Malaria vaccines are finally ready for action: what happens next?

After more than 50 years of research, the RTS,S /AS01e vaccine is on the brink of being rolled out to countries with moderate to high transmission of the world’s deadliest malaria parasite. Here’s how that roll-out will proceed.

- 25 April 2023

- 5 min read

- by Linda Geddes

In October 2021, the WHO gave the green light to use theRTS,S /AS01emalaria vaccine to protect children in regions with moderate to high transmission of Plasmodium falciparum – the world's deadliest malaria parasite.

It was a historic breakthrough: for more than 50 years, scientists have been trying to develop a vaccine against this foe, but their task proved exceptionally tricky. The malaria parasite is a shapeshifter, taking on different forms during its lifecycle and changing the proteins on its surface to escape the immune system. Now, the world is on the brink of another historic moment: the roll-out of the world's first malaria vaccine to children in greatest need of protection from this global killer.

The RTS,S vaccine is safe and effective, and implementation has resulted in a substantial drop in hospitalisations and child deaths from malaria.

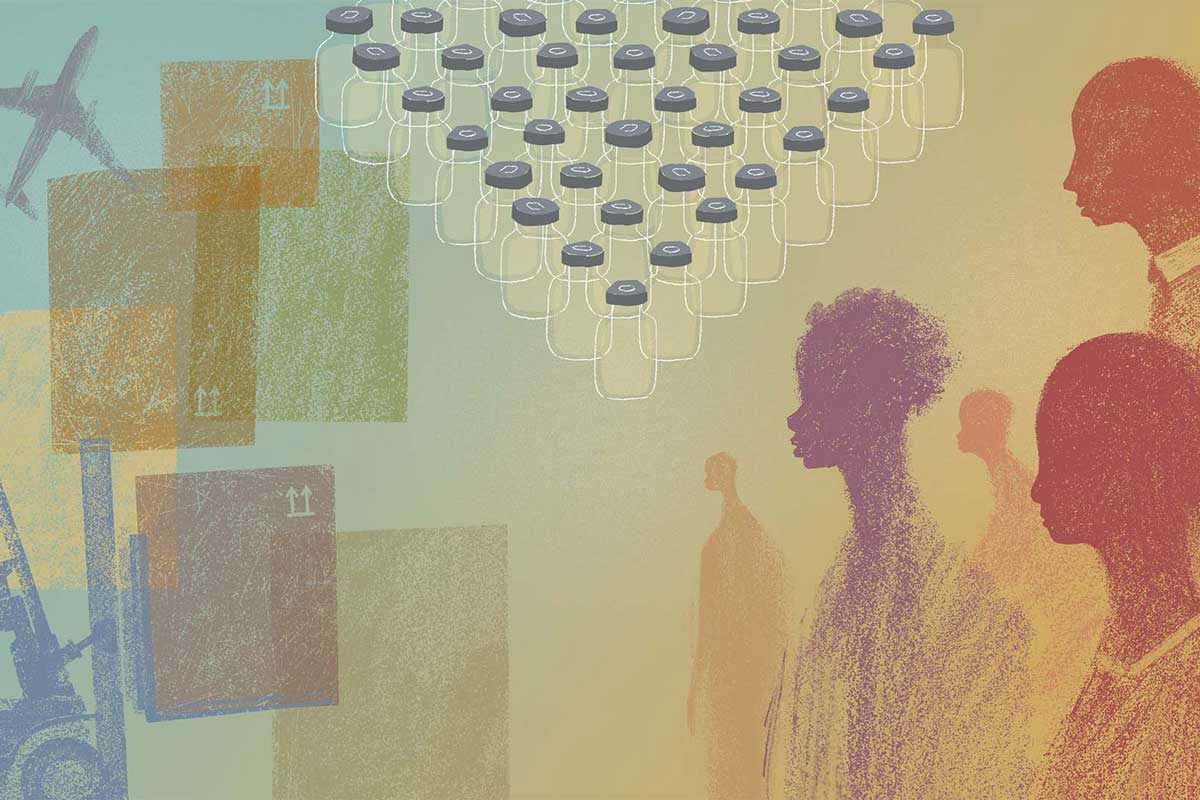

Pilot vaccination programmes launched in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi in 2019, have shown that the RTS,S vaccine is safe and effective, and implementation has resulted in a substantial drop in hospitalisations and child deaths from malaria. Indeed, assuming global RTS,S vaccine supplies reach 30 million doses, modelling has suggested that the deaths of some 24,000 children a year could be averted. It is hoped that other malaria vaccines currently in trials or at earlier phases of development will further increase the numbers of lives saved through roll-out of additional supply to meet demand.

Yet there are still some hurdles to overcome before every child at risk will have the opportunity to be vaccinated against it.

In October 2021, the Gavi board approved funding to support malaria vaccine roll-out in areas of moderate to high P. falciparum malaria transmission. The first countries to benefit from this funding are Ghana, Kenya and Malawi, where it is being used to support continued implementation of RTS,S/AS01e vaccination programmes.

The coming months

Non-pilot countries were invited to apply for Gavi support in January and April 2023, with the first allocations of vaccines expected to be announced shortly. However, because it will take time for the vaccine's manufacturer, GSK, to scale up production, doses are expected to be initially targeted at populations in areas of greatest need. As production is steadily increased, they will be made available more widely.

Have you read?

For these additional countries, phased introduction of malaria vaccination could begin as soon as late 2023 or – more likely – early 2024. Ahead of this date, countries will begin preparing for the vaccine's introduction by ensuring adequate supply of injection devices, making sure cold-chain provision is in place to support transportation and storage of the vaccine, training health workers on delivery of the vaccine, and informing caregivers and communities about the benefits and risks of vaccination and the importance of continuing other malaria control measures (such as using insecticide-treated bed nets) as well.

Gavi and its partners continue to work towards increasing supplies of the vaccine. GSK expects to deliver 18 million doses of the vaccine by 2025, with four million doses available by late 2023, six million doses delivered in 2024, and eight million in 2025.

In pilot countries, this information has been provided through talks led by health officials and health providers, as well as meetings with community leaders, health volunteers, public service announcements and through the local media.

Scaling up supply

Meanwhile, Gavi and its partners continue to work towards increasing supplies of the vaccine. GSK expects to deliver 18 million doses of the vaccine by 2025, with four million doses available by late 2023, six million doses delivered in 2024, and eight million in 2025. Beyond that, production of RTS,S/ASO1e is expected to increase to at least 15 million doses per year during 2026–2028 thanks to a product transfer deal with Bharat Biotech, of Hyderabad, India.

However, vaccine production will still fall short of demand, so other malaria vaccines are needed to fill the gap. The most advanced candidate is R21/Matrix-M, developed by the University of Oxford, UK, and being manufactured and scaled up by the Serum Institute of India. This is currently undergoing phase 3 trials in Burkina Faso, Kenya, Mali and Tanzania, and results relating to safety, efficacy, and duration of protection in different malaria transmission settings are imminently pending. Phase 2 data published in September suggested high effectiveness following a fourth booster dose in areas with highly seasonal transmission of malaria.

It has been a long time coming, but RTS,S/ASO1e is the first vaccine to be approved for use against a human parasitic disease, and a critical new weapon in the fight against malaria.

The vaccine's developers hope it will gain WHO recommendation and prequalification during 2023, as the vaccine is currently under review by these bodies. If these milestones are achieved this year, this could make it available for use in areas with moderate to high P. falciparum malaria transmission, though potentially with an initial limited indication, as early as next year. The vaccine has also just received approval by national regulatory authorities in two countries. Other malaria vaccines are also in development, including an mRNA-based candidate by German biotech company BioNTech. It announced the launch of a phase I trial of this vaccine, called BNT165b1 in December 2022.

It has been a long time coming, but RTS,S/ASO1e is the first vaccine to be approved for use against a human parasitic disease, and a critical new weapon in the fight against malaria.