Eyes wide open: community awareness is Nigeria’s best prophylactic against sleeping sickness

Human African trypanosomiasis is a stealthy killer. But persistent efforts to educate at-risk communities are paying off, finds Adetokunbo Abiola in Delta State.

- 13 December 2024

- 6 min read

- by Adetokunbo Abiola

One morning in December, in Abraka, a town in Nigeria’s Delta State, Ifeoma Onoriode sat with her six-year-old daughter, Monica, outside their home. Next to her lay a long, curved blade.

“I have to cut the bushes around the house with my cutlass. It is not an easy thing to do, because I’m not used to it,” the 34-year-old told VaccinesWork. “But I have to do it. Apart from keeping my surroundings clean, it does something good for me and the family – to prevent the presence of tsetse fly, which causes sleeping sickness.”

This was a new resolution for Onoriode. Recently, health workers had shown her a documentary film about human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) – a tsetse fly-borne parasitic disease commonly known as sleeping sickness – which had managed to convince her to take prevention seriously.

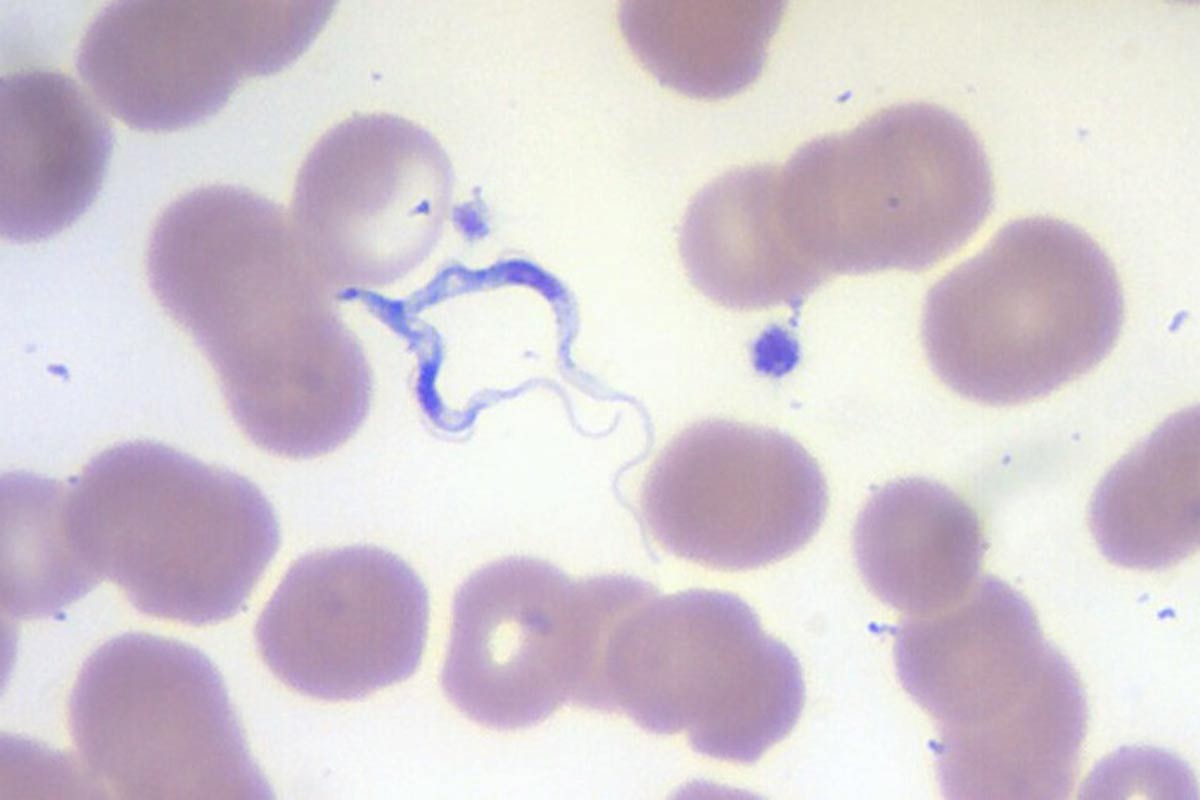

The infection is a slow and stealthy killer. A tsetse fly bite might cause a raised sore in the first instance, followed by headaches and on-and-off fevers, itchy skin, fatigue, lack of appetite and swollen lymph nodes. These diffuse and generalised symptoms might persist for a year or more without medical intervention. Then, with the infection reaching the brain and central nervous system, the disease’s second stage begins. Patients have reported inverted sleep cycles – wakeful at night, drowsy in the day – anxiety, mood instability, hallucinations and delirium, and phantom sensations, like unusual sensitivity in the skin. Tremors, slurred speech, seizures and finally, coma, lead, ultimately, to death.

“The advice of health officials has been on my mind for a long time – especially one of them, an elderly woman, who told me the story about the repercussions of sleeping sickness, confusion and other problems. I now cut the bush around my house and also use bed-nets for me, Monica and my husband. Nothing will change my stance again, especially as health officials say Abraka is an endemic area for sleeping sickness,” Onoriode said.

Still out there

For the Nigerian health system, preventing HAT is an ongoing project, even though cases of the disease are rarely documented as confirmed – the last case reported by Nigeria to the World Health Organization (WHO) was in 2012.

But some scientists say cases are undercounted. Nigerian scholar Elizabeth O. Odebunmi and colleagues set out to estimate its actual prevalence rate in a review study – published as a preprint – earlier this year, pegging it at 3.6% overall. Their findings suggest the country still has a way to go until it reaches the elimination end-line, conventionally defined as fewer than 2,000 reported cases annually, and no more than 1 case per 10,000 residents in areas at moderate or high risk.

The study co-authors also suggest that African animal trypanosomiasis prevalence may be as high as 27.3% – a figure with significance for human health, as scientists believe the tsetse fly vector can pick up the causative parasites behind the human illness from some animal hosts.

In humans, trypanosomiasis has a close to 100% mortality rate if left untreated, and the WHO estimates that about 55 million people in sub-Saharan Africa remain at risk of HAT infection. But the disease does appear to be in retreat as control programmes press forward: annual counts of new reported cases have fallen 97% in the last two decades.

Dr Amos Ogbeide, a consultant microbiologist with the Specialist Hospital, Benin City, Edo State has been actively involved in tackling it in his vicinity. “Sleeping sickness is still in Nigeria, even though the last reported case was in 2012, because trypanosomiasis is present in animals around us,” he explained. There is no vaccine, but other means of prevention have proven effective.

“The measures we take to tackle HAT in Nigeria include vector control: controlling the tsetse fly population through the use of insecticides and other methods, [and] mass drug administration: distributing medications, such as ivermectin, to communities at risk of HAT.

“We also educate communities on HAT prevention and control measures, such as avoiding tsetse fly bites and using bed nets.-The communities are located around Benin City, Asaba, Warri, and others.

“We frequently encourage community people to engage in practices related to HAT prevention, such as clearing overgrown bushes around houses and using insecticide-treated nets. The good news is that it has led to the reduction of cases of sleeping sickness,” Dr Ogbiede told VaccinesWork.

Have you read?

Eyes wide open

Hafsat Suleiman Mohammed, the Communication Chief, Nigeria Institute for Trypanosomiasis Research (NITR), Kaduna says there’s good reason that the health system is not sleeping on trypanosomiasis.

The last formally diagnosed case was recorded in Delta State in 2012, he confirms, and Nigeria has its sights set on the WHO-set target of elimination by 2030. “But the disease is still in Nigeria,” he added. And managing the illness has not been without challenges.

The commonly-prescribed drugs for suspected patients can have high toxicity, poor efficacy and “undesirable routes of administration,” Mohammed says. Moreover, drug resistance is a rising worry.

“However, there is good news now as a new drug called fexinidazole has just been developed and adopted as an oral and effective treatment for sleeping sickness,” Mohammed told VaccinesWork.

Potentially more impactful still is community awareness. As a consequence of health system communications pushes, ordinary people such as Veronica Omo Agege, a 34-year-old mother of two children aged four and six in Abraka, are aware the disease is still in Nigeria, and they’re taking proactive measures.

“I know the disease you’re talking about,” she said, in an interview with VaccinesWork. “Health workers from hospitals tell us it may still be in our area. It causes confusion and drowsiness.” She says she and her family wear thick protective clothing as a physical barrier to the vector.

“We stay away from dark colours that bring tsetse flies, which cause the disease that makes people sleep anyhow. We also keep away from bushy areas during all times of the year, especially during hot weather, when tsetse flies rest and may bite if disturbed. In fact, I cut the bushes around me. Not only that, my husband, James, sprays our vehicle before use, and my children use bed-nets,” Omo Agege told VaccinesWork.

Ekperi Akinabo, a 46-year-old mother of four at Abraka, is also aware of the danger posed by sleeping sickness.

“I’ve heard about the disease. They say it causes people to sleep. Some say it brings confusion and drowsiness. Health people say it still exists in our area. Because of the way they talk to us, I adopt protective measures. I don’t want any of my four children to contract the disease.

“From what I hear, it can lead to death, if not treated, so I make sure my children stay away from bushy areas, where there is danger of tsetse fly. We use bed-nets. I also advise my husband to do the same thing. In addition, I cut the bushes surrounding our house regularly,” Akinabo told VaccinesWork.