vaccines to children.

Then, in order to shore up trust within the community, the health department hires vaccinators and lady health workers (LHWs) from within the settlement. These workers not only assist in administering vaccines, but also help spread awareness among local residents about the importance of immunisation.

“Many people don’t take their children for vaccinations due to overcrowding in major hospitals, unawareness or other reasons. This programme brings the service directly to their doorstep, ensuring that their children get the necessary protection,” Shezan says, adding that about 40 out of 60 of the city’s slums now have a similar facility.

Dr Syeda Rashida Batool, District Health Officer (DHO) Islamabad, told VaccinesWork that recruiting social mobilisers LHWs from within the community has proven crucial. Encountering familiar faces “not only increases vaccination rates, but also fosters a positive attitude towards vaccination”, she explains.

“Additionally, an Integrated Service Delivery (ISD) initiative has been introduced, incorporating extended hours activities in the evening. This approach addresses a significant barrier to immunisation. Many mothers in these communities work during the day and are unable to bring their children for vaccination [during standard clinic hours],” said the DHO.

Have you read?

Averaging 90% coverage

Dr Batool says the current immunisation coverage rate in Islamabad’s slum areas varies across different Union Councils (UCs), reflecting the diverse challenges and healthcare access levels in these underserved communities. She said, however, these areas are systematically covered by both the Health Risk Management Program (HRMP) and routine vaccinators.

“Through the combined efforts of these dedicated teams, the average vaccination coverage rate in slum areas has reached an estimated 90%,” says Dr Batool.

Declaring it a significant achievement, she credits the improvement to continuous outreach, targeted interventions, and community engagement strategies designed to overcome barriers such as vaccine hesitancy, lack of awareness and logistical challenges.

However, she said despite the evident progress, ongoing efforts are required to further improve coverage rates, bridge remaining gaps and sustain high immunisation levels.

“Strengthening community-based initiatives, expanding outreach activities and addressing specific barriers unique to different Union Councils will be critical in achieving universal immunisation coverage and protecting vulnerable populations from preventable diseases,” said Dr Batool.