Cutaneous leishmaniasis spikes in Pakistan as treatment stock-outs hit northwestern region

It’s a disease of the poor – but with drugs scarce in public facilities, patients are having to pay out of pocket for increasingly expensive medicines on the private market.

- 15 February 2024

- 6 min read

- by Adeel Saeed

Carrying his three-year-old son piggyback, Hashim Khan travelled several kilometres across rugged hill terrain to reach the major hospital of Mohmand district, near the Pakistani border with Afghanistan. The reason for their journey was a painful, itching, stubborn lesion on the boy's cheek.

The visibly fatigued father's worries only grew when hospital staff told him that the child had cutaneous leishmaniasis, and that the first-line drug needed for its treatment was out of stock.

“I am a daily wager and cannot afford to skip earning for 20 days to shift my son to Peshawar for getting Glucantime jabs and dressing.”

- Hashim Khan, father

Glucantime, a pentavalent antimonial, is the major therapy for all kinds of leishmaniosis. Medics advised Khan to try to buy the medicine from local market, or otherwise to take the boy to a tertiary care hospital in Peshawar, the largest city in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

Khan raised loans from his relatives to buy 30ml of Glucantime ampoules from the market at a cost of 3,200 Pakistani rupees (US$ 11.46). Financially speaking, it was the less ruinous option.

"I am a daily wager and cannot afford to skip earning for 20 days to shift my son to Peshawar for getting Glucantime jabs and dressing," Khan told VaccinesWork.

Sandfly-borne plague

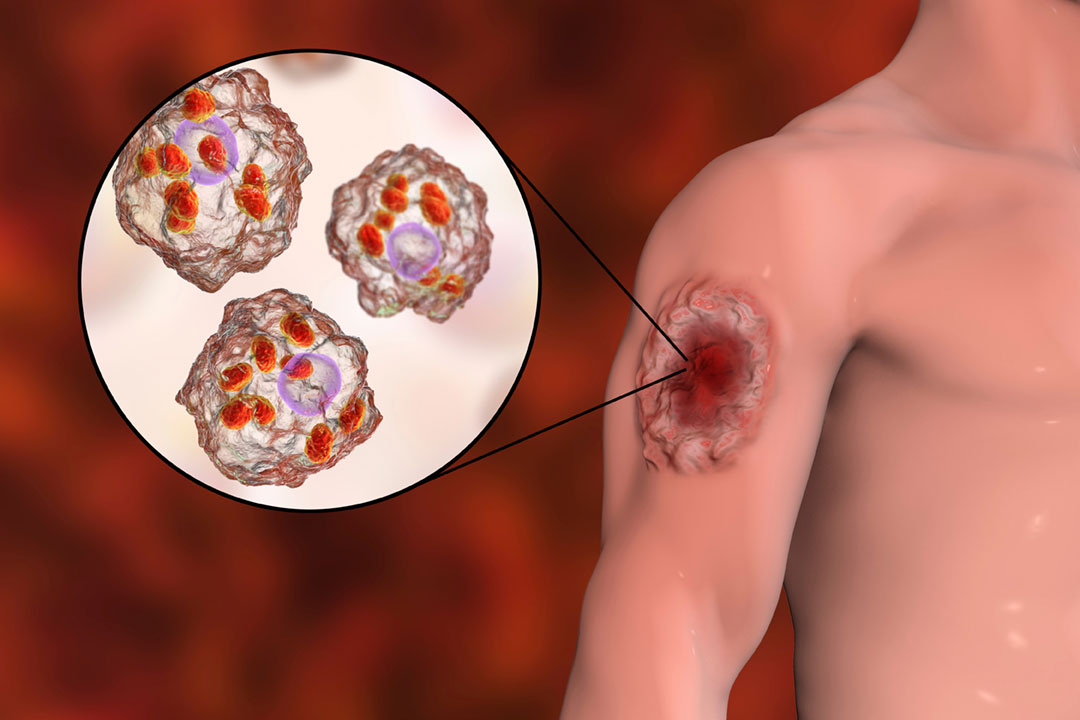

Leishmaniasis is a parasitic disease transmitted by the bite of phlebotomine sandflies, and exists in three forms – visceral, which is deadly when untreated; cutaneous, affecting the skin; and mucocutaneous, which affects the mouth, nose and throat. In all of its forms, leishmaniasis plagues mostly poor communities, and is classed among the Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs).

In Pakistan, cutaneous leishmaniasis is especially prevalent in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and Baluchistan provinces.

KP, which registered nearly 25,300 cases in 2023, is currently facing an acute shortage of Glucantime injections, which has made it very difficult for patients to receive free treatment from public sector health facilities.

Shortages stop treatment

"We are short of Glucantime vials due to utilisation of the existing stock, and unable to treat patients whose numbers are on the rise during winter season when the incubation period of sand fly bite matures," said Dr Waseem Marwat, a dermatologist at Lady Reading Hospital (LRH) in Peshawar, the largest medical facility in KP.

LRH is receiving a glut of chronic cases of leishmaniasis from district hospitals on a referral basis, he said, but staff are stymied by the drug shortages. Patients are asked to procure Glucantime or miltefosine tablets privately, but the drugs are costly, and many of them can't afford to, he explained.

Credit: Adeel Saeed

A 20-day course of miltefosine tablets costs around 16,000 Pakistani rupees (about US$ 58), while a 21-day injection course of Glucantime costs around 21,000 Pakistani rupees (US$ 76). When demand rises, so do prices, Dr Marwat pointed out.

In cases of severe ulcerative skin leishmaniasis, Dr Marwat added, medicine has been arranged for patients through donations from medical staff and local philanthropists.

"The health department provides Glucantime injection free-of-cost to patients and sometimes faces shortages due to our dependence on international organisations for arranging the medicine," said Dr Rafiq Hayat Malezai, District Health Officer (DHO) Mohmand District.

New stocks were expected to take a couple of months to make it to the country, he told VaccinesWork.

Steep rise in incidence

Overlooked for decades, CL suddenly came into spotlight in 2018 when an outbreak of the contagious disease infected some 28,000 people in KP. In response, 180,000 vials of Glucantime were procured through WHO, Dr Rafiq recounted.

That substantial stock of medicine was in use in the province for around four years. But in December 2023 it ran out, he told VaccinesWork.

Meantime, the CL burden has been rising precipitously. Epidemiological data released by the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response System, part of the KP Public Health Department, reveals that the province's caseload rose from 3,177 in 2021, to 18,180 cases in 2022, and again to 25,273 in 2023.

Taking notice of the alarming surge, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), which supports several CL clinics in Pakistan, issued a statement late last month.

"The increase in incidence of CL in 2022 to 2023 has been exceptional, with twice as many patients registered in our Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) facilities, 95.0% in Bannu and 75.5% in Peshawar," Suzette Kämink, MSF cutaneous leishmaniasis expert, was quoted as saying.

A similar trend has been seen in Balochistan, with 69.9% more cases at MSF's Kuchlak clinic alone.

Flood plains and border zones

Citing the devastating floods of 2022 as a reason for the increased burden of vector-borne diseases in his province, Dr Amir Raisani, Incharge Vector Control Programme Baluchistan said that in fact CL infections are likely under-reported, due to lack of awareness among people.

In an interview with VaccinesWork, Dr Raisani said the Baluchistan Health Department had a stock of Glucantime ampoules supplied by UNICEF, and now efforts are underway to effect a new procurement via WHO.

Have you read?

He added that sharing a border with Iran and Afghanistan, the latter carrying one of the highest burdens of leishmaniasis in the world, leaves his part of Pakistan firmly in grip of the infection, with certain districts severely affected.

Treatment alternatives?

Early-stage infection can be treated with cryotherapy – the application of small volumes of liquid nitrogen, at a temperature of about -196°C, to the affected portion of skin once or twice a week for up to six weeks. The inverse, thermotherapy, the application of heat to the affected skin, is also practised, says Muhammad Amjad, Focal Person Vector Control Programme for Mohmand District.

But when the papule develops into a sore lesion, the patients are advised to visit major hospitals or treatment centres established by MSF in Peshawar, he went on to say.

"God's mercy"

Shots sold as Glucantime to patients from local markets amid shortages in public facilities can be of substandard or counterfeit quality. Occasionally, these poor quality alternatives can be "highly painful", shares Dr Ikhtiar Wali, who serves at a Basic Health Unit (BHU) in Michini, a suburb of Peshawar.

"We are administering antibiotics due to lack of Glucantime, and in case of non-improvement, the patient is advised to arrange medicine from market or visit Peshawar city," he said.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa’s cutaneous leishmaniasis case-count rose from 3,177 in 2021, to 18,180 in 2022, and again to 25,273 in 2023

But with so many CL patients too poor to afford that, many are "leaving themselves on God's mercy," Dr Ikhtiar recounts.

Stock-outs set to ease

"The World Health Organization is short of Glucantime injections due to our biennial closure that ended in December 2023," said Dr Babar Alam, who heads WHO's sub-office in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

"Our consultations with the Health Department and MSF for early overcoming of drug shortage is in progress, but arrival of new stock will take a couple of months," he acknowledged in a phone interview.

"Health Department of Khyber Pakutnkhwa has moved a summary demanding purchase of new stock of Glucantime through WHO at a cost of 40 million Pakistani rupees (US$ 144,927) for supplying to hospitals," clarified Dr Irshad Ali Roghani, Incharge Vector Control Programme KP.

Options to acquire Glucantime on humanitarian grounds through international organisations like MSF and the Marie Adelaide Leprosy Center are also being pursued, he added.

Homegrown R&D

Dr Roghani also disclosed that in a bid to ease dependence on imported Glucantime vials, the KP government is looking into locally manufactured medicines. A reputed public sector university has been assigned the task of research for the preparation of a new anti-leishmaniasis drug.

"Taking cognisance of difficulties faced by patients due to shortage of Glucantime injections, MSF is also carrying out clinical trials in Pakistan to look for other options including cryotherapies," said Fahim Wazir, a pharmacist and researcher with MSF.

So far, 386 patients across two treatment centres in Quetta have enrolled in the CL clinical trial. Another clinical trial site was authorised in January 2024.