Five things you need to know about the H5N1 bird flu outbreak

The current bird flu outbreak – the biggest ever – is causing mass deaths in birds worldwide, and is starting to affect mammals. How worried should we be?

- 7 February 2023

- 7 min read

- by Priya Joi

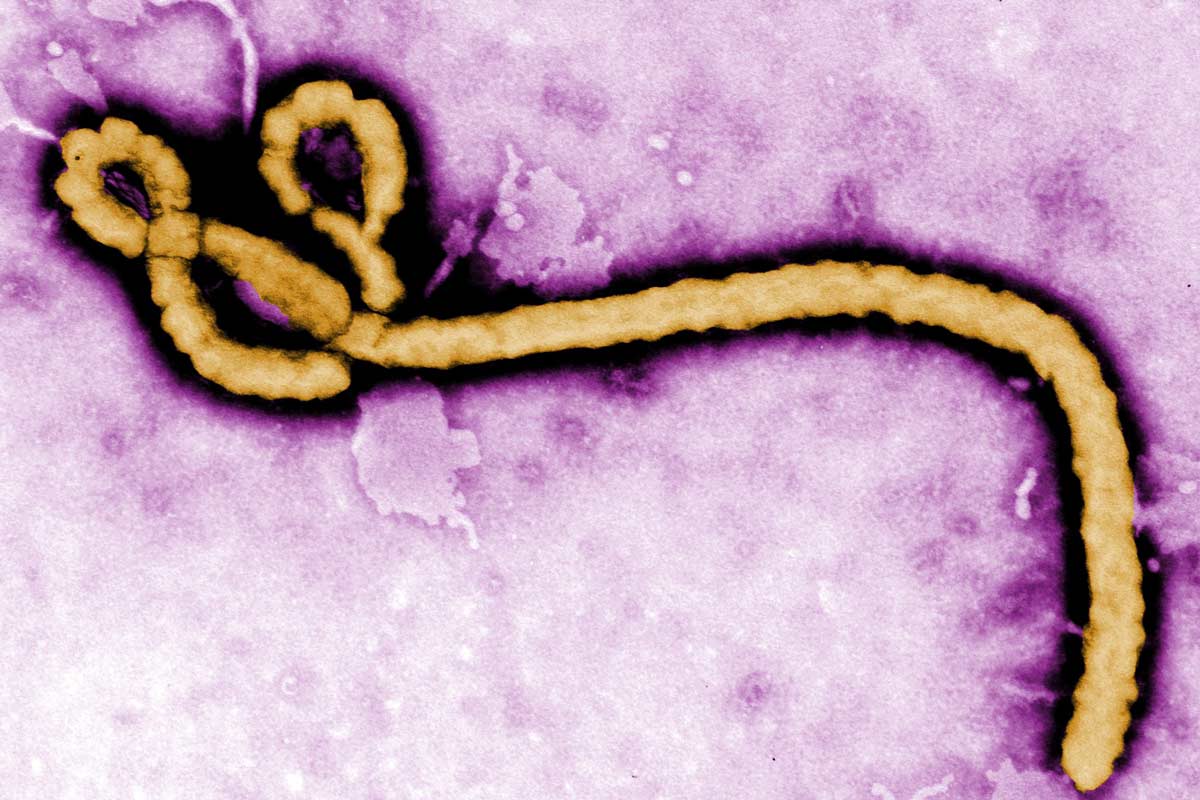

Bird flu has long been on the radar of infectious disease specialists. In 1997 H5N1 poultry outbreaks in China and Hong Kong infected 18 people, killing six. The virus had been detected a year previously in domestic waterfowl, in Southern China. This virus would go on to cause more than 860 human infections with a death rate of over 50%.

Reassuringly there does not yet seem to be evidence that the virus has spread from mammal to mammal.

The threat of it causing a pandemic has never been too distant. Yet H5N1 has been wiping out bird populations around the world with increasing ferocity and spreading to some mammals, causing scientists to wonder whether the risk to people is rising.

1. The pandemic threat from bird flu is high – it may have caused the 1918 flu pandemic

In 1918, a pandemic influenza strain emerged that was so contagious it infected a third of the world's population and became one of the deadliest pandemics in history. Some researchers now believe that this pandemic virus could well have been a bird flu, which had most probably mutated to move from the lower respiratory tract to the upper airways, making it much more transmissible.

The pandemic threat from bird flu remains high. Since the 1918 flu, there have been three flu pandemics – H2N2 in 1956-7, H3N2 in 1968 and H1N1 in 2009 – and it was widely assumed that the next pandemic would be caused by influenza.

The difference between 1918 and now, however, is that back then the First World War was raging, and tens of thousands of exhausted troops were traversing continents, allowing the virus to spread between people with stressed immune systems. At the time, there were no vaccines, nor any antivirals. However, while we have these additional tools to fight a potential bird flu pandemic, these are not easily rolled out nor always effective.

2. The virus has been found in mammals

For the past year, the largest ever outbreak of the H5N1 subtype of the virus has spread across farmed poultry and wild flocks in the US, Europe and Asia. It has caused mass mortality, with around 15 million domestic birds dying from bird flu over the past year and a half. More than 193 million have been culled to stop the virus spreading.

The virus has now been detected in a range of mammal species: mink in Spain, foxes and otters in the UK, grizzly bears and dolphins in the US and seals in the Caspian Sea. This has caused concern that the virus may have mutated to become more easily spread in mammals – including people – but this spread is not evidence of that yet, said Prof Mark Fielder, Professor of Medical Microbiology, Kingston University. Reassuringly, he adds, there does not yet seem to be evidence that the virus has spread from mammal to mammal.

Dr Alastair Ward, Associate Professor of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Management, University of Leeds, said many of the mammal species affected are scavengers – this means that most likely, the animals scavenged infected wild bird carcasses, which may have had very high viral loads. "Such high exposure is likely to have overwhelmed the mammal's immune system, resulting in infection. There is currently no reason to suspect that the jump is due to a change in the virus's genetic make-up."

3. There is no evidence yet that there is a threat to people

For now, H5N1 only rarely infects people – mostly through contact with infected birds – and few cases have been recorded of it being passed from one human to another. The virus binds to receptors in the upper airways of birds that are less common in mammalian upper airways, which means it is much harder for infected mammals to spread it. But the risk, say scientists, is that the more often bird flu infects mammals, the more chance it has to evolve to be able to invade mammalian airways better.

Speaking to Science, Tom Peacock, a virologist at Imperial College London, says that virus samples taken from infected mink in Spain showed genetic mutations that have also been seen in samples from other infected mammals. This is worrying because it can help H5N1 better replicate in mammalian tissues. This could be the lightning fuse that gives it the ability to spread between people.

However, while being cautious and watchful, it's important to keep these developments in perspective, Ian Barr, deputy director of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza in Melbourne, Australia, told Gavi last year.

"There's a number of changes that would need to happen, and even then, the virus would probably need to be passed between humans for a while to build up real transmission capability. So, it's not just a snap of the fingers; it might take years, or decades, or it may never happen. But I don't think we can be so blasé that we just ignore these things."

4. Vaccines are available, but tough to scale up

Vaccinating birds against flu is tricky to get right. In 2017, China began mandatory vaccination of poultry against an H7N9 strain that was able to spread to people. This massively reduced the spread of the virus in birds, and cut the number of human infections to zero.

Have you read?

However, H5N1 infects more types of birds – H7N9 is mainly a problem in chickens – making vaccination more challenging this time around. Moreover, public health officials are worried that if vaccination isn't carried out properly, it could allow the virus to circulate at a low level, actually increasing the chance of mutations and spreading to people.

While there are bird flu vaccines to protect people, and several in development, so far "they do not produce really good, strong immune responses in humans," Ian Barr told Gavi. "We haven't yet tried mRNA vaccines with these viruses; we know they work to some degree, but how well they'd work and what level of protection they'd induce is still an open question."

Even though H5N1 vaccines have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration, scaling up could take many months as all but one are produced by incubating each dose in an egg (the same way that human flu vaccines are made). The non-egg-based H5N1 vaccine could produce 150 million doses within six months of the declaration of a pandemic, but this still wouldn't be enough to protect the world.

5. Work is underway on disease surveillance, but may not be enough

Given the threat of a bird flu pandemic it's clear that preparedness is critical, say scientists like Marion Koopmans, head of viroscience at Erasmus Medical Centre, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. To better use big data and be on the front foot with infectious threats, rather than playing catch-up, Koopmans and colleagues set up the Pandemic and Disaster Preparedness Center (PDPC) as a collaboration between the Erasmus Medical Centre, the Erasmus University and the Delft University of Technology. "We're looking at what the drivers are for those emergent pathways , and how we can spot major change – hotspots – in these ecosystems that would favour pathogen emergence," she told Gavi.

With inadequate systems in place to detect and halt outbreaks in animals farms, Koopmans – who investigated the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic for the World Health Organization – warned: "We are playing with fire."

Thijs Kuiken, an expert in avian influenza also at Erasmus University Medical Center, told The New York Times that "farms for pigs – another species susceptible to influenza – should also be surveilled for bird flu. People interacting with wild birds and animals, as well as susceptible species of pets like ferrets, are also at higher risk. It's not enough to detect, though: Suppression would require a major effort and global coordination."