8 things we have learned from the COVID-19 pandemic

Next week marks three years since the World Health Organization characterised COVID-19 a pandemic. From immunity and vaccine efficacy to virus evolution and Long COVID, here’s what we now know.

- 9 March 2023

- 5 min read

- by Priya Joi

The pandemic has killed nearly seven million people

By now, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), 6.8 million people have died of COVID-19 and there have been 758 million infections. While many people may have moved on from thinking about the virus, the fact remains that there are nearly 70,000 new cases every day – which is probably an underestimate given that people are less likely to get tested, and many countries have been unable to continue to invest in detailed surveillance.

WHO cites the “unprecedented stress” from fear of the virus, social isolation and loneliness, suffering from infection, losing loved ones, and financial and economic worries as stressors that have led to a rise in mental health conditions. Among health workers, exhaustion has been a major trigger for suicidal thinking.

Long COVID means we will be dealing with the collateral damage for years

The lingering effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection – in the form of Long COVID – have caused a kind of shadow pandemic of people with a wide variety of symptoms including fatigue, brain fog and muscle pain that are often untreatable. The numbers of people affected are devastatingly high – a study in JAMA put it at 15%, but a meta-analysis in The Lancet that pooled 194 studies found that as many as 45% of people who got COVID-19 had at least one recurring symptom four months after their initial infection.

For some, these symptoms are frustrating, but they are still more or less able to live their life normally. For many others, symptoms are so debilitating that they have not been able to resume work, to the extent that economies have been affected through a loss of productivity.

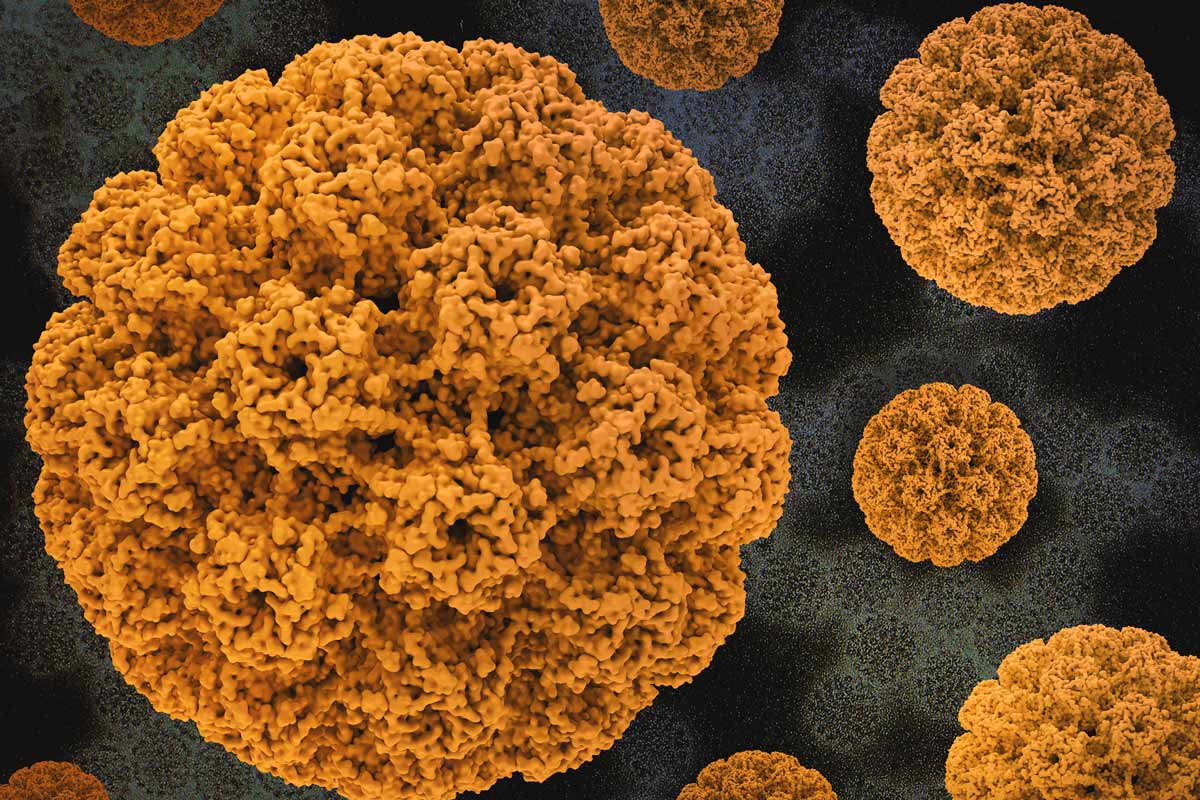

The virus continues to evolve rapidly, leading to different variants

Since the start of the pandemic, the fast-evolving virus was throwing up so many different variants that WHO began labelling them with letters of the Greek alphabet. Since then prominent variants have included Alpha, Beta, Delta and Omicron.

Omicron, a much more contagious variant than the original virus, has spawned several sub-variants. The Omicron sub-variant XBB.1.5 is the most transmissible one so far. A study in the medical journal, Cell, in December 2022, suggested that this sub-variant is better than any other at evading immunity from vaccination or previous infection.

Have you read?

Vaccines prevent severe disease and have been tweaked to deal with Omicron

COVID-19 vaccines are still extremely effective at preventing severe disease and death. However they don’t necessarily stop infection entirely, especially with newer variants that have become better at evading immunity from vaccines and natural infection. What’s more, while vaccination coverage was high in high-income countries for the first vaccine, subsequent booster doses have seen lower uptake.

Omicron caused high rates of infection in late 2021 because the variant was better at evading vaccines than previous variants, however in mid-2022 both Pfizer and Moderna updated their vaccines to offer broader protection, not just against Omicron but other potential variants.

Immunity from recovery from infection also prevents severe disease

A meta-analysis in The Lancet showed that natural infection can confer significant immunity from re-infection and was “high for ancestral, alpha, beta, and delta variants, but was substantially lower for the omicron BA.1 variant”. Protection from past infection was over 88% against severe disease (hospitalisation and death) for all variants, including omicron BA.1.

The pandemic had significant mental health effects

COVID-19 has had significant negative psychological effects, especially on young people and women, according to WHO. In the first year of the pandemic alone global prevalence of anxiety and depression increased by a massive 25%.

WHO cites the “unprecedented stress” from fear of the virus, social isolation and loneliness, suffering from infection, losing loved ones, and financial and economic worries as stressors that have led to a rise in mental health conditions. Among health workers, exhaustion has been a major trigger for suicidal thinking.

The COVID-19 vaccine can temporarily affect menstruation but not fertility

There have been anecdotal reports of the COVID-19 vaccine affecting periods – either by slightly altering the cycle length or making them heavier, which has caused people to wonder whether the vaccine will have any long-lasting impact. The effects have been a temporary blip, say researchers, but they emphasise that there is no evidence that this will affect fertility.

A team at Boston University School of Public Health looked at data from a pregnancy study that follows US and Canadian women aged 21 to 45 years trying to conceive. The study in the American Journal of Epidemiology found that either partner’s vaccination status did not affect their chance of conceiving.

Antiviral treatments are now available, but prevention is still better than the cure

Antiviral treatments such as remdesivir and nirmatrelvir-ritonavir are able to treat COVID-19 infection, though they are mostly only available in middle or high-income countries. They are especially important for people at highest risk of getting seriously ill from COVID-19, such as people with certain types of cancer, those who have had an organ transplant or those with HIV/AIDS.

As with vaccines, equity is important and pilot schemes have been underway since late 2022 to bring antivirals to low-income countries, with an initial donation of 100,000 courses of treatment, to be distributed in nine sub-Saharan African countries and Laos.