ZIP: a new way to get vaccines to zero-dose children in some of the world’s toughest regions

With the launch of the Zero-Dose Immunization Programme, Gavi and a web of expert partners are poised to bring health care to children in some of the world’s most precarious frontier-zones.

- 21 June 2022

- 6 min read

- by Gavi Staff

Millions of children in fragile parts of the Sahel and the Horn of Africa remain functionally invisible to health systems, missing out on life-saving vaccines as a consequence. In a bid to help governments fix that, Gavi is launching a novel kind of partnership, a kind of immunisation super-league called ZIP, or the Zero-Dose Immunization Programme.

“Often in these countries there are populations moving across porous borders because they are nomadic by nature, or they have been displaced by conflict or other natural disasters such as flooding. These populations are thus often untraceable and untrackable by governments.”

Over the next two and a half years, two consortia of organisations with deep experience of the operationally-complex contexts in the region will put US$ 100 million to work to find and serve these missing millions.

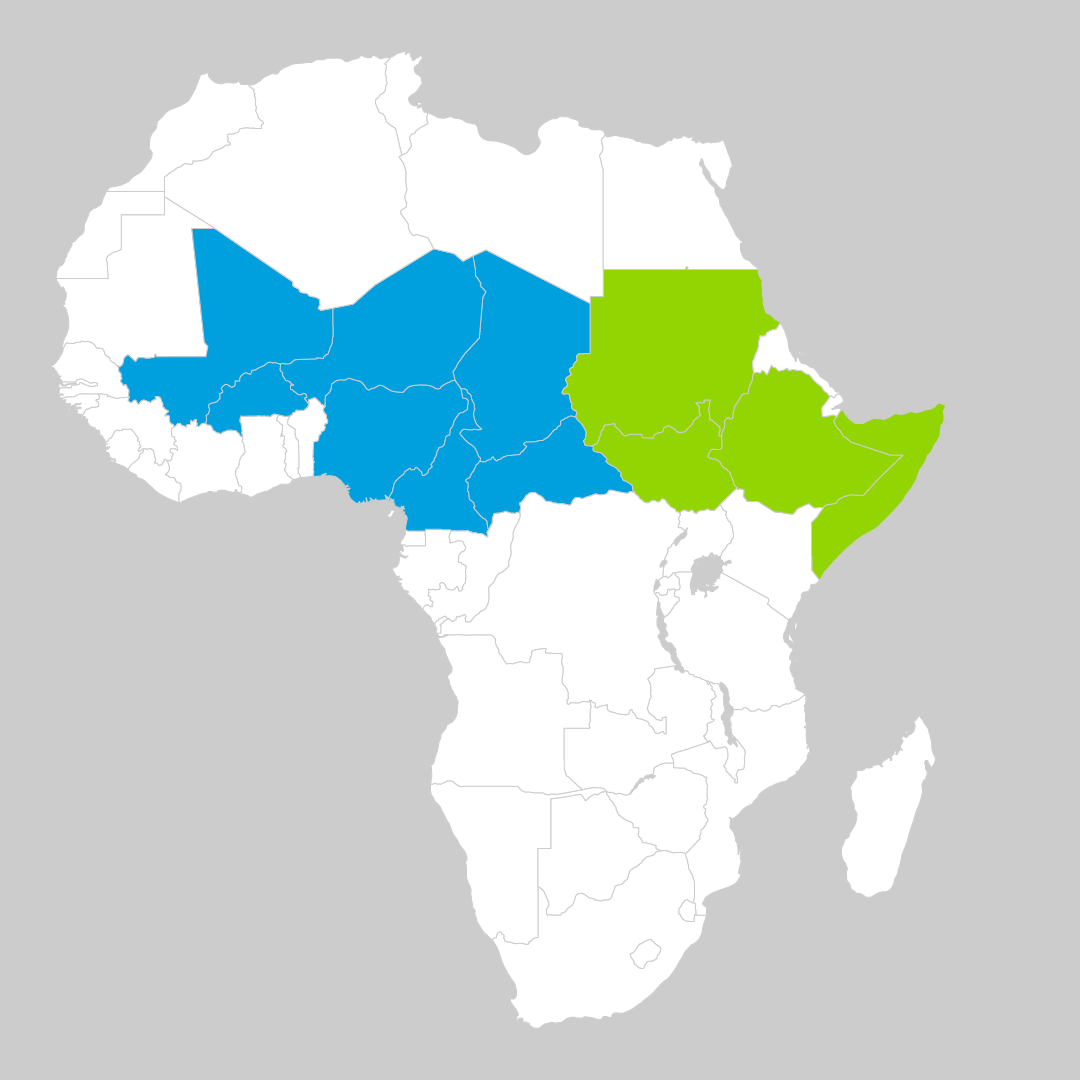

Countries served by Gavi’s new Zero-Dose Immunization Programme

In the Sahel region, World Vision will head up a consortium of organisations including the African Christian Health Association Platform (ACHAP), Food for the Hungry, CORE Group and other local partners to shine a light on immunisation blind spots across Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Central African Republic (CAR), Chad, Niger, Nigeria and Mali.

In the Horn of Africa, International Rescue Committee (IRC) will lead a network of partners including Acasus, Flowminder, IOM, ThinkPlace and local partners, to reach vulnerable zero-dose populations in Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan and Sudan.

Vaccination blind spots

Over the last 20 years, immunisation access in lower-income countries has expanded so energetically that in many places, childhood vaccines now represent the forward frontier of health care. Vaccines are now routine even among people with few other linkages to the organs of public protection. In many isolated communities the immunisation healthcare worker with their blue cooler box of vaccine vials is a familiar representative of an otherwise still-remote health care system.

But an estimated 12.4 million children in lower-income countries remain absent from this picture. And they’re at urgent risk: this fragmented global cohort of the missed-out and unprotected – known as “zero-dose children”, a reference to the fact they haven’t received a single dose of the most basic vaccines – accounts for half of the children who die before they reach age five.

Some four million or more zero-dose children live across 11 countries clustered in the Sahel and the Horn of Africa. Here, explains Amy LaTrielle, Gavi’s Director of Fragile and Conflict Countries, the access gap often comes down to a mismatch between maps drawn by diplomacy and the lives lived by people on the national margins.

“Often in these countries there are populations moving across porous borders because they are nomadic by nature, or they have been displaced by conflict or other natural disasters such as flooding. These populations are thus often untraceable and untrackable by governments,” says LaTrielle. “We know many zero-dose children are found in these communities.”

As country health systems are necessarily contained within territorial lines, Gavi’s tried-and-tested way of working with governments through a one-country approach would have been an imperfect vehicle for this frontier terrain.

Have you read?

Enter ZIP

“We were trying to mitigate for the inability to reach populations moving across borders by designing a regional project,” says LaTrielle. But regional reach couldn’t come at the cost of highly localised, specific knowledge. In the IRC and World Vision-led consortiums, Gavi found partners “with both depth and breadth of experience”, LaTrielle adds.

The IRC alone has more than 30 years of experience negotiating humanitarian access in the Horn of Africa, and “expertise at delivering services in volatile operating environments while harnessing learning from real-time data to adapt programming”, according to Shiferaw Demissie, Project Director for the Gavi REACH Consortium at the IRC.

But it isn’t on its own. It has plenty of back-up: each consortium partner in the Horn has, according to Demissie, “trusted community relationships and close partnership with local and government authorities,” and specialist experience. IOM, for example, has 16 offices dotted across Ethiopia, South Sudan and Sudan, and “deep expertise in mapping and tracking displaced populations”.

World Vision and its partners likewise have both a strong presence and experience in programming across the seven target countries in the Sahel region. The density of partners’ footprints across each region is key, because local contexts vary widely, and will present diverse challenges. In an email, a World Vision spokesperson wrote, “Ongoing unpredictability in the security situations (i.e. intercommunal fighting, cattle rustling, conflicts between government forces and non-state actors, etc) can limit access to health services, risk staff and community safety and drive population displacement within and between target countries.”

“These are realities we as a consortium will have to navigate, anticipate and plan towards mitigating to maintain immunization and integrated services. Here is where partnering with local civil society and local organizations is critical,” World Vision continued.

Demissie anticipates that some communities in the Horn of Africa will face access challenges ranging from infrastructural insufficiency, to blockades imposed by insurgent groups, to displacement caused by climate change. In some areas, she says, community trust-building might require focus, while in others the priority may be making sure that religious or nomadic leaders understand the importance of immunisation.

Getting access right, then, requires both proximity and sensitivity. “We need to understand from communities, in their own language, what their barriers to access are. Why are there zero-dose children here? We know that the gender of the caregiver plays a role in the ability to access health services. Additional barriers include the health facility being too far away for easy access, that the hours of operation, or even days create a barrier or that the caregiver doesn’t feel safe to travel the distance. But those answers come from the communities themselves,” says LaTrielle.

Gender dynamics need to be understood and factored into design. And it’s vital, she adds, that the work on the ground is done by community members – not workers from the capital, and certainly not parachuted-in international staff. “It’s incumbent upon us to have a community-driven approach, complemented by the expertise of the consortium members to design outreach that optimally serves the zero-dose children.”

Reaching kids where, and how, they are

Like zero-dose communities all over the world, the populations served by the ZIP consortia in the Sahel and in the Horn of Africa are likely to be missing more than vaccines. Research shows that two-thirds of zero-dose kids live in very poor households facing deprivations including lack of access to reproductive health services, water and good sanitation.

Here, again, immunisation is likely to be one of the first services to connect with a given community. It shouldn’t be the last.

“ZIP project success hinges on ensuring that zero-dose children receive a full suite of life-saving immunisations, not just an initial dose,” LaTrielle says. “And we need to ensure integration of services is at the heart of our approach by making sure our funding for outreach is complementing other projects.”

More than immunising children, the Demissie says, the consortium intends to “extend the reach of healthcare systems to ensure that these children are accounted for.”

The work “is not going to be narrowly focused on getting the vaccines into children,” says World Vision of the mission in the Sahel, “but also addressing the broader community and health system causes as to why countries still have zero dose children – and how services can be resilient despite the barriers of reaching zero-dose children and communities with other key essential services.”

The aim is equity. The aim, in other words, is nothing short of transformational.