White Paper

December 2023

Contents

The COVAX Strategic Coordination Office

Disclaimer:

This document published by COVAX partners, including CEPI, Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, UNICEF and WHO. The contents included are the result of a collaborative process managed by the COVAX SCO. The republication or usage of the content of this document of any kind without written permission is prohibited. Please contact press@cepi.net, media@gavi.org, tingram@unicef.org, mediainquiries@who.int with any requests for use.

Share

Background

COVAX was the global, multilateral initiative aimed at making COVID-19 vaccines available equitably to those that needed them. It was also the largest vaccination programme in history, covering 146 countries and delivering ~2 billion doses over three years.

This paper considers the make-up, attributes, successes and challenges of the COVAX Strategic Coordination Office (SCO), one of the key functions of this effort. It has been authored by members of the SCO, informed by a wide range of interviews and feedback undertaken with leaders and operational teams from across the 30+ COVAX workstreams.

COVAX was co-led by the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the World Health Organization (WHO), working in partnership with developed and developing country vaccine manufacturers, the Pan-American Health Organization (PAHO), the World Bank, civil society organisations, funders, and others.

COVAX was an end-to-end partnership with dedicated groups working along the vaccination value chain: from accelerating the development and manufacturing of COVID-19 vaccines to promoting fair and equitable access for every country in the world, assisting countries with rolling out vaccination programmes and strengthening in-country delivery systems.

The COVAX Strategic Coordination Office (SCO) was the cross-partner secretariat that worked across the network of teams and organisations to align leadership, management and operational delivery.

While this paper draws upon experiences gained during the COVID-19 pandemic, it also proposes lessons for future pandemic responses, as well as what might be maintained during intra-pandemic periods, to allow us to be better positioned to a future emergency.

The COVAX Strategic Coordination Office

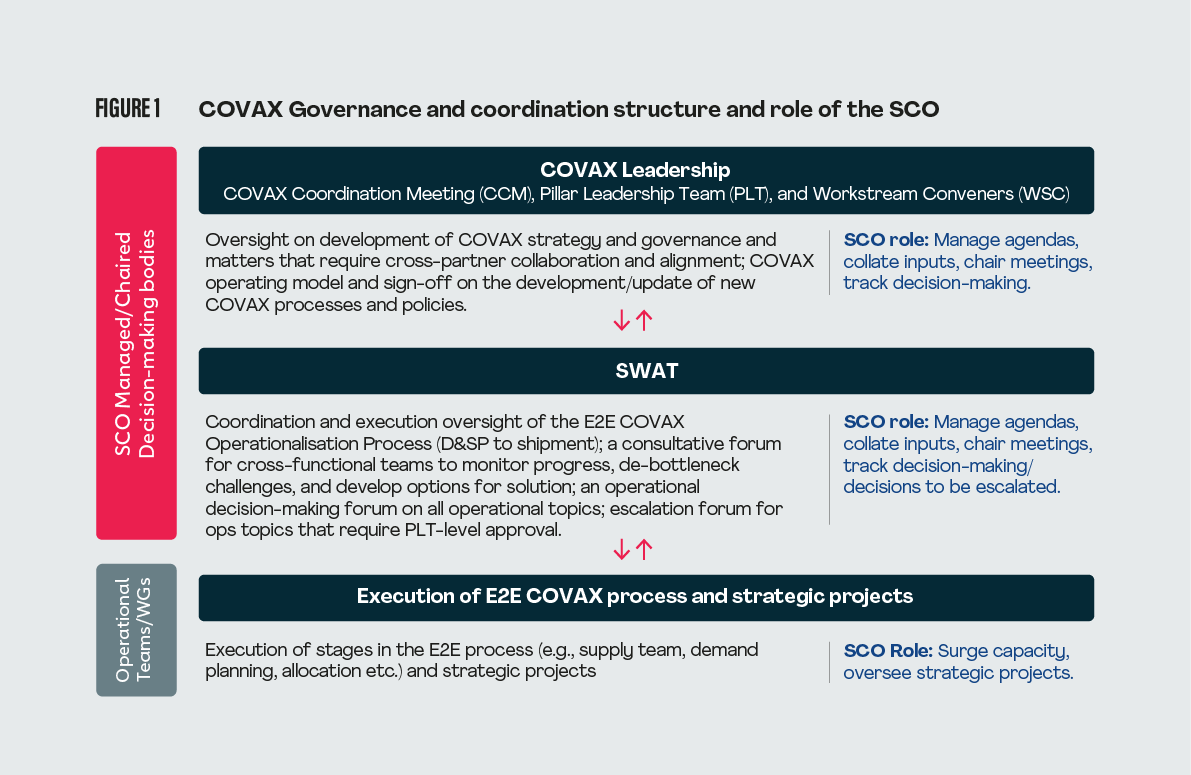

The COVAX SCO had three main capabilities:

Governance and coordination. The COVAX SCO provided the secretariat for COVAX cross-partner decision-making, bringing together senior leaders from each partner organisation. At the peak of the pandemic there were a minimum of four, and often more, cross-partner decision-making meetings each week to align on risks and resolutions and make decisions at pace. In addition, working groups and task forces (e.g. on manufacturing, external communications, resource mobilisation, strategy, etc.) were convened during the course of the pandemic. The SCO managed the agendas, schedule, invitation list, content curation and minutes for all sessions. A member of the SCO also chaired the meetings. Furthermore, the SCO organised quarterly leadership "retreats" once these were made possible by global easing of COVID-19 restrictions.

Operations. The SCO coordinated all COVAX operations, working closely with workstream leads across the vaccines value chain. As chair of the main operational meeting, known as SWAT, the SCO played an important role as the "glue" that kept the operational process functioning, and driving actions to overcome problems. During COVAX, the SCO was also asked to surge into operational positions outside of the core scope to provide project management or other skills. The workstreams that SCO members worked on included product management, donations, demand management, allocations, manufacturing and data management.

Strategic projects. The SCO oversaw time-limited, strategic projects. These included coordinating the COVAX Strategy and Budget for 2021–22, writing the COVAX Structures and Principles document, developing the 2023 COVAX Operational Plan, determining the Worst Case Scenario Preparedness Plan and coordinating the COVAX close-down.

Note: Although the core scope and mandate of the SCO remained reasonably stable throughout COVAX, the actual activity of the team was constantly evolving to meet the shifting needs of the pandemic response. Looking back, the SCO updated its approach and team roles approximately every three months. This ability to "evolve on the move" was a core attribute that allowed the SCO to remain fit for purpose as circumstances changed.

Successes and challenges of coordination during COVAX

Neutrality. The COVAX SCO comprised individuals drawn from the four COVAX partners. Representation from each partner was crucial in making this central function a "team for all". During onboarding, team members were asked to set aside organisational affiliations and act with a "One COVAX" mindset. This helped the SCO foster trust across all partners, allowing it to be an honest broker, even at times of tension or disagreement.

"What we as senior leaders often do if there are bumps, is we talk within our organisation. This is because we don't have a neutral person to raise our grievance with. The SCO neutrality provided a key role."

SCO members did at times face challenges to this approach. First, there were times when there was pressure to advocate for their own organisation’s position. Equally, there were times when it was suggested they were acting in their organisation’s interest. It is likely this tension will always occur in such constructs – particularly where others are in roles that require a less neutral mindset. However, the strong focus on the "One COVAX" mindset from the onset, and the widely accepted principle that the SCO is a "neutral" team, helped to mitigate these challenges. Further, that criticism was received in both directions indicates that the right balance between the two was broadly maintained.

Convene, coordinate, collaborate. Not tell, direct or command. COVAX was not a legal entity. It had no formal board and no formal decision-making powers. There was never any collective COVAX budget that was managed through a central fund and function. Instead, formal decision-making remained within the structures (Boards, line management) of each organisation. Despite this, COVAX fostered enough trust so that the cross-partner forums that were established took collective decisions that each organisation then felt accountable to enact. Working within this construct, the SCO did not have any mandate to task, tell or direct. However, it played a crucial role convening, coordinating and driving collaboration.

"The job and work to bring everyone together and on the same page, to get people to walk in the same direction, at the same pace, has been amazing. The SCO has been crucial to the functioning of COVAX."

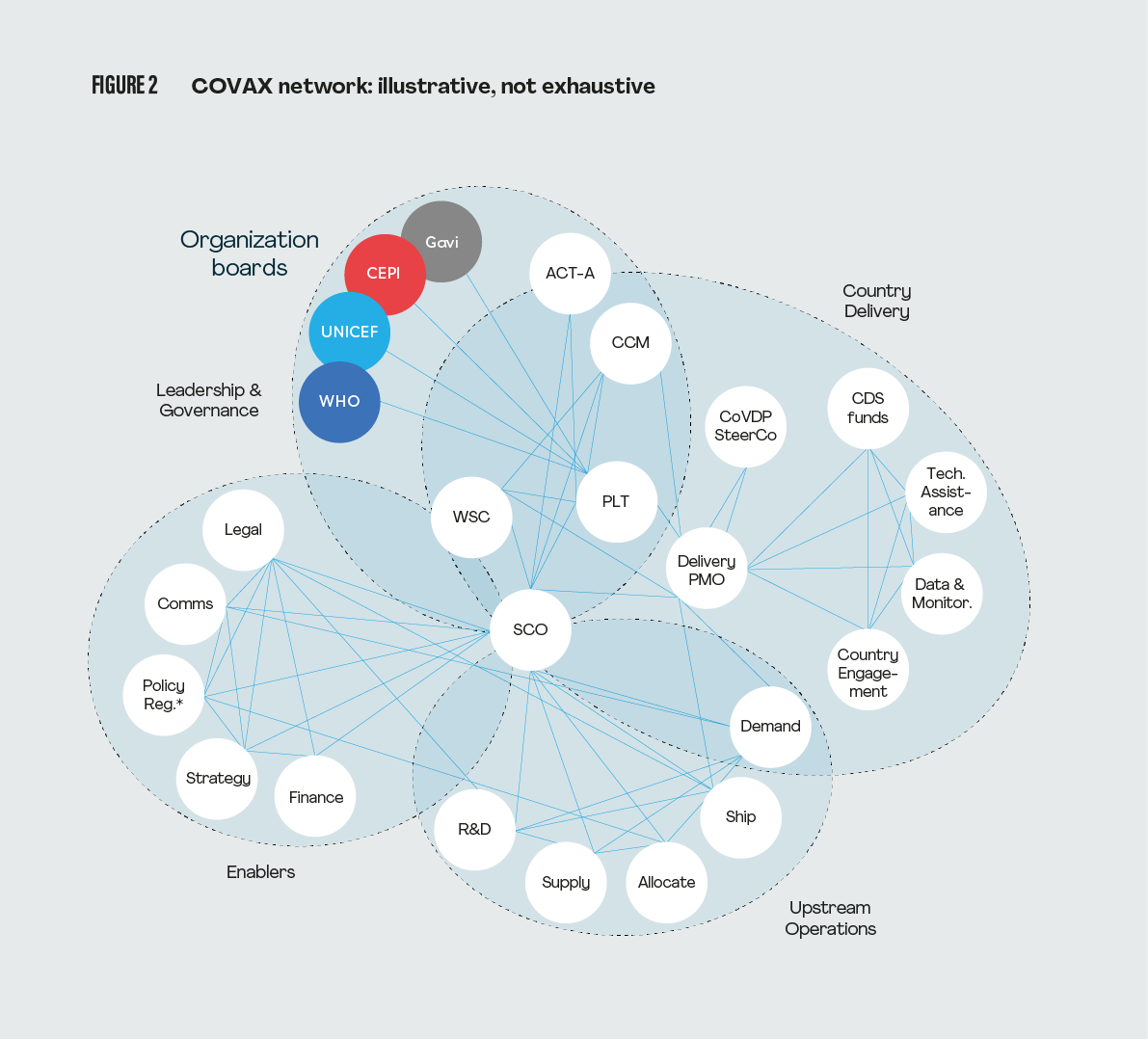

Within this model, achieving the pace of progress required during an emergency can be a challenge. A classic, hierarchical management model can establish command and control approaches that quickly direct teams to deliver outputs. COVAX was a networked structure (see Exhibit 2), and therefore delivery had to be achieved through collaborative approaches, given there was no hierarchy among the four equal partners.

The importance of influence, diplomacy, and compromise in this model was much more heightened. Specifically, the SCO was the connector of disparate nodes, investing upfront to try and reach consensus, then convening decision-makers to make collective decisions. This allowed meetings with large agendas to progress efficiently and meant most issues were resolved before large online meetings, where there can be pressure to hold a position.

Balanced skill set and flexibility. In addition to the importance of coordination and collaboration in a network-like structure, the skill sets of the SCO members played an essential role for facilitating cross-cutting problem-solving in an efficient way. Through their diverse backgrounds, the SCO team was able to identify pain points and issues and escalated these to the various governance bodies as needed. The diverse skill sets among the team and the SCO’s connecting position in both operational and strategic discussions also placed the team in a position to not only identify challenges across the COVAX workstreams, but also to provide support where needed. This resulted in the SCO providing surge support across the COVAX value chain during times of necessity. The team’s high level of experience and agility provided them with the resilience and flexibility to quickly assume this operational responsibility when and as needed.

"One learning is that this type of structure is a ‘must replicate’ whenever you have different partnerships. […]. Having a sizeable coordination function, but that is small enough to be agile, and leveraging the knowledge and power of institutions is critical."

The evolving nature of the pandemic necessitated a continual review and update of the focus of COVAX and the SCO. To ensure adaptability and to maintain a fit-for-purpose team, the SCO conducted quarterly reviews of the team structure along with their roles and responsibilities. This quarterly exercise provided the team with the means to reflect effectively on the challenges and successes of the preceding quarter, and efficiently adjust and retool to acclimate to the dynamic needs of COVAX.

Looking across the value chain. Apart from leadership, most teams were positioned at particular points in the vaccines value chain. The SCO was unique in working across the value chain up to arrival in country. It was key that the SCO had their ‘finger on the pulse’ of COVAX throughout its various phases. From this position, the SCO was able to identify and help solve hand-off challenges, connect different teams and have an early view on potential issues before they became too large. The SCO’s view of the end-to-end activities allowed for visibility of the interconnected picture of COVAX, allowing the SCO to pinpoint and escalate any interdependent challenges that needed to be resolved collaboratively or discussed in a higher forum.

"The SCO kept COVAX operations on track and managed to create a process for the partners to interact. COVAX has been pretty remarkable in terms of day-to-day integration, which is largely attributable to the work of the SCO."

Open by design. By having a "One COVAX" mindset, the SCO helped to drive transparency between organisations. In other settings, organisations can be reluctant to share draft versions of documents before they have progressed through the (often many) layers of internal review and sign-off. By nature, many COVAX activities involved inputs from teams across several partners. The result was an "open by design" mentality. The SCO did not solely create this, but by proactively behaving in this way, played an important role in setting the tone for how COVAX teams worked together.

"Non-intrusive and helpful. It is not always the case that you have this kind of set-up. It was neutral and drove things along, linking everyone up. It helped overcome egos and institutional boundaries."

Building the right culture. That the SCO established the above characteristics helped to create a team that was efficient, high-performing and widely trusted. However, these attributes did not develop organically. They were pre-identified during mobilisation and reiterated throughout the pandemic, with new joiners receiving a specific briefing covering neutrality, transparency; being told: "Convene, don’t direct."

Resourcing. Throughout the life cycle of the SCO, recruitment proved challenging. The absence of a team budget and the resulting reliance on agencies’ unaligned funding cycles created recruitment delays. This lack of reliability in the SCO resourcing model led to many short-term contracts, resulting in a lack of continuity, prolonged lead times for recruitment and upskilling, and a sense of frustration within the team due to a lack of uncertainty in the future of their roles.

Looking forward

Section 2 puts forward a set of principles and a potential model for how a similar coordination function might be prepared for and established for a future emergency.

Principles of effective coordination in a global health crisis

- Clear mandate and scope: establish a function that has a clear mandate to drive and coordinate activities across all partner organisations.

- "Skin in the game" through multi-agency staffing: establish a function that is resourced with delegates from all partner organisations, helping to build trust by giving each partner a dedicated seat at the coordination table

- No egos: be a voice for all partners through neutrality and transparency. While staffing is multi-agency, the philosophy of the team is to support the greater objective of the partnership, instead of partner-specific agendas. Operate under and help to drive an "open by design" approach to the development and execution of all strategic planning and operational activity.

- Skills, skills, skills: resource a team of problem-solvers, listeners, relationship-builders, prioritisers, and strong communicators. In a network delivery model, a coordination unit with such skill sets drives forward outcomes and decisions not by telling or commanding, but finding common ground through convening, collaborating and joined-up coordination.

- Remain agile – horizontally and vertically: as the course of a crisis evolves, so the coordination unit must do the same. Team members must be agile and comfortable with ambiguity, and the operating model should be ready to adjust to the changing needs of the crisis. Develop strong links to regional, national and other global coordination activities to maximise the network effect and avoid silos.

Preparing for future health emergencies

While partners frequently work closely together on aspects of outbreaks1, the COVID-19 pandemic was the first time agencies had come together to coordinate a full-scale, pandemic-level response across the full vaccines value chain. The fact that the COVAX Strategic Coordination Office (SCO) was not fully established until April 2021 reflects that it takes time to put such a model in place. Further, establishing such a function from scratch during an emergency presented many resourcing, scoping and process challenges.

Steps should be taken to prepare before time, so that organisations can more quickly scale up this capability as a crisis begins. Below are outlined options for how both an intra- and future crisis coordination function might be constituted.

For all options outlined below, having a clear scope and mandate for the group is essential, as well as the governance mechanisms for each partner to ensure effective decision-making and the capability to quickly pivot between interpandemic and emergency response, when required.

Between emergencies: intra-crisis coordination

Maintain a small number of cross-partner resources in an informal or formal arrangement: the team is tasked with epidemic and pandemic-scale vaccines emergency planning. These resources could then establish and support a working group of wider stakeholders. Examples of types of potential intra-crisis coordination team models include:

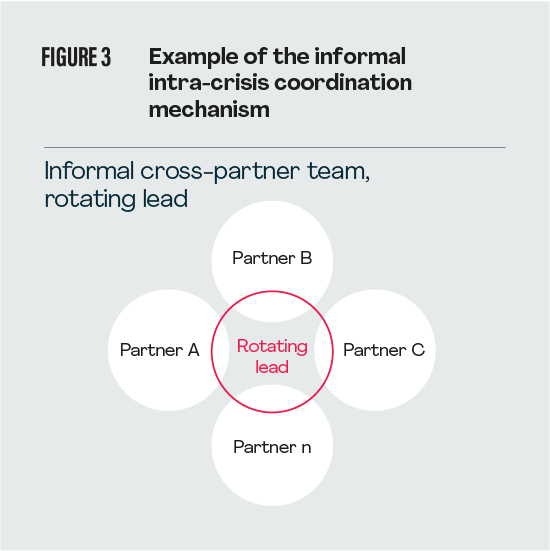

- Informal: people based in each organisation who collaborate in the running of a working group, development of a workplan and realisation of agreed outputs. Such people should have dedicated time set aside from their home organisation. This model allows for more flexibility in the intra-crisis time period and requires fewer formal arrangements to be put in place. However, there is a risk of competing internal initiatives taking priority for each organisation, plus it may take such a group longer to make progress versus a formally constituted team.

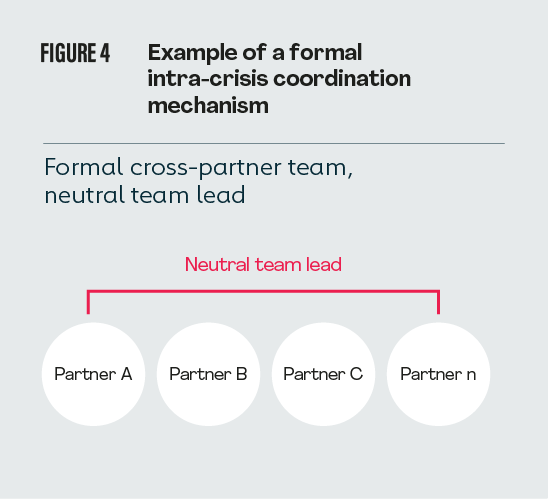

- Formal: A stand-alone cross-partner team could be established that comprises team members partially or fully seconded from their home organisations. Team members could report into a neutral lead. Partners could rotate nominating the lead, who has a brief of neutrality, representing the partnership as a whole. A stand-alone team guarantees dedicated time and capacity from each organisation, and quick scale-up in the event of a crisis. This would have a higher resourcing cost across the organisations and require more formal agreements to be put in place.

- Informal: people based in each organisation who collaborate in the running of a working group, development of a workplan and realisation of agreed outputs. Such people should have dedicated time set aside from their home organisation. This model allows for more flexibility in the intra-crisis time period and requires fewer formal arrangements to be put in place. However, there is a risk of competing internal initiatives taking priority for each organisation, plus it may take such a group longer to make progress versus a formally constituted team.

- Develop and manage a workplan of practical solutions: this would include building upon the lessons from COVID-19 to help organisations be better prepared for a future emergency.

- Develop a surge plan with triggers for how to ramp up as a crisis escalates: this would include:

- When to establish a formal coordination unit; and

- When to mobilise more coordination resources and how (finance, talent pool).

- Establish links to wider counter-measures and pandemic preparedness functions: vaccines are just one tool when fighting against outbreaks of epidemic and pandemic scale. It is therefore crucial that any vaccines coordination, either before or during a crisis, is done in concert with areas such as therapeutics and diagnostics.

During emergencies: coordination in a crisis

- Establish and scale up a formal coordination unit: the ability to scale the coordination team at pace is key, as this team will be the "mortar between the bricks" of the emergency response. Ideally an intra-crisis coordination mechanism would be in place with resources already primed to jump-start crisis coordination. Either way, to scale quickly, the following should be in place:

- Access to funding for short-term, potentially external support and other surge support as needed; and

- An agreed mechanism to recruit at pace to build a crisis coordination team, including using consultant contracts as needed while onboarding staff contracts/secondees.

- Resource appropriately with regular reviews:

- Considerations of the team’s skill set: problem-solving and stakeholder management were at the heart of the SCO, and are key skills required in a future team. In addition, an analytical mindset as well as the ability to be agile and work at pace are also key in a crisis to enable quick decision-making. Noting that the team is ideally staffed with contributions from each partner, having an understanding of the ecosystem is helpful in order to leverage the knowledge and power of the institutions. Many key skills can be found in those with a background in strategy consultancy and/or project management.

- Considerations for the lead: in additional to the skill sets required of the overall team, the lead requires special consideration. Given the network structure of a cross-partner coordination, strong stakeholder engagement skills with a focus on influencing is key for the lead. Additionally, a background in strategy, project management office (PMO) and change management would be helpful given the cross-cutting initiatives and frequent pace and scale of change. Finally, while in intra-pandemic times a "rotating-lead" model was judged an option, during the crisis itself this position should be resourced by a single person, asked to act neutrally, no matter which agency contracts them.

- Regular reviews: due to the changing nature of emergencies, regularly reviewing the coordination mechanism’s operating model and staffing to scale up/down as needed is critical for the efficient and effective functioning of the team.

- Establish clear scope and mandate: consider the needs of the emergency, in particular with respect to governance, operations, any special projects as well as any key enabling functions that would fall under the scope of the coordination mechanism (e.g. data visualisation/reporting, communications). Any crisis of this scale will also happen at global, regional and national level simultaneously, so clarity on what is being coordinated at which level is important.

Conclusions

It is likely that the next pandemic-scale health emergency will not follow the same form as COVID-19. Different circumstances will require agility in the set-up and running of a response capability – for example, the role vaccines play may be different (e.g. transmission-blocking or not) and the timing of vaccine availability is likely to change.

However, whatever the nature of the outbreak, the benefits of a pre-planned and quickly scalable coordination capability will be significant. Working cross-organisation and with people at regional and country levels, this capability can play a key role in the hopefully speedy tackling of the outbreak – reducing its impact on people’s health and countries’ economies.

This article focuses on the experiences from COVID-19 and future coordination during a public health emergency. However, it is suggested that the principles described for effective crisis management within a network – coordinate not dictate, open by design, remain agile – could be helpful for similar activities in related fields.

Thank you

The work of the SCO would not have been possible without the commitment of many talented people:

- Lieven van der Veken, Bart Van de Vyver, Anouk Petersen and team, who set up the first version of the SCO;

- Julika Erfurt, who took the helm in April 2021 and led until COVAX closed in December 2023;

- Sachin Bhardwaj, Ozan Akturan, Saira George-Carballo, Annamarie Candler, Violeta Perez Nueno, Lama Gaafar, David Humphries, Catherine Clary and Levke Kooistra as successive Governance and Strategy Leads, and their teams;

- Benedict Millinchip, Jacqueline von Gottberg, Roshni Best, Kira Skolas, Oyeronke Oyebanji, and Kelly Simpson who coordinated all aspects of day-to-day COVAX operations;

- Shellee Taylor, as Data and Analytics Lead; and

- Jonathan Howard-Brand, Diana Khromova, Hannah Frame, Rachel Larson, Mohammed Badawy and Conor Eastop as Product Managers.

The findings of this paper are with many thanks to the COVAX leadership and operational teams for their insights during interviews for this paper and input throughout COVAX:

COVAX Leadership: Richard Hatchett, Seth Berkley, Soumya Swaminathan, Bruce Aylward, Etleva Kadilli, Ted Chaiban, Melanie Saville, Aurélia Nguyen, Derrick Sim, Kate O’Brien, Andrew Jones, Richard Mihigo, Ann Lindstrand and Benjamin Schreiber

COVAX Chief of Staff: CEPI: Joseph Simmonds-Issler, Kristine Rose, Claire Willman; Gavi: Hannah Burris, Alex Beecher; UNICEF: Tara Prasad; WHO: Catherine Mullholland, Jennifer Barragan, Stephanie Shendale, Brian Riley; and CoVDP: Sona Bari, Nisha Schumann

COVAX Operations: The SWAT leads and many, many passionate and committed teams across the 30+ COVAX workstreams

References

1. See the Measles and Rubella Partnership and the International Coordinating Group (ICG) on Vaccine Provision