What is Gavi’s role in stopping the COVID-19 pandemic?

On the most recent issue of The Bio Report podcast, Gavi's Aurélia Nguyen discusses COVID-19 vaccine development, the role of the Vaccine Alliance in stopping the pandemic, and shares lessons learned from the 2014 Ebola outbreak that may prove useful to countering coronavirus.

- 25 March 2020

- 13 min read

- by Gavi Staff

The Bio Report podcast, hosted by award-winning journalist Daniel Levine, focuses on the intersection of biotechnology with business, science, and policy.

Aurélia Nguyen is Managing Director, Vaccines & Sustainability at Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance

Full transcript

Daniel Levine: The COVID-19 pandemic is threatening to stress healthcare systems throughout the world and it’s making the development of a vaccine an important part of a strategy to arrest the virus. Though clinical trials for a vaccine are underway, creating one alone will not be enough. If those efforts are successful, there will be challenges ahead with manufacturing, distributing and providing equitable access throughout the world.

We spoke to Aurélia Nguyen, Managing Director for Vaccines and Sustainability for the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations about the COVID-19 outbreak, how it may be playing out in different parts of the world and what was learned from Gavi’s involvement in previous efforts to develop an Ebola vaccine. Aurélia, thanks for joining us.

Aurélia Nguyen: Thank you for having me join you today.

Daniel Levine: We’re going to talk about Gavi efforts to develop a COVID-19 vaccine and how the pandemic is impacting different parts of the world. As someone who is involved in global health and has been involved in responding to past outbreaks, perhaps you could begin with some perspective on the current pandemic; how does it compare to what we’ve seen in the past?

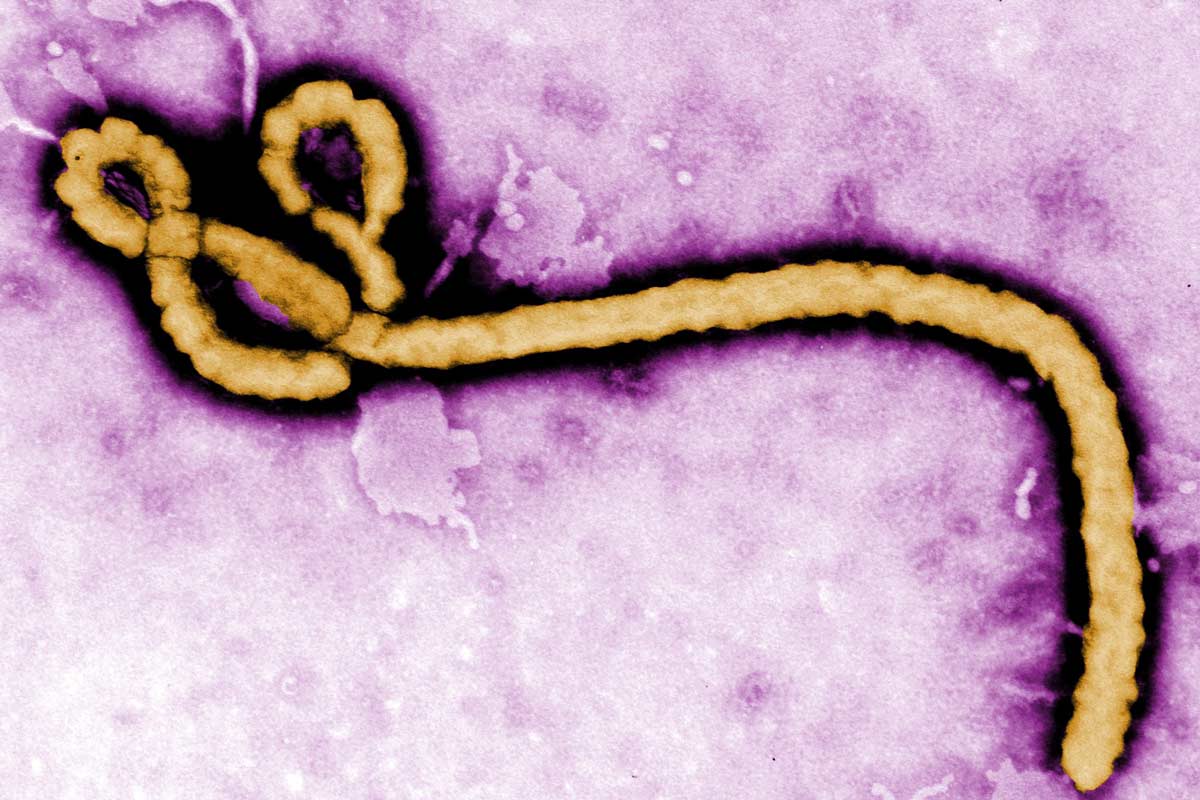

Aurélia Nguyen: Indeed, the current COVID-19 pandemic is something that is quite unprecedented from global health and economic perspectives. We from a Gavi perspective have been working for the last 20 years in developing countries making sure that we are able to provide routine immunisation but also helping to respond to outbreaks of other diseases like yellow fever, measles, meningitis, most recently Ebola, but the current COVID pandemic is on quite a different scale.

Daniel Levine: What has it told us so far about our preparedness to contend with such an outbreak?

Aurélia Nguyen: Our preparedness to contend with this outbreak has been shown to fall quite short of what will be required to make sure that the disease is effectively contained and therefore having the least amount of mortality as well as the knock-on impact to the economy.

In the past there have been realisations during various outbreaks that we need to focus more on global health security, but it’s not in the middle of an outbreak that one starts to prepare; it needs to be done constantly and particularly outside of an outbreak to have health systems being strengthened, have countries have good plans in place and test those plans in place, so we are certainly in catch-up mode here.

Daniel Levine: If listeners think of Gavi, I suspect they think of it as this public/private health organisation that focuses on getting immunisations to poorer nations. What does Gavi do, what’s its role in a pandemic like this?

Aurélia Nguyen: Indeed, Gavi has been in existence for about 20 years and we have focussed our work by pooling donor resources to help countries that have the weakest health systems be able to introduce life-saving vaccines. We’ve done this very much in collaboration with the countries in terms of identifying what their vaccine needs are and then being able to support the introduction of the different vaccines.

We, like the rest of the world, in Gavi, have been looking at the incredible progression of the pandemic, we have taken a look to see how can we leverage the track record that we have in rolling out vaccines and supporting vaccine development and apply it to this situation for COVID-19.

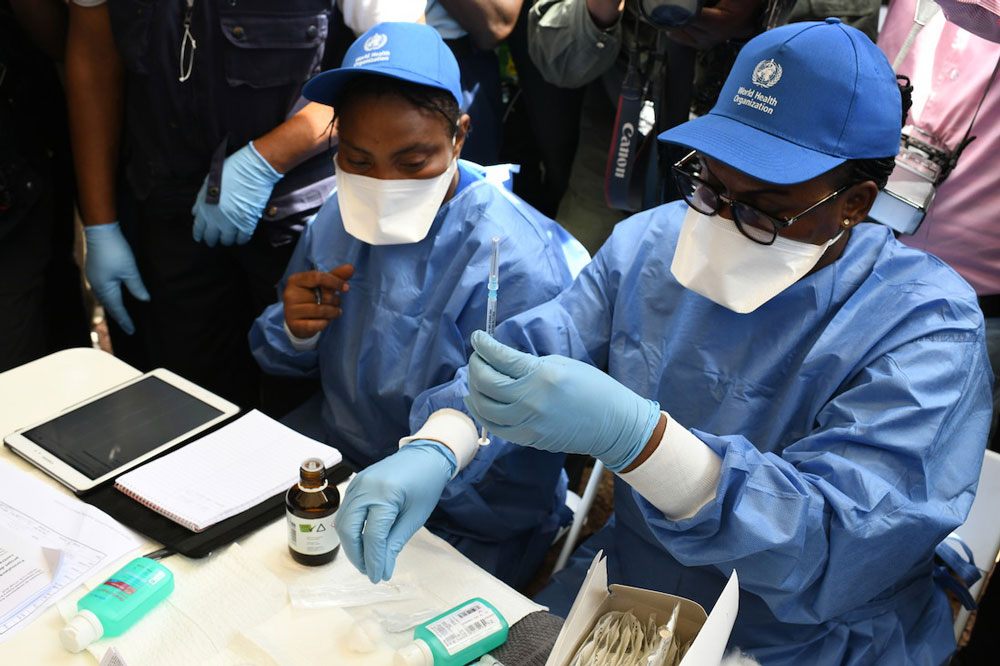

First and foremost, we’ve looked at the countries that we support. COVID-19 cases are starting to emerge more and more in the developing countries. We likely know that the disease is there, it may be just not being identified quite as quickly as it has been in other countries. So, we’ve helped countries look at how they can prioritise some of the support and funding they get from Gavi to help address some of their preparedness.

But we are also going to be very active in the vaccine development, so looking at using some of our innovative financing tools, for example to see how we can rapidly have funding available to the development of vaccine candidates. It’s important that as many vaccines as possible can be developed at the moment so that we have the best selection towards a successful vaccine that will be safe and efficacious.

We are also very heavily involved in terms of how do we think about making sure that when a vaccine does come to light that’s going to help prevent COVID-19, how do we think about making sure that the vaccine is available to those who need it and not necessarily to those who can pay the highest price for it and how do we make sure that there is enough vaccine made for all of those who need it and not just a small subset of people who have taken specific rights towards the vaccine.

Then further down the line from a Gavi perspective, we are supporting the vaccination of about 50% of the world’s first cohort, so we are thinking how we can use all of the systems that we have in place for delivering other vaccines today to help deliver COVID vaccines and make sure that we have a very rapid deployment to the vaccine when it’s made available.

Daniel Levine: The focus today has been to slow the spread of the virus - we have seen the use of a number of practices intending to do that. How critical will the development of a vaccine be to ultimately combating it?

Aurélia Nguyen: It’s very difficult right now for us to assess the trajectory of the outbreak. From Gavi’s perspective, essentially, we are seeing a race against time. The sooner that we are able collectively to identify a good vaccine, produce it, scale it up to produce large amounts of doses start to deploy it, the better chance we will have to be able to potentially have a role in containing the outbreak and then certainly being able to have a vaccine to prevent future outbreaks as is likely to be the case.

Daniel Levine: The current pandemic, as you mentioned, is hitting developed countries right now but it is in Africa, too. How well prepared is Africa to respond to the virus?

Aurélia Nguyen: As I was mentioning before, indeed we are starting to see cases in Africa at the moment. I think a worry is that perhaps we’re only picking up a small number of cases because countries may have weaker capacity to detect. So, the numbers of cases that we are seeing are actually far below what is actually happening in reality.

But the countries that Gavi is supporting are the weakest countries from the perspective of their health systems and so the risk that their health systems become overwhelmed is quite high. Here I think this is where the urgency is in trying to get those health systems as prepared as they can be and then making sure that we can provide support to the countries as they deal with increased cases.

Daniel Levine: Is there any modelling to suggest how the pandemic may progress there or how the response might vary?

Aurélia Nguyen: I think there has been a little bit of modelling done through various groups and modelling a little bit the trajectory that happened in China or in Italy. As in many cases, it really relies heavily on how effective measures like social distancing are done and whether there’s an ability to have testing done. It’s hard to predict at this stage but I think we need to be able to be prepared to react to a high amount of cases.

Daniel Levine: Is there any particular challenge to developing a vaccine for COVID-19 or coronavirus more broadly?

Aurélia Nguyen: From the perspective of the development of the COVID-19 vaccine, we have some helpful experience that we’ve learnt through previous pandemics, SARS, H1N1 and the like.

We also I think need to take an approach in terms of utilising a broad variety of different technologies and different approaches. I think what will be important at this stage is using some of the more traditional technologies that are proven alongside some more innovative ones to be able to see where we’re going to have the highest results.

Of course each come with their pros and cons in terms of having well understood technologies but perhaps with limitations on how quickly they can scale up and innovative technologies that are less well understood and characterised but potentially have an ability to be scaled up much more rapidly, so all of these factors need to be weighed in.

Daniel Levine: Well, given that, what thought should be given to what it would take to manufacture a specific vaccine approach?

Aurélia Nguyen: So, a couple of factors for thinking about manufacturing; one is first and foremost we are going to need a large volume of vaccines. I think that’s a fairly safe assumption and so we need to think about what are the numbers of manufacturers, the types of technologies that will enable us to do so.

Secondly, an important factor that I alluded to before is this question of access. How do we make sure that the vaccines that are produced which initially will likely be in short supply versus the very high demand that will be required are allocated in a manner that is in line with the need from a public health perspective and not with other factors like whoever can pay the highest price for them or whichever country it’s in, who has the ability to lock its borders and not allow for vaccines to be exported. So, the manufacturing perspective needs to include scale, a consideration of geography and a consideration of having the right allocation system to have the vaccine go where it is most needed.

Daniel Levine: Vaccine is already in clinical studies in the United States and China; what’s a realistic timeframe for getting one to the public?

Aurélia Nguyen: Very difficult to say because it’s still very early days with the first vaccines entering Phase I clinical trials. I think an estimate that has been widely quoted has been 18 months or so. I think we’ll know a lot more in a month or two.

Daniel Levine: One issue you touched on earlier which is a concern for Gavi is equitable access. Once a vaccine is developed, how would you expect it to be distributed and made available?

Aurélia Nguyen: This is where I think there is great need for political leadership across countries and agreement between countries to abide by a principle of equitable access. This is where the leadership of the G7 and the G20 and other countries that are very heavily implicated need to come through, so that among all of the different countries, among the vaccine developers and the manufacturers there can be an agreement and a sign on to a principle of allocation based on need.

I think it’s going to take an effort of tremendous political will and of trust and of transparency, perhaps one unlike any seen before, so that we can make sure that we address this as a global community and not as national or private entities because ultimately, given the scale of the pandemic, no one single country is going to be able to protect itself and it will need a global level of cooperation.

Daniel Levine: And is the challenge beyond a financial one? Are there issues in poor countries of distributing vaccines because of supply chain, because of health systems, because of language barriers or trust?

Aurélia Nguyen: Absolutely and I think as we can anticipate, the already very weak healthcare systems are going to be tested to their limits and perhaps beyond, so first and foremost the availability of healthcare workers is going to be very, very strongly tested and in certain areas there is already a sheer lack of healthcare workers.

Then even if we do have the vaccine you alluded to, the question of whether populations will respond effectively to the provision of the vaccine; is there enough trust of the government and the government systems? Are they going to have good acceptability of vaccine by local populations? Is there going to be the right sort of community engagement? Be it through language, through the provision of materials that are needing to engage with for example in populations with low levels of literacy. The community engagement perspective is very critical to consider because even with the tools, if it’s not well accepted then it won’t have any effectiveness.

Daniel Levine: I know you were involved somewhat in the development of an Ebola vaccine that was a very different scale of outbreak, but was anything learned from that experience that might be applicable here?

Aurélia Nguyen: The experience that we had for Ebola has very interesting analogies and in a way has taught us quite a lot.

Firstly, I think the ability for the global community to react and coordinate very quickly is absolutely critical. Secondly, having a good dialogue between all of the different parts of the value chain, if you like, of a vaccine development and rollout, is critical from the research and development perspective to those who will engage in manufacturing, to those who are doing the clinical trials, to the regulators and then onwards to funders and those who roll out the vaccine.

What we learnt is really having that dialogue and those actors together around the table being able to work out issues and give their considerations was very helpful.

It was also I think an important learning to be able to understand some of these questions around access. How do we think about what volumes are being produced, who are they going to be rolled out to if we are in a situation where we have supply shortages? Indeed the Ebola situation, although it was on a smaller scale given the numbers of countries affected, has I think charted a course for a level of coordination that is proving very critical right now within the COVID-19 outbreak.

Daniel Levine: One problem to our approach to developing a vaccine is that even if successful, it would provide us for protection against that pandemic, not the next pandemic. I think here of ‘flu and the threat a new strain could pose. What is the potential for developing a universal coronavirus vaccine and a universal ‘flu vaccine? Is that ultimately where we need to put efforts once we’re through the current crisis?

Aurélia Nguyen: I think we’re still in the phase where we are learning about the virus and its ability to mutate, so I think these are questions that are on the scientists’ minds, and rightly so.

The experience with the ‘flu, as you point out, is that every year we need to think about what circulating strains are likely to happen and try to target a vaccine against them. The experience with developing a universal ‘flu vaccine has been very difficult, it’s been a long and drawn out effort over many, many years.

There are promising leads at the moment, but still not within immediate reach, so as and when we are able to develop a first generation vaccine against COVID-19 for this strain, I think immediately the question will pose itself but first we need to understand a little bit more about the virus.

Daniel Levine: Aurélia Nguyen, Managing Director for Vaccines and Sustainability for the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunizations – Aurélia, thanks so much for your time today.

Aurélia Nguyen: Thank you, Daniel.