How anthropology can bring the human element to emergency outbreak response

Technical solutions to a health emergency risk failing if they don’t allow communities their say; this is where anthropologists come in.

- 9 November 2022

- 9 min read

- by Priya Joi

The largest Ebola outbreak in history happened in West Africa in 2014. It triggered an extraordinary marshalling of resources to save lives and stop the spread to the rest of the world.

The “unwillingness to embrace doubt is problematic, because doubt is an essential constitutive fact of our existence.”

That outbreak was also a critical turning point in global outbreak response, says medical anthropologist Darryl Stellmach. It saw anthropology being widely integrated into the public health emergency response for the first time.

The world has seen numerous infectious disease emergencies in recent years, including SARS and H1N1, so what was different about Ebola that saw anthropologists being brought more closely on board? In this case, says Stellmach, the rapid emergency response was solid in terms of technical detail, but failed to take into account “the local community’s suspicions about local government, and about foreign intervention in a region that saw the slave trade, colonial exploitation, diamond mining, civil war, and all of it with the interest of outside powers taking precedence”. The lack of trust meant technical solutions floundered.

“What anthropologists bring is the ‘software’ or the understanding of human factors and how social responses can affect the technical response.”

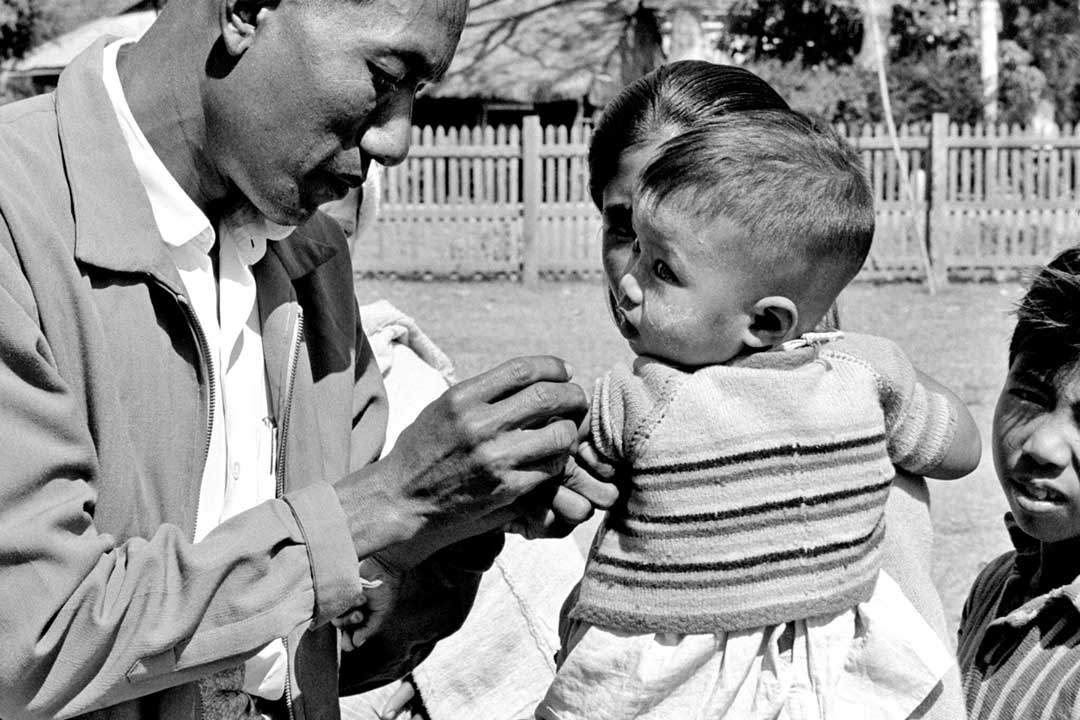

Anthropologists were able to ensure that infection, prevention and control methods, such as contact tracing or the safe burial of Ebola patients, had input from local communities. They bridged the gap between developing technical solutions and implementing them in a community that needed to take ownership of those solutions for them to work.

Facilitating dialogue and understanding so that the intervention can be adapted in ways that are locally appropriate is critical, says Stellmach. This meant, for example, adapting burial protocols in such a way as to maintain infection control while still allowing families to meet social obligations to their deceased relatives.

The Ebola emergency came on the back of a growing trend to bring the social sciences and medical humanities into public health policy. It ended up being a touchstone for how critical the social science perspective can be in an emergency.

During the outbreak, the roles of anthropologists were negotiated in real-time, but Stellmach says that ideally an intervention would have pre-defined roles and resources and people. At Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), where he began working in 2003, Stellmach and colleagues pioneered the “anthro-epi tandem”, which he describes as “a very simple, robust little team, consisting of a field epidemiologist and a field anthropologist, offering two pairs of eyes to any problem. But they brought two different views on the same problem, offering a complex perspective that led to more integrated, robust recommendations on how to solve it.”

Emergency response has interested Stellmach his whole professional life. Now an academic at the University of Tasmania, Australia, when Stellmach began his undergraduate studies in anthropology he became so fascinated with outbreak response and the aid sector that he finished his studies and immediately went to work in the relief and development sector.

During that time, he realised how the global health community had honed the technical aspects of outbreak response yet can still misjudge how people will respond to these measures. “We know how to track the outbreak, to calculate incidence rates, characterise the pathogen and develop vaccines – COVID-19 has revealed just how much we can fast track so that all the ‘hardware’ is there.” But, he says, “What anthropologists bring is the ‘software’ or the understanding of human factors and how social responses can affect the technical response.”

“The most successful outbreak responses are the ones where both the responders and the community members themselves make a genuine effort to understand one another and to understand one another's position. And that’s done through dialogue.”

Stellmach took a year away to complete a master’s in medical anthropology before returning to MSF in 2010. While he was head of mission in Nigeria, the country was battling multiple outbreaks including cholera, measles and meningitis. With few resources to respond to everything, and every issue seemingly urgent, Stellmach kept asking himself, “How do you know an emergency when you see it?

“Epidemiologists could tell me where there were disease hotpots, but as for the rest of the evidence even when it was available it wasn’t always reliable. So we were cobbling together a little patchwork of evidence to make decisions about where to commit resources. In the end we were relying on intuition, which can be useful, but to me it was an unsatisfactory way to commit thousands of dollars in supposedly lifesaving operations,” he says.

Have you read?

To understand that better, Stellmach made this question the focus of his DPhil at the University of Oxford, which he finished in 2016. His work revealed some of the complex decision-making that happens behind the scenes of an emergency response: practitioners must balance qualitative and quantitative evidence – some of it contradictory – against social, political and moral considerations. An emergency response is always provisional, and always subject to revision.

While there are criteria to determine what is a global health emergency, over the past few years, health institutions have been criticised for their decision-making. For instance, the World Health Organization was criticised by some for ‘overstating’ the risk of the 2009 H1N1 swine flu pandemic, that turned out to be fairly moderate. Similarly, the recent global monkeypox outbreak really only caused alarm and drew attention when it spread to countries outside of Africa, despite African epidemiologists warning of changes in the virus for years.

Ultimately, says Stellmach, it’s important to remember that emergencies operate on different registers simultaneously. In addition to being a biological threat, a public health emergency can be a social, political, economic and moral threat too. With an infection such as COVID-19, “there is a huge element of politics and diplomacy at play in deciding whether or not it is an emergency,” he says. With some emergencies, such as Ebola, there is the overwhelming biological threat of a disease that has a high death rate. COVID-19 brought a significant social threat in reorganising our working habits, the economy and the way we travel.

When such a virus also threatens to reorder or totally change the things we value such as our freedoms and entitlements, it upsets “the moral order of the universe”, Stellmach explains, and much of the public reaction to COVID-19 was a moral outrage that the freedoms we value were under threat. With monkeypox, there was a classic “moral panic where the threat was grossly amplified to all of society, but the tone of panic was completely out of kilter with the expert perception of risk.”

While global health can focus inordinately on emergency response, there is a vast swathe of public health interventions, from road safety to reducing alcohol or tobacco consumption, to which anthropologists can, and often do, bring their experience to bear. So should anthropologists be brought in closer to the decision-making process for public health measures?

Stellmach is reluctant to characterise anthropologists as “another layer of expertise to be brought into a circle of experts”. Too often there are too many technocrats and not enough grounding in community experience, he says. “The strength of the anthropological approach is being able to ground an intervention in the everyday reality of people. Sometimes that can mean translating cultures or experiences to one another. Just as you need to bring community understandings to the technocrats, you also need to translate the culture of the technocrats to the community.”

He adds: “The most successful outbreak responses are the ones where both the responders and the community members themselves make a genuine effort to understand one another and to understand one another's position. And that’s done through dialogue.”

“One of the failures in public health communication over the last half century is the presumption that if people have wrong information or are concerned about a given issue, then the solution to that is just to give them the right information, and then they will make the right decision. Evidence shows that’s actually not how people make decisions.”

One area where scientists and part of the population can seem to be speaking at odds is vaccine hesitancy. Scientists can seem confounded as to why some people are against lifesaving vaccines that have proven to be effective, and those who are hesitant can feel that their concerns are not being taken seriously enough.

There is no universal reason for opposition to vaccines, he points out. Some people do not want to take them because of a political perspective, others may be hesitant from a biological perspective, and others may have a moral objection: “You can’t tell me what to put in my body.” Understanding and categorising those hesitancies is what social researchers can contribute to public health.

“You can’t necessarily counter these concerns with more data,” he says. “One of the failures in public health communication over the last half century is the presumption that if people have wrong information or are concerned about a given issue, then the solution to that is just to give them the right information, and then they will make the right decision. Evidence shows that’s actually not how people make decisions.”

“People who feel that their way of life and their freedoms are under threat are not going to react to scientific arguments. Here, we need people who are experts in this aspect of society and social understanding,” says Stellmach.

Another issue that runs alongside this dissonance, he adds, is that human beings often seek certainty. The sciences have been held up as a source of certainty but they don’t offer that. Instead, they offer probabilities and degrees of certainty. In public life too, we expect certainty from politicians, which means that complex health and political issues lose their nuance when communicated publicly. The “unwillingness to embrace doubt is problematic, because doubt is an essential constitutive fact of our existence,” he says.

Science communicators need to get better at conveying uncertainty and risk, and the public need to acknowledge and live with uncertainty, such as understanding that sometimes vaccines can cause negative side effects and that processes should be in place to support those people, and that overall vaccines contribute vastly to the public good.

It’s also important to understand another facet to hesitancy, which is that trust in public institutions is low, he says. People often base their healthcare decisions, including vaccination, not on data, but on what the people they trust say. These might be family members, friends or a handful of community leaders, or people they resonate with in the media. This is why community health workers had, and continue to play, such a critical role in vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The onus is not just on communities and individuals to see it as their personal and social duty to get vaccinated; institutions of power need to play their part too. “Overcoming hesitancy will mean rebuilding trust in scientific institutions, trust in political institutions and trusted professions. That trust has been shaken often.”

Ultimately, our public discourse requires far more nuance than it currently has, says Stellmach. Few issues are black and white, and as happened with Ebola, acknowledging the grey may actually build more trust in people who can see that health interventions don’t always work as intended. The failure to acknowledge that may destroy trust in health messaging rather than engender it.

This will also mean media communication that is more complex, however. “It can be difficult to convey nuance in a news environment that favours a short, snarky tweet over more detailed exploration.”