In Ethiopia’s Afar region, a change of messenger boosts immunisation uptake

A project to recruit and train religious leaders to deliver information on vaccination has made strides, health workers say, among a population renowned for hesitancy.

- 29 April 2024

- 5 min read

- by Solomon Yimer

When vaccinators visited Hawa Behaba's village in Dulessa district, part of Ethiopia's north-eastern Afar region, the mother of five used to hide her children. "I thought the vaccines would make my children sick, and that [vaccination] went against my faith," Hawa recalls.

Her children frequently fell sick. She tried to ease their symptoms using traditional remedies, and on occasion, was compelled to visit the health centre for treatment.

“Modern science and medicine do not conflict with our religion, and a balance can be struck between culture, religion and modern health care,” Hakim tells VaccinesWork. “The human is the centre of Islam. Our religion’s advice is to take care of our well-being to protect our children from disease.”

"The health workers would often tell me that their illnesses were a result of not receiving proper vaccinations," she recalls. "But I kept refusing." Community health workers who tried to change her mind got nowhere. For years, the children remained completely unvaccinated.

That all changed when the messenger changed.

Immunising Afar

Behaba's is not an isolated case. The vast majority of the population in Afar is drawn from Muslim pastoralist communities, who, tending livestock for a living, move frequently in search of pasture for the animals. Their mobility makes immunisation challenging. Meanwhile, worries about vaccination, associated with cultural and religious beliefs, are common. Afar has one of the lowest immunisation rates in Ethiopia.

"Developing and pastoralist regions, internally displaced people, newly formed regions, and conflict-affected areas had the highest prevalence of zero-dose children," found a recent BMC Public Health study from Ethiopia. By the researchers' assessment, Afar sat at the overlap of three of those categories, being a pastoralist, developing and conflict-affected area.

"One of the biggest challenges we face is the constant movement of the pastoralist communities," Medina Mohammed, a health worker at Tirtira Health Centre, explains. "This makes it difficult for us to track them and provide consistent vaccination services." Parental refusal "due to cultural and religious beliefs" presents an additional barrier, she says.

Credit: FSA

In a bid to ensure that no one is left behind, Medina and her team of health workers in Tirtira kebele implemented a number of strategies, conducting awareness campaigns, utilising community volunteers to locate unvaccinated children, and addressing issues concerning zero-dose children and drop-outs.

However, obstacles remained – particularly in overcoming cultural and religious beliefs that obstruct vaccination efforts within the community.

Then, in August 2022, the CORE Group Polio Project (CGPP) and the Friendship Support Association (FSA) – with funding from Gavi – hosted 33 religious leaders from four districts in Afar at an advocacy workshop on immunisation in Awash town.

"In this case, recognising the true influencers in a community is crucial. In Afar, religious leaders are trusted and respected individuals who play a significant role in shaping societal norms and values," says Bayush Gizachew, the project's coordinator for FSA.

Preaching – and listening

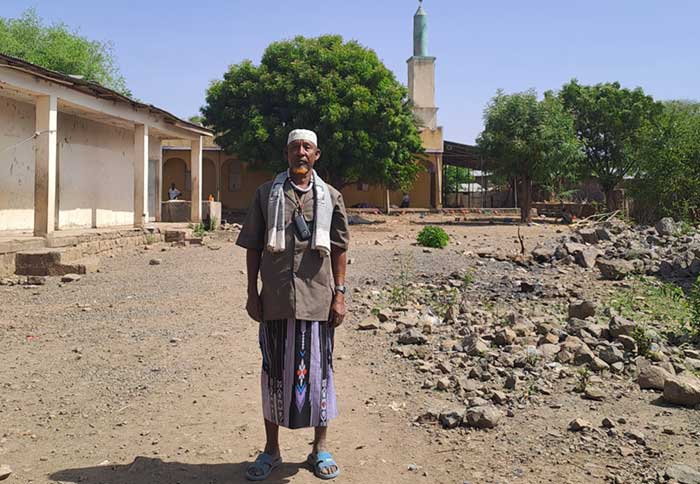

At 70 years of age, Shek Mohammed Hakim is a respected religious leader in Tirtira kebele, Dulessa district. When health authorities, together with the FSA project, reached out to invite him to educate his community about the importance of immunisation, he accepted gladly.

"I saw this as another chance to serve my community and improve their health," Hakim says.

Following training, Hakim and other religious leaders in the district began educating their community about the importance of vaccines and health care, emphasising that immunisation did not contravene religious teachings.

One morning he approached a group of mothers from the village, who had gathered to fetch water. Behaba was among them.

Credit: Solomon Yimer

He had information to share – but he was listening, too. During the session, Hakim gained a deeper understanding of the work needed to correct misconceptions about vaccinations within communities. "Many fear vaccinations will cause illness to their children, some think it will make them become skinny, while others oppose vaccines due to religious reasons," he says.

Have you read?

"The community often thinks that sickness is God's will, and if their children are healthy, vaccinations are unnecessary," Hakim explains, noting that children in his village frequently fall ill.

His training had prepared him for their doubts. "Through our surveys, we have identified community attitudes and provided [the enrolled religious leaders] with vital key messages to address these concerns," Gizachew explains.

On Fridays after prayers, and at community gatherings like funerals and weddings, Hakim continues to educate the community about different diseases and how vaccines can help prevent them.

"Modern science and medicine do not conflict with our religion, and a balance can be struck between culture, religion and modern health care," Hakim tells VaccinesWork. "The human is the centre of Islam. Our religion's advice is to take care of our well-being to protect our children from disease."

Generally, the community has welcomed his guidance, he says. "As we are always together with them on every occasion – in sad and happy times – they respect us and trust us and accept our words."

Behaba changes her mind

His word on its own is not always quite enough. Hakim remembers a community member who had resisted vaccinating his children. But then, during a measles outbreak, the unvaccinated children suffered more severe complications compared to vaccinated ones. This incident helped convince the man and other community members about the importance of vaccination.

It's the combination of providing accurate information and personal anecdotes, Hakim says, that has resulted in many "successfully changed attitudes towards vaccination" within the community.

Behaba is another example. She says she has learned that vaccines are safe and necessary to protect her children from deadly diseases. She has become an example for the community: all her children are vaccinated. More than that, she has become an advocate for vaccination, sharing her own experience and encouraging other parents to get their children protected.

"[Religious leaders'] involvement has been crucial in helping us overcome one of the most significant challenges in providing immunisation services," says Mohammed, the health worker.

Local health authorities say they have noticed better results in the overall immunisation service, including an increased demand for vaccinations and immunisation coverage rates in the community.

"Since the implementation of the project in our district, we have seen a marked improvement in various areas. Drop-out and defaulter rates have decreased, zero-dose children have been identified, and overall vaccine coverage has increased," said Mohammed Suliman, head of Dulessa Health Center.