Encouraging vaccination in Nairobi: “If we work on awareness and motivation, we are good to go”

Pamela Anyango is on a mission to boost vaccine coverage in Dandora, Kenya, home to a garbage dump that has been labelled the ‘cradle of the next pandemic’.

- 28 May 2021

- 6 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

Dandora in eastern Nairobi is best known as the site of the Kenyan capital’s largest garbage dump: 30 acres of refuse, picked through for survival by people, stray livestock and a thriving population of marabou storks. A 2017 article in the Journal Sentinel called the Dandora dump “a Petri dish for the creation of new threats to human health,” and imagined it as, conceivably, the cradle of the next pandemic. But even amid that next pandemic, Pamela Anyango, a local Community Health Assistant, worries above all about age-old and regrettably still-familiar health threats, like measles.

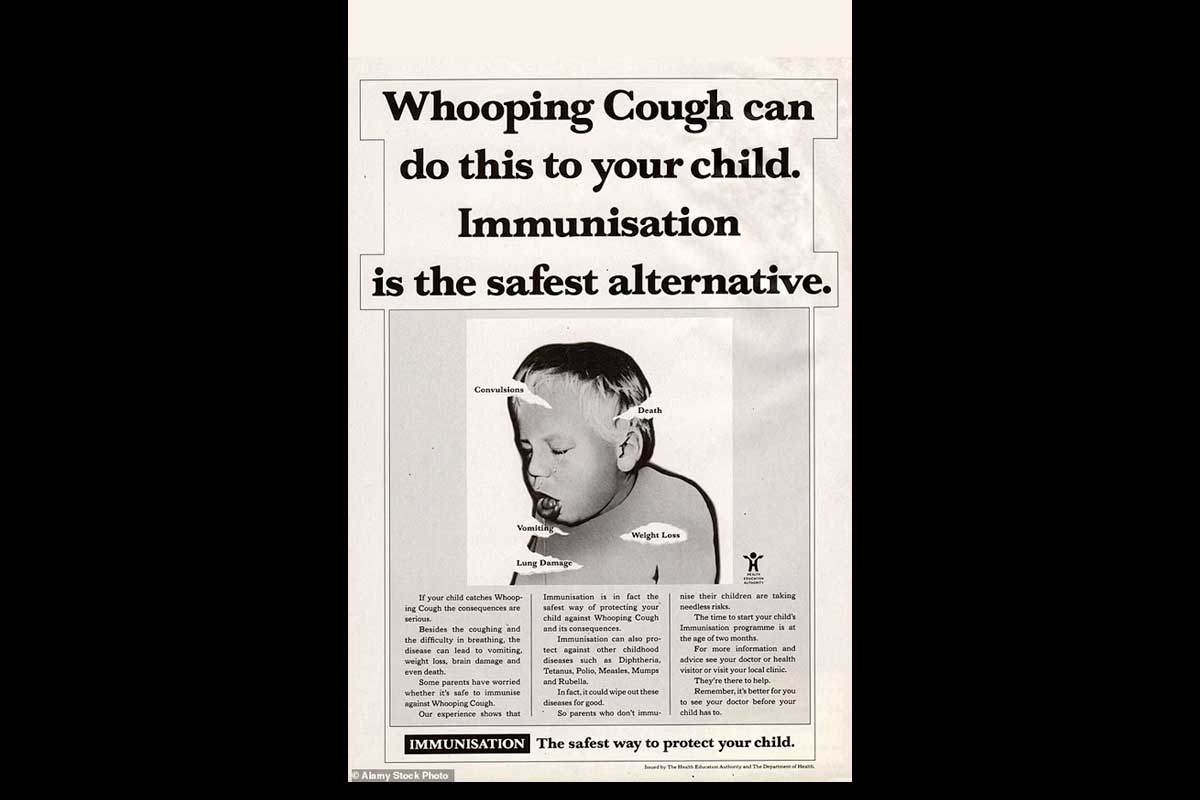

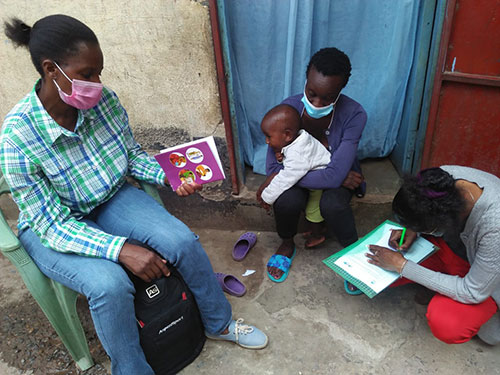

Measles was on Anyango’s mind one sunny March day as she sat down on a tyre outside a house made of corrugated aluminium to speak to the mother of a so-called “vaccine defaulter”. Her enquiries were phrased gently. Why was it that baby Caleb had fallen behind on his routine shots? Caleb – a stern toddler, at that moment busy frowning at an elastic band stretched between his two hands – sat on the lap of his mother, a young woman named Agnes Opetu. Opetu’s eyes slid away to the ground as she explained. Caleb was vaccinated as an infant, but her husband had taken the children upcountry, and their immunisation booklets had been forgotten. The kids missed appointments, and soon, Opetu felt uncomfortable taking them to the health centre. “I thought that the nurses would scold me,” she said. “I feared they would insult me.”

In Dandora, vaccination coverage among infants is high, but it drops off as they are due their 9-month vaccines.

Anyango, a 41-year-old community healthcare veteran based at Dandora Health Clinic for the past six years, says that the anticipation of disrespectful handling is the concern she encounters most frequently when she reaches out to the mothers of under-vaccinated children. “You meet a group of mothers, and the first thing that they are likely to mention is the fear of being insulted,” she says. This isn’t vaccine hesitancy, she clarifies – vaccination itself is well-accepted. Rather, it’s a culturally engrained anxiety about encounters with the institutions of public health.

“It is something they’ve lived with for a long time,” Anyango says. “The older generations are passing the same fear to those who are there now.” If one person is wronged, the information spreads from person to person “until the entire community lives with fear. That’s the major, major challenge we are facing as health workers.”

|

|

|

|

Credit: Pamela Anyango

“Surely, Mama Caleb!” Anyango exclaimed, warmly reassuring Agnes Opetu. “No no! Nowadays there are no insults.” Opetu smiled a little, self-consciously patting her child. Anyango went on: “and please tell the other mothers that if they fear being insulted upon arriving at the health centre, let them ask where the community office is.” Let them report the rude worker by name, she pledged, “and see us deal with that.” Caleb aimed his elastic band like a sling-shot. Opetu pinched a shred of fluff from his scalp.

“Let me ask you,” Anyango continued, “did you ever see a child suffering measles infection?” There was fresh cause for alarm: that very month, a small outbreak of the deadly illness had emerged in Dandora. The news had surfaced via the network of CHWs, or Community Health Workers, trained grassroots volunteers who are essential to Anyango’s projects. The surveillance team moved quickly, she says, and the infections – numbering about six, by then – were taken in hand. One child’s illness was severe, but with care, she recovered.

Have you read?

In fact, Opetu answered, she suspected Caleb may have had measles himself. She described rashes all over his body, pulling the child across her lap and tugging down his trousers to indicate marks on his bottom and legs. Anyango responded with small noises of curiosity and concern before explaining that measles can leave a child blind or deaf, “and sometimes, they may not make it”. “I want to request you to bring Caleb to the health centre to get immunised against measles,” she said.

Anyango is a mother of four herself, which makes it easier to connect with the women she encounters on her rounds in the community. “I reflect, when I get a child that is not vaccinated, what if I’m in the shoes of this mother? Most of the time, I really, really feel for these kids, and I really feel for their mother. I fail to judge them.”

That empathy is called upon regularly enough. In Dandora, vaccination coverage among infants is high, but it drops off as they are due their 9-month vaccines. “The ones that come at the one-and-a-half-year mark are the ones that are majorly affected [by defaulting], and coverage is very low.” The pattern has roots in ignorance – women don’t quite understand the life-saving importance of measles vaccination. Their kids, now toddlers, have lost the fragility of early infancy, and for some women it’s time to prioritise “looking for money to fend for the family.” Under such conditions, the threat of an indignity – of insult at the clinic – is deterrent enough. “If we work on their awareness and motivation, we are good to go,” says Anyango, with the energy of a professional optimist.

Over six years, her work has generally become a little easier as she has slowly built the community’s trust – “getting any health information from them becomes easy,” she says. But coronavirus has been a stumbling block. Immunisation rates dipped as families avoided the health centre, and amid acute financial instability, the rate of attrition among the voluntary CHWs has been high. But in any year, Nairobi, like most major urban centres, sees a lot of comings and goings. There are always new people, like Agnes Opetu, to meet and build relationships with.

The day after her first meeting with Anyango, Opetu arrived at Dandara Health Clinic with Caleb and her older boy, an under-vaccinated four-year-old. As Anyango looked on – filming the proceedings on her mobile phone – both children received a first dose of measles-rubella vaccine. “Good boy!” murmured Nurse Grace Ndiritu as she withdrew her needle. She chatted cheerfully with Opetu, who laughed a bright laugh and cuddled Caleb in her lap.

There are many challenges in the job, says Anyango, but there are also moments of profound satisfaction. “As a person I feel that is a reward enough to make me wake up every morning and go to the community,” she says.