The Ugandan tech start-up helping community health workers do more – and carry less

Meet the app designed to help fix the rural health care access gap.

- 11 January 2024

- 5 min read

- by James Karuga

For more than 15 years, Dorothy Kirunda has worked as a community health worker (CHW) in Kiyindi town in Uganda. For most of that time, the record-keeping part of her job has meant fighting a losing battle to protect bulky, dog-eared patient files from rain and dirt. But more recently, she has travelled lighter, carrying just a handbag containing a smartphone equipped with an app called MobiKlinic.

“I was bothered: how can we unlock basic health care services in the rural last mile areas where 80% of Uganda’s population lives?”

– Ansrew Ddembe, co-founder, MobiKlinic

The mobile app and the frontline worker

The MobiKlinic app stores digital patient records and allows CHWs to virtually consult with medical personnel from the nearest health centres. CHWs also use it to call for ambulances, navigate community medical emergencies, refer patients, and access tutorials that discuss basic diagnostics.

Kirunda, who lives 3km from Makonge Health Centre III in Kiyindi town, the nearest health centre, has witnessed the benefits of the app during medical emergencies. In her village, pregnant women seldom get antenatal care since they often can't afford transportation to the nearest health centres. When they develop complications, Kirunda is called in to deliver first aid and arrange for an ambulance.

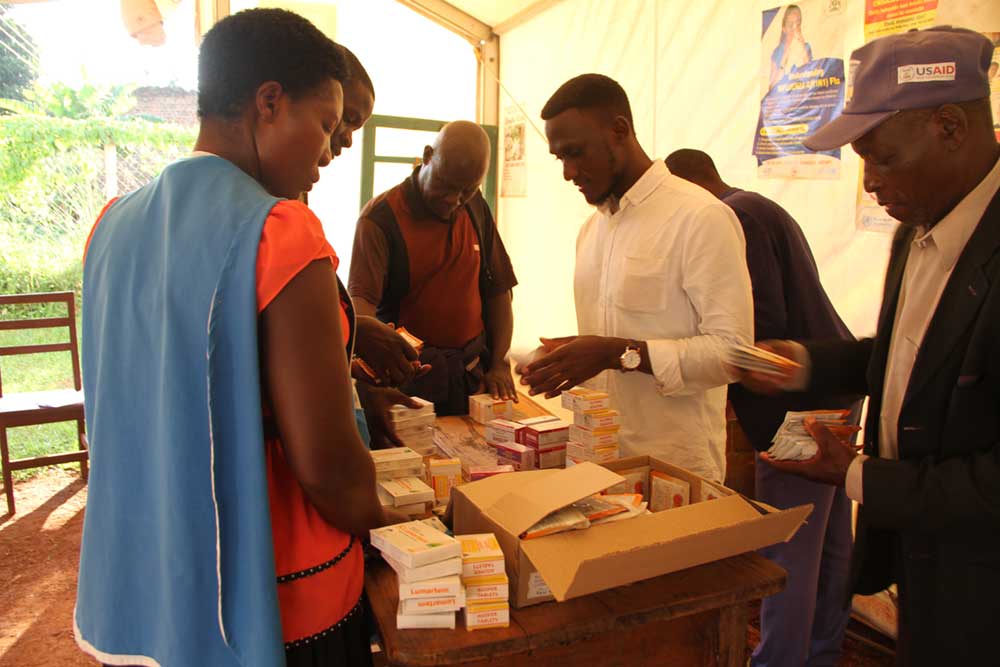

Credit: James Karuga

She recalls once helping a drunk, pregnant woman in the village who had never gone for antenatal care, to deliver twins. As she waited for the ambulance to arrive, she had to deliver the first baby and cut the umbilical cord. She credits the app's guidance and training with the outcome.

"Today those twins are healthy and are three years old. Their mother tells me I am the mother to her children," Kirunda said.

Kiyindi is also a malaria hotspot, lying close to the shores of Lake Victoria. There have been occasions on which Kirunda has needed to administer the first dose of anti-malaria medicine to convulsing children as they waited for an ambulance.

"They [the MobiKlinic team] have trained us to give first aid and respond to medical emergencies, and guide the patients using the app on where to go next [for specialised care]," Kirunda said.

The app also alerts her on nursing mothers in her community whose babies are due for vaccinations, so that she can remind them. It tells her who in her community has not received the full complement of COVID-19 jabs. With the aid of her digital helper, in a month she serves more than 50 people in her village.

The patient

Millie Guttabinji, a grandmother and small fish trader on Lake Victoria, has been struck by the difference in the way the local CHWs work. As a multiple beneficiary of their last-mile health services for years, she now sees them "writing on their" smartphones while taking down medical details, unlike before when they used pen and paper. Consultations are easier, and more orderly now, she says. For her personally, that's a valuable shift. She feels reluctant to visit the local health centre due to long queues and scant privacy, but when a local CHW visits her, she says she is comfortable to open up to them about her ailments.

Have you read?

In the past, she says CHWs have treated her then two-year-old grandson for pneumonia, taking his mucus sample for testing at the local health centre, and days later returning and vaccinating him against tuberculosis. Guttabinji did not seem to know that the CHWs have access to a medic's guidance via the app – she simply appreciates the reliable work CHWs do in her local community, even after vaccinations and treatments are done.

The start-up founder

Growing up in Kampala city and the rural Buikwe district, Andrew Ddembe witnessed the disparities in healthcare access. "In the city, health care was more accessible than in rural areas. In the rural areas when one falls sick, they walk an average of 12km to the nearest health facility, and the population is big and the facilities are overwhelmed," said Ddembe.

Access to doctors in the rural areas was also another challenge he saw. Most doctors prefer working in urban rather than rural areas for financial reasons. In Uganda, one doctor serves about 25,000 patients, which is way below the ratio recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) of one physician for every 1,000 people. "I was bothered: how can we unlock basic health care services in the rural last mile areas where 80% of Uganda's population lives?" said Ddembe.

That motivated him in 2019 to co-found MobiKlinic, a health care start-up based in Kampala that uses digital technology to aid last mile health care.

"We don't work in isolation, we onboard the area (health) facilities. They are our partners to back up the CHWs and strengthen their responses in communities," said Ddembe.

Currently, MobiKlinic is partnered with 10 major rural health centres in Buikwe, Kampala and Rakai districts. The partnership is particularly vital during vaccinations, when the app functionally triangulates information from the roving frontline vaccinators – including CHWs like Kirunda – the patients, the health centres, and the vaccine stores.

Network coverage

"Our ambitious vision is to train 100,000 community health [workers] in the next five years in Uganda and Kenya, and through our e-learning platform, we can scale [up] much faster and train people in different locations at different times to unlock health care access to almost all our population," said Ddembe.

Currently MobiKlinic has a network of 550 CHWs. Two hundred and twenty of them have a smartphone and the app. According to Ddembe, one CHW can reach 200 people. Within Buikwe district, MobiKlinic and the CHWs have served more than 40,000 people so far.

Credit: James Karuga

The positive impact of CHWs' work in communities is reflected in increased vaccination rates at Makonge Health Centre III, according to Rogers Ndayisaba, a nurse who has worked there for 10 years. He's seen evidence of the CHW's successful mobilisation on immunisation rates among both babies and young girls who are eligible for the cervical cancer-blocking HPV jab. "Looking at HPV every week, we are having more than 50 girls getting vaccinated," said Ndayisaba.

Since 2019 the health centre has also seen more and more babies being brought on time – at nine months, according to the national immunisation schedule – for their measles vaccination.

"Before, you would get a child, three years [old], has never been vaccinated for measles, or completely no vaccine, only BCG, which they received at birth. But currently in the community at least every child has received a vaccine," said Ndayisaba.