Rachael Hore and Emily Loud, Gavi.

In the year 2000, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) set out to reduce global poverty and hunger and to improve health, education, living conditions, environmental sustainability and gender equality. By 2015, there has been remarkable progress towards achieving these goals, prompting United Nations Secretary General, Ban Ki-moon, to claim that they are ‘the most successful anti-poverty movement in history’. However, this has been disputed by many, and significant questions remain around the issue of equity and why some of the world’s most vulnerable children have missed out.

This weekend, following on from the job started by the MDGs, the UN General Assembly will ratify the Sustainable Development Goals for the 2015-30 period. Here we explore some of the broad scepticism levelled at these new goals, and counter it by looking at the contributions of the immunisation community since 2000 and the role these can play in future progress.

1. The goals are too vague, broad and unrealistic

The 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Photo: UN

The goals are broad, but beneath each one are a number of targets which are assessed using agreed indicators. These add up to 17 goals and 169 targets, in contrast to 8 goals and 21 targets established by the MDGs. The new proposals may seem overwhelming, but their greater level of detail could help them to be more effectively adopted as action points. For example, part of goal 3 – to “ensure healthy lives and well-being for all at all ages” – includes a target to ensure access to safe, effective, quality and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all. To help save as many lives as possible, Gavi is aiming to ensure that full childhood immunisation is included as a “tracer” indicator towards this goal, based on a measurement of all vaccines used within national immunisation programmes. This would provide specific, measurable focus for this important area going forward.

2. These goals won’t work for those affected by humanitarian crises

Photo: Artist Frank Viva, via the Art of Saving A Life

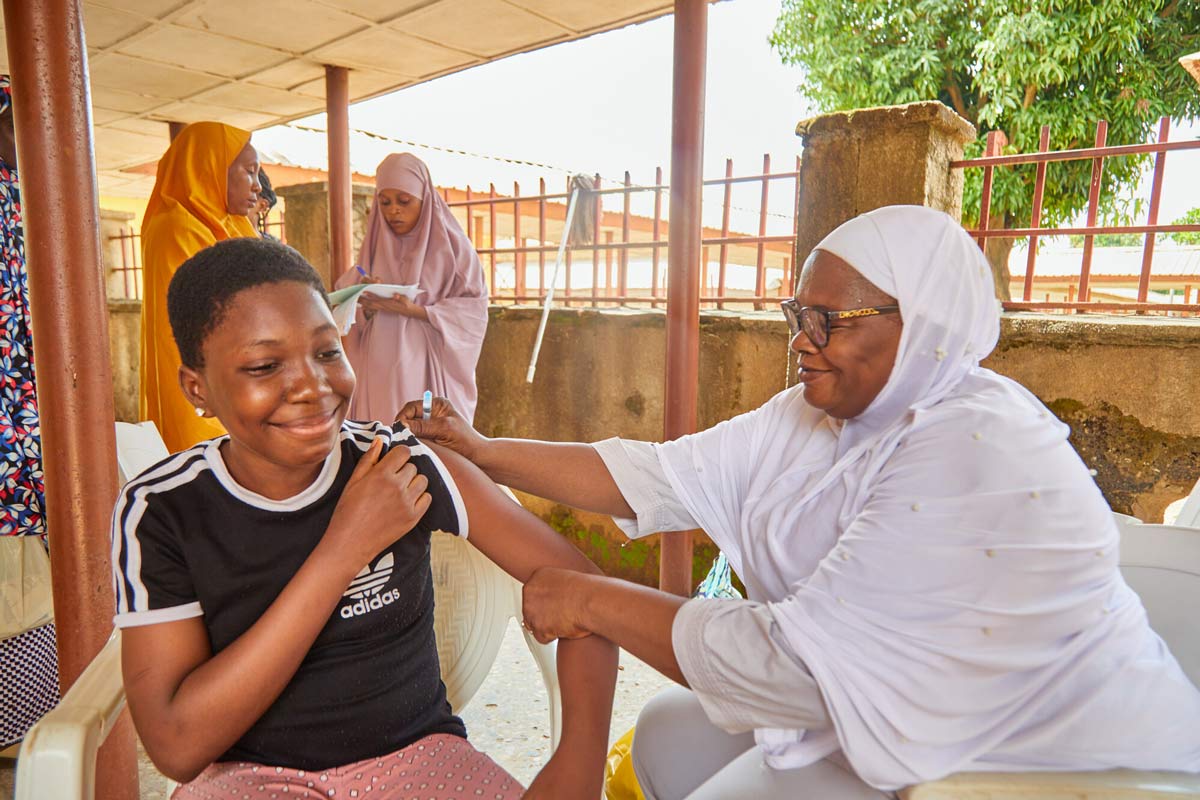

16,000 children under-five still die every day, nearly half of these deaths are in countries affected by humanitarian crises, making it a real challenge to the goals of achieving good health for all. Nevertheless, in the last 15 years, humanitarian organisations have overcome barriers to reach the most vulnerable children with vaccinations in South Sudan, Yemen and Syria. Elsewhere, vaccinators have risked their lives to immunise children in war-zones, negotiating “days of tranquility” with belligerents to allow immunisation to take place.

With a renewed focus on the most vulnerable and hard-to-reach children post-2015, we can be more prepared to help them when disaster strikes. Gavi’s support for a cholera vaccine stockpile is one example of how this can work.

3. The goals target, but don’t involve developing countries enough

Photo: UN

While the MDGs focused on developing countries, the SDGs target a broader audience. The goals offer a more integrated approach to development, including a greater focus on the natural environment and climate. Moreover, the drafting process for the SDGs was far more inclusive, involving more players over a greater length of time, ensuring wider participation for developing countries.

Sustainability should also mean countries building their own success, which national leadership and co-financing of vaccination programmes has already helped to advance. Gavi’s model of co-financing for vaccines creates a sustainable relationship between recipient countries and donors. Over the past 15 years, some countries have ‘graduated’ from Gavi support, meaning that they now self-finance their immunisation programmes. China, which was one of these, is now even a Gavi donor.

4. Targets won’t help further progress in global health and international development

Visualising progress in child mortality over the MDG period. Source: Gates Notes.

While the MDGs may not have been widely discussed among the general public, they provided momentum, funding and guidelines for international development initiatives worldwide. The sustainable development goals can continue this trend, and Gavi is just one example of an organisation that used these development indicators to push for further lifesaving action and funding earlier this year.

Although scepticism surrounding the MDGs and their successors may be warranted, the global vaccine perspective gives a strong indication that broader engagement and greater progress can be achieved. As the UN General Assembly kicks off in New York this week, there is every hope that the global goals agreed there will shape our future for the better.