How Uganda is tackling the Ebola-like Sudan virus

After battling eight outbreaks of Ebola in the past two decades, Uganda’s health system had a plan at the ready.

- 6 March 2025

- 6 min read

- by John Agaba

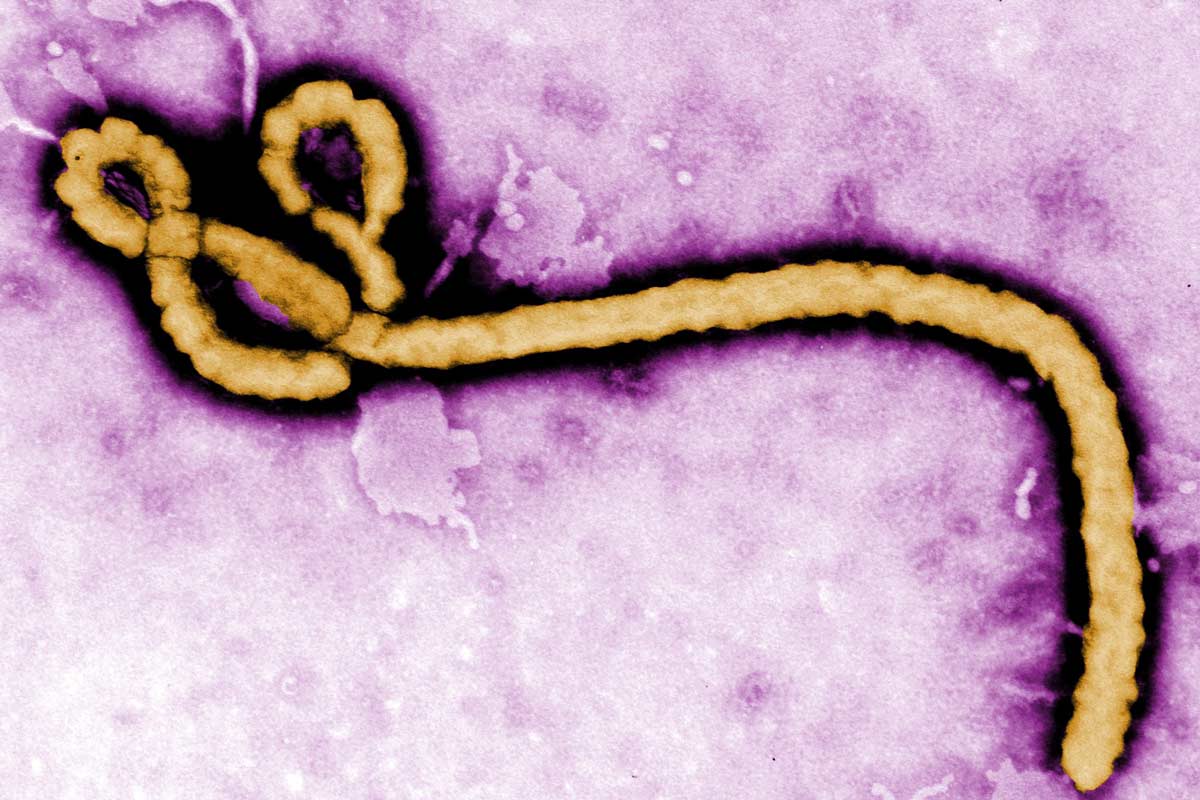

When samples tested positive for Sudan virus disease (SVD) in Uganda’s capital, Kampala, on 30 January, Dr Jane Ruth Aceng, the country’s Minister of Health, knew they needed a robust plan. The same deadly epidemic disease had killed 55 people and disrupted business and health systems in a previous outbreak in the east African country in 2022. Moreover, the virus, which belongs to the Ebola-disease causing Orthoebolaviruses, didn’t have an approved vaccine or treatment.

But after helming the battles against eight similar outbreaks since 2000, Aceng also had a pretty good idea of where to start. Prioritise contact tracing, infection control and prevention as well as treatment of confirmed cases – interventions that had yielded the most results in previous outbreaks — and they would stand a chance.

Early indicators suggest she was right. Two individuals, including the index case and a four-year-old child, have died in the outbreak, while an additional eight cases have recovered and been discharged. Two additional deaths from early February were reclassified by WHO as probable Ebola in March, bringing the caseload to 12. The Ministry is now monitoring about 265 contacts and continues to search for active cases and screen outbound travellers.

The outbreak dawns

Uganda’s Ministry of Health declared an outbreak of SVD after tests at three separate laboratories, including the Uganda Virus Research Institute in Entebbe, confirmed the virus as the cause of the index case’s symptoms. That patient was a 32-year-old male nurse attached to Mulago National Referral Hospital in Kampala, who initially developed fever-like symptoms and presented with chest pain and difficulty in breathing before he succumbed to the disease on 29 January.

Following the outbreak’s announcement, the Ministry activated its Incident Management Team and dispatched rapid response teams to identify, isolate and investigate contacts of the index case. The response team listed and monitored a total of 265 contacts, including patients and health workers at Mulago Hospital, for SVD symptoms.

By 2 February, the team had picked up on eight contacts who tested positive for the virus. Health workers treated these with experimental remdesivir, a broad-spectrum antiviral drug, and other supportive treatments at designated centres at Mulago and Mbale hospitals.

Further afield, the Ministry rallied the public to avoid contact with individuals exhibiting Ebola-like symptoms. It rallied health workers to adhere to strict infection prevention and control measures and healthcare providers to follow standard operating procedures and to promptly report suspected cases.

SVD can spread fast, and fatally – but the interventions appeared to be curbing transmission. On 18 February, less than three weeks after the Ministry announced the outbreak, the country had discharged every one of the eight cases who had to that point tested positive for the virus, barring the by-then deceased index case and one four-year-old child, who would die on 25 February.

Out of isolation

“The patients that we are discharging today are safe and free of the disease,” said Aceng when she discharged the eight. “I urge their families and communities to receive and interact with them normally.”

“The progress we have made is a testament to the hard work, coordination, and commitment of all involved,” she said. “But continued vigilance and support from all stakeholders is essential to ensuring Uganda remains free of Sudan virus disease.”

Dr Kasonde Mwinga, the World Health Organization (WHO) Representative in Uganda, said discharging the patients marked an important milestone in “our collective efforts to control the outbreak.”

Corralling Ebola in the bustling capital

All of the four related viruses that can cause Ebola disease in humans can spread via contact with animals including monkeys, chimpanzees and fruit bats, as well through direct contact with the blood or bodily fluids of infected individuals.

That could mean that outbreaks in higher-density settings might be harder to manage. Unlike the 2022 Sudan virus outbreak that first hit relatively smaller towns (in Kassanda and Mubende), the 2025 outbreak emerged in Kampala: a bustling and highly connected city of more than 4 million people. David Sseremba, a trader in the Ugandan capital, feared that the outbreak would get out of hand and disrupt business and tourism.

But it was clear pretty quickly that the Ministry was taking no chances. As soon as the outbreak was announced, the Ministry, with support from WHO, deployed its national Emergency Medical Team (nEMT) to support case management and stop the outbreak. “In previous outbreaks, we relied on mobilisation of health workers across the country, working alongside surge teams from outside the country,” Dr Rony Bahatungire, acting commissioner for Clinical Services and nEMT focal person, is quoted as saying. “However, this time, we had a fully trained, readily deployable trained team who were on site within two hours of deployment and fully constituted within 12 hours.”

“We don’t have approved treatments for Ebola,” said Dr David Kaggwa, a paediatrician and in-charge of the isolation unit at Mulago National Referral Hospital. “Even remdesivir was given on a compassionate-use basis. But we have the experience [to handle viral haemorrhagic fevers (VHFs)]. When a patient comes in, we know what to do, from day one. We treat cases depending on how they present, by managing their symptoms.”

“For instance, during this outbreak, we had two patients who were critically ill: one even moved to an intensive care unit, but we pulled them back up,” said Kaggwa in an interview with VaccinesWork. “Then, we were ready from day one. We had the medicines, the equipment and other protective gear to stop the virus.”

“The biggest challenge in 2022 was that the community (in Kassanda and Mubende districts) delayed reporting cases to health facilities when people started to show Ebola-like symptoms,” said Dr Daniel Kyabayinze, Director of Public Health at the Ministry of Health, in 2022. “Instead of coming to health facilities, the communities attributed the illnesses to witchcraft.” By the time health workers detected the virus, the disease had already spread. Verbal autopsies indicated six people had already died of the virus.

During the current outbreak, health workers at Mulago Hospital were able to detect the virus early, and start confirmed cases on treatment. According to WHO, early initiation of supportive treatment has been shown to significantly reduce deaths from the virus.

Have you read?

Eyes wide open

But not all is done. Aceng said experts from the Ministry would continue to monitor survivors for clinical complications. Health workers would also continue to give psychosocial support to the eight survivors who were discharged to ensure seamless reintegration into communities.

The Ministry has also approved protocols for testing three treatments for Ebola, including remdesivir, monoclonal antibodies and convulsant plasma. “The hope is that if there are additional cases (after the eight) then the full clinical trial would be implemented with those three treatment arms,” said Dr Ngashi Ngongo, principal advisor to the director-general of Africa CDC.

Apart from treatments, the Ministry has also started clinical trials to assess the effectiveness of a vaccine against SVD, in partnership with WHO. The candidate vaccine by IAVI is being given to contacts of confirmed Ebola patients, including health workers at Mulago Hospital, said Kyabayinze.

Dr Musoka Papa Fallah, acting director of the Science and Innovation Directorate at Africa-CDC, said health workers in the region had also developed a multi-country protocol for seven countries in the region, including Burundi and the DRC, to “dig deep” and understand the source of ‘increasing’ VHFs in the region. “But we think that there are spillover events that are going on,” said Musoka at a press briefing hosted by Africa CDC on 27 February. Rwanda and Tanzania (which border Uganda) have been battling Marburg (related to Ebola) in the recent past.